Attitude, Perceived Risk and Intention to Screen for Prostate Cancer by Adult Men in Kasikeu Sub Location, Makueni County, Kenya

2 Kenya Medical Training College, Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Wote, Makueni, Kenya, Email: gkishoyian@gmail.com

Citation: Kinyao M, et al. Attitude, Perceived Risk and Intention to Screen for Prostate Cancer by Adult Men in Kasikeu Sub Location, Makueni County, Kenya. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2018;8:125-132

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Prostate cancer is increasingly becoming one of the most significant health problems facing Kenyan men and the commonest cause of cancer related death in men globally. Though increased survival rates occur when the diagnosis is done early, the disease is typically detected at a more advanced stage while participation in prostate cancer screening is extremely low. In addition, due to the aging population and population growth, the expected numbers will increase in forthcoming years. Thus, prevention and early detection has immense public health importance. Objective: This study assessed the attitude, perceived risk and intention to screen for prostate cancer by adult men in Kenya. Method: This study was conducted to identify factors associated with intention to be tested for prostate cancer risk among adult men in Kasikeu Sub location, Makueni County, Kenya. An analytical cross-sectional study design using quantitative methods was used. This was achieved through the use of Thomas Jefferson University Prostate Cancer Screening Survey questionnaire using face to face interviews. A sample of 155 men participated in the study and was selected using random selection. Screening for prostate specific antigen (PSA) within the next six months was done and explanatory variables namely attitude, social influence and perceived risk determine. Results: The sample population was aged between 25 to 94 years of age (mean 49.8, SD 16.7). The results indicated that all the men had heard of prostate cancer, but only 3.1% of the men had knowledge (causes and treatment); 2.4% had tested for prostate cancer, and 43.6 percent of the men intended to be tested in the next six months. There was no significant association between demographic factors such as marital status, religion, education level and screening intent (p>0.05). Variables that were significantly associated with intent to screen for cancer were attitude, social influence and perceived risk (p<0.05). Conclusion: There is need for increase health strategies to increase prostate cancer awareness, screening rates which are culturally sensitive and geared toward those living in rural areas with low education levels. In addition, health education should be geared toward modifying men’s attitudes about PSA screening and target socially influential people in their lives especially the family. Recommendations: Qualitative studies could provide a more in depth understanding of perceived barriers to prostate cancer screening. This may provide health care professionals with the information they need to implement strategies to address these barriers, in order to increase prostate cancer screening in Kenyan men and ultimately decrease the rate of mortality from prostate cancer.

Keywords

Attitude; Perceived risk; Prostate cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common malignancy occurring in men and the second most common of all diagnosed cancers. The cancer represents the sixth leading cause of cancer death worldwide with 1,111,700 new cases of prostate cancer diagnosed and 307,500 deaths in 2012. [1] Approximately 70% of the cases occur in developed countries and regions of Australia, New Zealand and America. [2] In Africa, prostate cancer is the leading cancer in both occurrence and the number of deaths. [3] The incidence of prostate cancer is relatively high in South Africa while statistics from Ghana indicate that disease is the second most common cancer among men after liver cancer with an incidence of more than 200 cases per 100,000 of the population per year. [4]

For reasons that remain unclear, African men have the highest rate of incidence for prostate cancer in the world. [5] Moreover, the prostate cancer mortality rate for African American men is twice that of Caucasian men in the United States. As per WHO [1] data, the incidence rate of prostate cancer is 147.8 per 100,000 populations globally, in Africa 17.5 per 100,000 people, East Africa 14.5 per 100,000 people. Uganda had the highest incidence of prostate cancer, 38 per 100,000, with Kenya having 16.6 per 100,000 and a prevalence rate of 17.3%. WHO [1] estimates the current mortality rate for prostate cancer at 22.3 per 100,000 population globally, Africa at 12.5 per 100,000 people in the population and 11.7 per 100,000 people in East Africa. The mortality rate for prostate cancer in Kenya stands at 6.7 per 100,000 people in the population. [1] More so prostate cancer represents 73% of all male reproductive system cancers in Kenya (NCR, 2012).

