Comparison between Topical Platelet Rich Plasma and Normal Saline Dressing, in Conjunction with Total Contact Casting in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcer–A Randomized Control Trial

Received: 05-Jun-2024, Manuscript No. amhsr-24-134387 ; Editor assigned: 07-Jun-2024, Pre QC No. amhsr-24-134387 (PQ); Reviewed: 24-Jun-2024 QC No. amhsr-24-134387; Revised: 01-Jul-2024, Manuscript No. amhsr-24-134387 (R); Published: 08-Jul-2024

Citation: Das S, et al. Comparison between topical Platelet Rich Plasma and Normal Saline Dressing, in Conjunction with Total Contact Casting in Treatment of Diabetic