According to WHO, [1] trends in prostate cancer differ between developed countries and developing countries. These differences are reflected in the incidence and death rates due to prostate cancer. In developed countries the numbers of prostate cancer cases are more as compared to the number in developing countries. The morbidity and mortality rate in developed countries is lower compared to developing countries. There is a decrease in both prevalence (3.6% per year) and mortality (3.4% per year) in USA (CDC, 2013). The prostate cancer in Africa is associated with higher mortality compared to other regions of the world. This pattern is largely due to limited availability of screening and early detection. [1]

According to Wanyagah, [6] 87.5% of Men in Kenya tend to be diagnosed when the cancer is at an advanced stage, which has been posited as a key factor contributing to the disparity in prostate cancer mortality. Prostate cancer incidence rate is 147.8 per 100,000 population globally, Africa 17.5 per 100,000, and Kenya 16.6 per 100,000 population. [1] Mortality rate stands at 22.2 per 100,000 populations globally, Africa 12.5 and Kenya 6.7 per 100,000 population. [1] Although prostate cancer screening remains controversial, it is currently the only method recognized to control prostate cancer disease through early detection.

There is evidence that prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening can detect early stage prostate cancer (Agency for Healthcare Research, 2002), and it is recommended that men at high risk, based on race and family history, should begin early detection with PSA blood test and digital rectal exam (DRE) at 45 years of age, and those at higher risk (having more than one first degree relative who had cancer at an early stage) to start at 40 years of age (American Cancer Society, 2014). Additionally, the American Urological Association (2013) recommended that African American men with multiple first degree relatives diagnosed with prostate cancer begin testing at 40 years of age and those between 55-69 years make screening a routine. Despite these recommended guidelines, there is evidence that African American are less likely to participate in prostate cancer screening services as a method of early detection.

Current statistics on prostate cancer screening show African American men at 50% [7] with Nigeria 4.5% [8] and Kenya 11%. [6] The excessive mortality rates from prostate cancer continue to be a major public health concern. [1] One theory related to the disparity in deaths from prostate cancer is based on prostate cancer screening rates, which could be linked to screening behavior. Poor adherence to screening guidelines raises the question of whether or not there are patterns in knowledge and beliefs toward prostate cancer screening within a subculture that hinder screening.

Subjects and Methods

The study was a multi stage cross-sectional design that examined the relationship and strength of between socio-cultural variables related to attitudes, beliefs and perception with the intent to participate in prostate cancer screening among adult men. The data was collected using a structured questionnaire which was administered by principal investigator with assistance from research assistants

Sampling technique and sample size

Sampling technique: This was a multistage sampling. The area under study consisted of 37 villages. Of these 30% was calculated according to WHO criteria translating to 11 (eleven) villages that participated in the study. Proportion to sample size was used depending on the number of household per village and respondents were selected randomly by use of table of random numbers bringing the actual sample size to 60 males aged 25 yrs and above were selected for the study. Demographic factors (age, marital status and religion) were also examined for relationship with intention to screen. In addition, socioeconomic factor (education level) of the respondents was examined for its association with the men’s preferred source of information.

Sample size: For this study the formula used to determine the sample size was Fisher’s et al. The formula is as follows:

n=Z2PQ/d2

where, n=desired sample size, Z=standard deviation at a confidence level of 95% which is 1.96 and P=proportion of the population with characteristics of interest. Proportion of men tested for prostate cancer=11%=0.11. On substitution, P=0.11, Q=1-0.11=0.89 and D=maximum degree of error when the confidence interval is 95%=0.05, the n=1.962 × 0.11 × 0.89/0.052, the sample size was 150.

Data analysis

Data collected from respondents was transferred to a statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS), version 20. Data checking and cleaning methods included examining the ranges of the respondents for each of the individual variables via frequency distributions, evaluation of each missing data value for possible oversight upon entry, normality, frequencies, descriptive and outliers using SPSS. Missing data was addressed through list wise deletion. This method of handling missing data consisted of excluding cases from any calculations involving variables that had missing data. The fisher test of skewness was used to assess whether or not the continuous data were normally distributed or not. Means and standards deviations were used for summarizing the categorical variables (e.g. age,) and counts and proportions were used to summarize the categorical variables (e.g. marital status, educational level). Decisions for the statistical significance of the findings were made using an alpha level of 0.05.

Results

The socio-demographics and prostate cancer-related characteristics of the respondents who participated in the study are shown in Table 1.

| Age of the respondents | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 25-38 years | 46 | 29.5 |

| 39-46 years | 35 | 22.6 |

| 47-68years | 74 | 47.9 |

| 155 | 100 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 15 | 9.8 |

| Married | 131 | 84.5 |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.7 |

| Separated | 3 | 1.9 |

| Widowed | 5 | 3.1 |

| 155 | 100 | |

| Religion status | ||

| Catholic | 84 | 54.0 |

| Protestant | 62 | 40.0 |

| Muslim | 1 | 0.2 |

| Traditional | 8 | 5.8 |

| 155 | 100 | |

| Education level | ||

| No Formal Education | 38 | 24.5 |

| Primary Level | 60 | 38.8 |

| Secondary Level | 47 | 30.2 |

| Tertially | 10 | 6.4 |

| 155 | 100 | |

| Prostate cancer screening | ||

| Yes | 4 | 2.4 |

| No | 151 | 97.6 |

| 155 | 100 | |

| Intention to screen in 6 months | ||

| Yes | 68 | 43.6 |

| No | 87 | 56.4 |

| 155 | 100 | |

| Risk of getting prostate cancer | ||

| Yes | 99 | 63.7 |

| No | 56 | 36.3 |

| 155 | 100 | |

Table 1: Socio-demographics and prostate cancer-related characteristics. Age of the respondents

The results in Table 1 shows a total of 155 respondents who participated in the study. The average age was 48.9 years (SD=16.7, min=25 max=68). Majority of those that participated in the study, 47.9% (74) were in the age range between 49-68 years, 29.6% (46) 25-38 years while 22.6% (35) in the range 39-46years as shown in Table 1. On marital status, 131 (84.5%), 15 (9.8%), 5 (3.1%), 3 (1.9%) and 1 (0.7%) were married, single, widowed, separated and divorced respectively. On religious status, 84 (54.0%) were Catholics, 62 (40.0%) protestants, 1 (0.2%) Muslims while 8 (5.8%) were traditionalist. According to educational level, 38 (24.5%) had no formal education while 60 (38.8%), 47 (30.2%) and 10 (6.4%) had reached primary (class 1-8), secondary (form 1-4) and tertiary (certificate, diploma and degree) respectively. On whether they have been screened for prostate cancer, 4 (2.4%) and 151 (97.6%) said yes and no in that order. Similarly when asked whether they had the intention of being screen for prostate cancer in six (6) months, 68 (43.6%) and 87 (56.4%) said yes and no respectively. However, when ask whether they are at risk of having prostate cancer, 99 (63.7%) and 56 (36.3%) said yes and no.

Attitude and belief on prostate cancer

The Attitude construct on prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening fatalism, fear/apprehension and perceived benefits, the study found that fatalism score was 3.8 (SD 0.69), which indicated that this sample held relatively strong fatalistic beliefs related to prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening [Table 2].

| I belief it is likely I will get prostate cancer at some time in the future |

| If I am meant to get prostate cancer, I will get it no matter what I do |

|  A man should go for screening once a year |

| Early screening for prostate cancer is likely to increase chances of living a healthier life |

| I think the benefits of prostate cancer screening outweigh any difficulty I might have in going through the tests |

| I want to do what members of my immediate family think I should do about prostate screening |

| I think prostate screening would be painful |

| If I have prostate cancer, I might not know about it early |

| (Being screened for prostate cancer is likely to increase my chances of living a longer life |

| I believe that going through prostate screening would help me to be healthy |

Table 2: Construct used by respondents on attitudes and beliefs on prostate cancer.

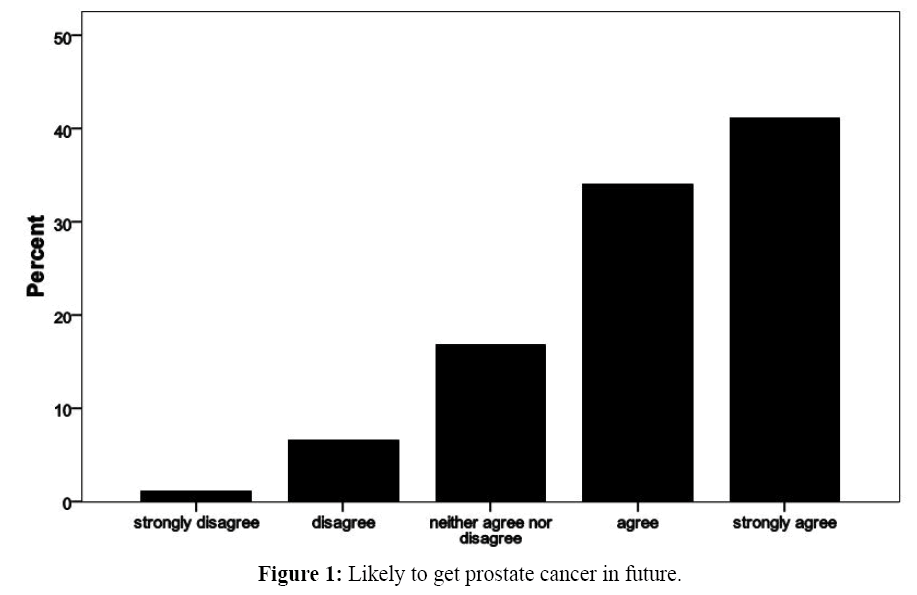

Similarly as shown in Figure 1, the respondent statement on the construct that ‘I believe it is likely I will get prostate cancer at some time in the future’ showed that majority of the men agreed with the statement with few believing on the contrary.

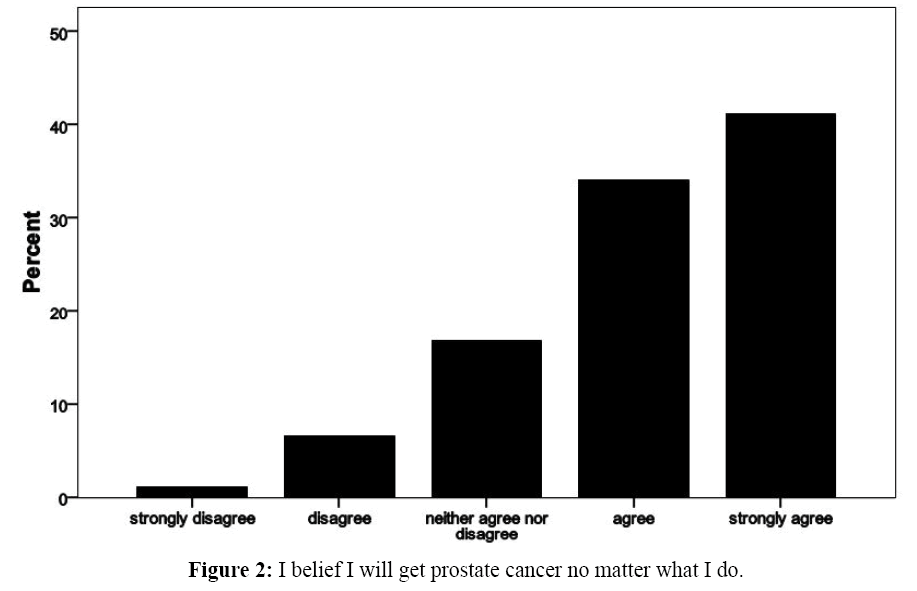

In addition as describe in Figure 2, majority of the respondents agreed that they will get prostate cancer no matter what they do with few disagreeing.

Fear and apprehension

On the respondent response on the construct, ‘I think prostate screening would be painful’ and if I have prostate cancer, I might not know about it early. The Fear/Apprehension mean score was 3.2 (SD 1.3), which indicated a high degree of fear/ apprehension associated with prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening.

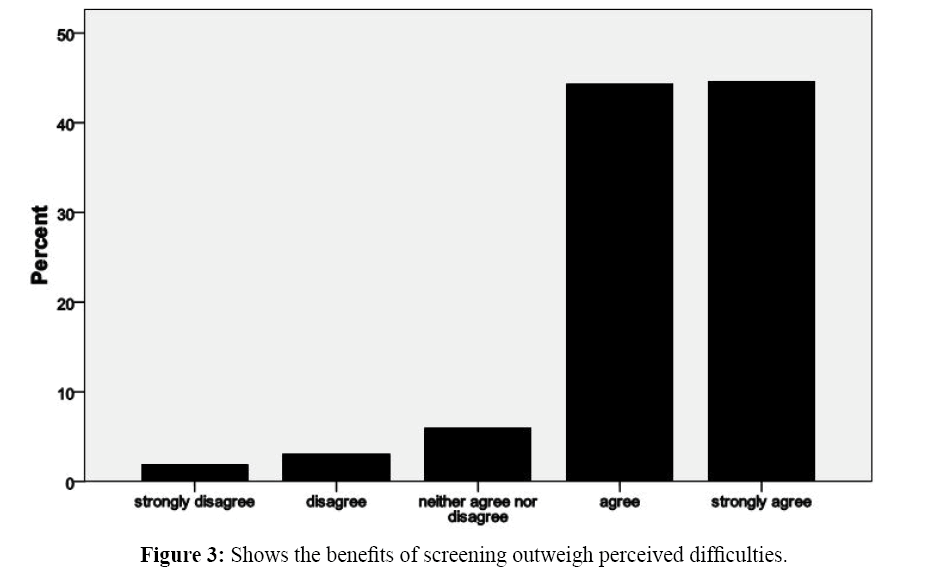

The Perceived Benefits of Screening mean score was 4.02 (SD .0.64), which represented strong beliefs in the benefits of screening among the respondents with majority agreeing that the benefits of screening outweigh any difficulties they might encounter in screening as described in Figure 3.

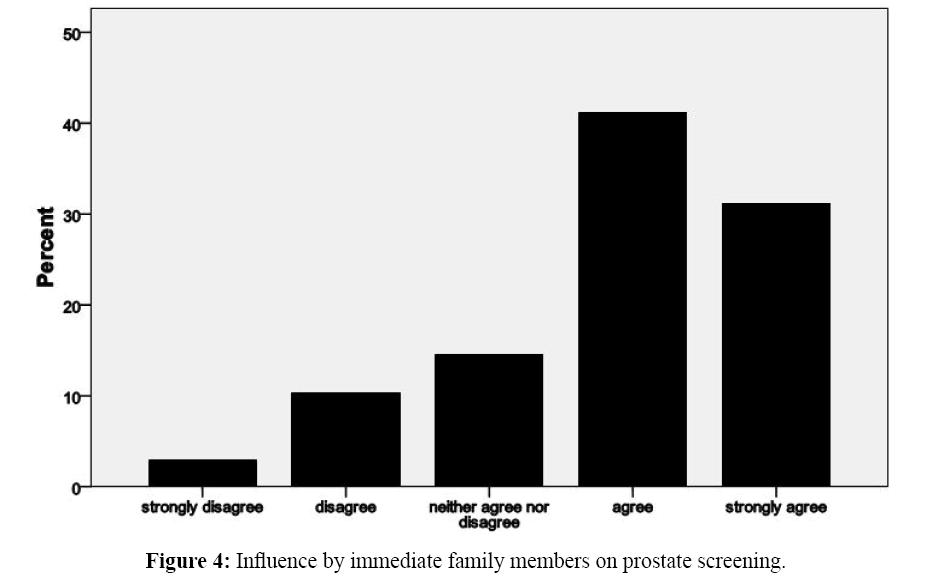

Similarly, on subjective norm construct as shown in figure 4, social influence mean score was 3.8 (SD 1.0), which represented the level of influence family members had on prostate cancer screening among this sample. From the statement that ‘I want to do what members of my immediate family think I should do about prostate screening’ had a higher impact of over 70% that most men would depend on family members for advice on prostate cancer screening.

Knowledge and awareness of prostate cancer

A year prior to the survey, a government minister had come openly to declare his prostate cancer status and people had heard him from the various sources. Since the study showed that very few (3.1%) were knowledgeable about the disease, the study focused on awareness or what they had heard on the disease. All the men interviewed were aware of prostate cancer because they had heard about it from different sources.

Sources of information about prostate cancer screening (DRE and PSA)

Men who reported having heard of prostate cancer were asked what had been their sources of information about the disease. Note the data is cumulative as one person could have heard information from different sources. However, 44.3% of the respondents heard about it from the radio and only 5.5% first heard from health facility or health staff or through the media (newspaper, magazines, television,). The radio was the greatest source of information. In addition, 51% of the men obtained information from one source, 36.6% had information from two sources while 11.4% had information from three or more sources.

Preferred source of information on prostate cancer screening and education level

Preferred Sources of information on prostate cancer was measured using a number of sources as shown in Table 3. The respondents were asked their preferred source of information on prostate cancer. The sources were newspapers, television, radio, website, community health workers, hospital, relatives and any other source. The preference of source of information differed with education levels p<0.05). There is a statistically significant association between level of education and preferred source of information on prostate cancer. This shows that there is a relationship between level of education and the preferred source of information.

| Education Level | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No formal education | Primary level | Secondary Level | Tertiary | |||

|    Preferred Source | Newspaper | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 0% | 0% | 1.6% | 11% | 1.2% | ||

| Television | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| .0% | .0% | .8% | .0% | 0.1% | ||

| Radio | 25 | 36 | 29 | 4 | 94 | |

| 65.7% | 61.3% | 59.1% | 46.2% | 60.9% | ||

| Website | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| .0% | .0% | .8% | 19.2% | 1.4% | ||

| Community Health Worker (CHW) | 8 | 18 | 15 | 2 | 43 | |

| 21.3% | 30.1% | 30.7% | 23.1% | 28.2% | ||

| hospital | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| 7.8% | 4.9% | 4.7% | 3.8% | 5.5% | ||

| family /friends | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 2.6% | 1.2% | .0% | 0% | 1.0% | ||

| other sources | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| 2.6% | 1.2% | 2.4% | 3.8% | 1.7% | ||

| Total | 38 | 59 | 49 | 9 | 155 | |

| 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

Table 3: Preferred source of information and education level of men.

Associations between attitudes, social influence and perception with prostate cancer screening intent

The independent variables of attitudes included fatalistic perceptions of prostate cancer, fears associated with prostate cancer screening and screening outcomes and the perceived benefits of prostate cancer screening. Of the three independent variables, only fear had a statistically significant association (p<0.05) with prostate cancer screening intent.

Discussion

In the current study, the distribution of prostate cancer beliefs suggests that participants held relatively strong fatalistic attitudes toward prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening mean=3.8, SD=0.69). ‘If I am meant to get prostate cancer, I will get it no matter what I do’ These findings were inconsistent with qualitative studies where cancer fatalism, as a barrier to prostate cancer screening was a predominant theme. [9,10] In addition, the study found that there was no significant correlation between fatalistic factors and intent to screen. This could be attributed to the use of one question to assess fatalism and prostate cancer beliefs, and probably a score of more statements on fatalism could have been used.

Approximately half of men in the study population reported intention to be tested for prostate cancer risk when such testing becomes available. This is in contrast to studies done in developed countries where overwhelming majority of men reported a high level of intention to be tested for prostate cancer risk when such testing becomes available. These finding are similar to results reported in several studies conducted among patients with a family history of cancer and in the general population. It is also consistent with the results of studies in which men who were family members of prostate cancer patients have been asked about their intention to be tested for prostate cancer risk. [11-13]

In the same study, the relationship of the attitude of fear/ apprehension with prostate cancer screening intent was examined and was statistically significant (p<0.05.) This observation is consistent with that of Woods et al. [14] who examined selfreported barriers to prostate cancer screening, and found out that the majority of respondents in the study reported fear-related barriers to obtaining prostate cancer screening. Fear associated with prostate cancer was also a significant finding by Spain et al. [15] study.

The theoretical linking of perceived benefits has been included in several health behavior models as an attitudinal construct of expected consequences of an action that has been found to be associated intentions to engage in specific behaviors. [11] As a measure of attitude, perceived benefits of prostate cancer screening was univariately associated at a statistically significant level with prostate cancer screening intent as observed by Kenerso. [16] Also, these findings were consistent with a study conducted by Talcott et al. [16] who found that African American men believed the benefits of prostate cancer screening outweighed perceived barriers to screening.

In an earlier study, Plowden et al. [7] using the Health Belief Model as a framework of their study, found that in their sample African American men reported that they perceived the benefit of going for screening at a similar level as Caucasian men, though prostate cancer screening participation rates of African American men were much less than those of Caucasian. The current findings contrast with the above studies because there was no statistical significant association between perceived benefits of prostate screening and intention to screen. This could be attributed to the small percentage of men who were screened [17].

On social influence, as a measure of social norms and to assess the level of influence, family members have the decision to engage in prostate cancer screening. In the present study, family influence have a significant positive correlation with prostate cancer screening intent (p<0.05). Several studies have observed the important role of familial social support in influencing decision-making related to prostate cancer screening among African-American men. [14,16,18] In addition, a study by Odedina et al., [19] showed that social influence was associated with prostate cancer screening intent among African American men. The current study assessed social influence and observed that other family members were perceived as actively putting forth their views related to prostate cancer screening. Also, the findings observed that prostate cancer screening intent among the subjects is governed by social interactions that are culturally influence.

Though this study was not able to associate knowledge with intent to screen for cancer due to the very small number of men n=5(3.1%) who were knowledgeable of prostate cancer, the study objective was achieved. Although African American men have generally been found to have lower levels of prostate cancer and screening knowledge when compared to Caucasians, [17,20] there is little evidence to support whether or not it contributes in a significant way to screening behavior. Kenerson [16] found no statistical significance between knowledge and prostate cancer screening intent. This is in contrast to widely held beliefs, particularly among health promoters, that knowledge translates to positive health behaviors.

The study also observed that perceived risk of prostate cancer were significantly associated with prostate cancer screening intent (p<0.05) among the study sample. The measure for risk was yes/no of ‘Do you think you are at risk of developing prostate cancer. The results were similar to those found by kenesson [16] who observed statistically significant relationship between the belief that family history of prostate cancer increases one’s risk for developing prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening intent. Also, a study by Weinrich’s [18] demonstrated that African American men with a strong family history of prostate cancer had significantly lower screening rates than Caucasians and African American who did not have a strong family history of prostate cancer. On the other hand, Bloom et al. [21] found that African American men with a self-reported family history of prostate cancer did not perceive their prostate cancer risk to be any higher than men without a family history.

Demographic variables were also examined for their contribution to prostate cancer screening intent. The association between being married and prostate cancer screening intent has been found in studies of African American men and prostate cancer. [22,23] However, there were no statistically significant differences between marital status and prostate cancer screening intent of men in the study. However, the current study did not establish any relationship between age and prostate cancer screening intent (p>0.05). This is inconsistent with Men in the study by Kenerson [16] who found that men who were 50 or more years of age were significantly less likely than younger men to say that they intended to be tested. Reasons for this lack of consistency across studies in the relationship between age and intention to be tested are not clear.

Levels of education and income have also been associated with increased level of prostate cancer screening. [20] They examined the roles of education, race, and screening status in men’s beliefs and knowledge about prostate cancer. They found that education, not race, was associated with prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening knowledge However, the study did not demonstrate any statistically significant association between education, and the intent to screen for prostate cancer. This could be due to the low percentage of men in my study who have gone beyond primary level. However, there was a significant difference between education and preferred source of information (p<=0.05).

This study conclude that the theory of planned behavior used in this study proved appropriate to examine conceptual associations between prostate cancer and prostate cancer screening attitude, health related beliefs, social influence and the intent to participate in prostate cancer screening though it has not been extensively applied to the examination of prostate cancer screening behaviors of Kenyan men. Fear of examinations for prostate cancers, Social influence and perception of risk to prostate cancer was associated with prostate cancer screening intent. The study observed that the decision to go for a prostate cancer screening can be influenced by fear, family members, and perception of risk to prostate cancer and not demographic factors. The family played a significant role on prostate cancer screening intent, which implies that the involvement of close family members influences decision making.

Lastly, prostate cancer and screening education alone may not necessarily prompt men to engage in screening, but requires an understanding of health workers of their attitudes and beliefs about specific health issues. The study recommends that the Theory of Planned Behavior which provided a framework for the examination of socio-cultural factors thought to be associated with the patterns of health behavior needs more studies since only a few of its constructs were applied. The study recommend more studies on behavioral factors contributing to prostate cancer screening including general attitudes, beliefs and social influence. The need to determine barriers for prostate cancer risk among men using a qualitative study in different geographical set ups. The results can be used by policy makers to develop health information massages to create awareness to the public on prostate cancer screening. Ministry of health at both national and county level should involve family members in prostate cancer screening campaigns through public forum at community level and the local media.

Strength of the Study

This study is one of the few studies done to determine the attitude, perceived risk and intention to screen for prostate cancer by adult men in Makueni County, Kenya.

Limitation of study

The findings obtained could not be generalized because the sample size and the study recruited a small number of respondents and only those that were present during data collection and consented were included in the study. However we were able to achieve the objectives of the study on the attitude, perceived risk and intention to screen for prostate cancer by adult men.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MK designed the study, collected and analyzed data and drafted the manuscript. MK and GK designed the study, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Great Lakes University of Kisumu (GLUK) Research and Ethical Committee Ethics Review Committee.

Ethical consent from the participate

The participants were fully informed fully Informed about the purpose of the study and that the study is voluntary hence they have the option of withdrawing any time without notice. They were also explained that the measures were taken for confidentiality of the outcome of the data. Also, only coded numbers will be used and not names on any presentations or publication.

Consent to publish

Written Informed consent for publication of the results of study was obtained from the respondents on condition their names should be deleted. A copy of the consent form is available in individual file and is available on request.

Availability of data and materials

The data analyzed during the current study is available from the principal investigator on request.

REFERENCES

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. World Health Organization, 2012, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Yeboah BA, Yirenya TD, BaafiDM,Ackumey M. Perceptions and knowledge about prostate cancer and attitudes towards prostate cancer screening among male teachers in the Sunyani Municipality, Ghana. African Journal of Urology. 2017;23: 184-191.

- RebbeckTR, Devesa SS, Chang BL, Bunker CH, Cheng I, Cooney K, et al. Global patterns of prostate cancer incidence, aggressiveness, and mortality in men of African descent. Prostate Cancer. 2013;560-857.

- Mofolo N, Betshu O, Kenna O, Koroma S, Lebeko T,Claassen MN. Knowledge of prostate cancer among males attending a urology clinic, a South African study Springer Plus. 2015;4:67.

- Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, et al. Cancer statistics. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians.2005;55:10-30.

- Wanyangah P. Prostate cancer awareness, knowledge, perception on self-vulnerability and uptake of screening among men in Nairobi County, Kenya. 2014.

- Plowden KO. To screen or not to screen: Factors influencing the decision to participate in prostate cancer screening among urban African American men. Urologic Nursing. 2006;26:477-482.

- Oladimeji O, BidemiYO, Olufisayo JA, Sola AO. Prostate cancer awareness, knowledge, and screening practices among older men in Oyo State, Nigeria. IntCommunity Health Educ. 2010;30:271-286.

- McFall SL. U.S. men discussing prostate-specific antigen tests with a physician. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4:433-436.

- Forrester-Anderson IT. Prostate cancer screening perceptions, knowledge and behaviors among African American men: Focus group findings. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16:22-30.

- Bratt O, Garmo H, Adolfsson J, Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Lambe M, et al. Effects of prostate-specific antigen testing on familial prostate cancer risk estimates. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1336-1343.

- Diefenbach MA, Davis SN. Pros and cons of prostate cancer screening: associations with screening knowledge and attitudes among urban African American men, Journal of theNational Medical Association. 2010;102:174-182.

- Miller SM, Diefenbach MA, KruusLK, Watkins-Bruner D, Hanks GE, Engstrom PF.Psychological and screening profiles of first-degree relatives of prostate cancer patients.J Behav Med. 2001;24:247-258.

- Woods DV, Montgomery SB, Herring P, Gardner RW, Stokols D. Social ecological predictors of prostate-specific antigen blood test and digital rectal examination in black American men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:492-504.

- Spain P, Carpenter WR, Talcott JA, Clark JA, Kyung Do Y, Hamilton RJ, et al. Perceived family history risk and symptomatic diagnosis of prostate cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:2180-2187.

- Kenerson D. Use of theory of planned behavior to assess prostate cancer screening intent among African American men. 2010.

- Talcott JA, Spain P, Clark JA, Carpenter WR, Kyung Do Y, Hamilton RJ, et al. Hidden barriers between knowledge and behavior: The North Carolina prostate cancer screening and treatment experience. Cancer. 2007;109:1599-1606.

- Weinrich SP. Prostate cancer screening in high-risk men: African American hereditary prostate cancer study network. Cancer. 2006;106:796-803.

- Odedina FT, Akinremi TO, Chinegwundoh F, Roberts R, Yu D, Reams RR, et al. Prostate cancer disparities in black men of African descent: a comparative literature review of prostate cancer burden among black men in the United States, Caribbean, United Kingdom, and West Africa. Infectious Agents and Cancer. 2009;38:227-233.

- Winterich JA, Grzywacz JG, Quandt SA, Clark PE, Miller DP, Acuna J, et al. Men's knowledge and beliefs about prostate cancer: Education, race, and screening status. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19:199-203.

- Bloom JR, Stewart SL, Oakley-Girvans I, Banks PJ, Chang S. Family history, perceived risk, and prostate cancer screening among African American men. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2006;15:2167-2173.

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008,†International Journal of Cancer.2010;127:2893-2917.

- Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, RimerBK, Lee N. Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: Results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2003;97:1528-1540.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.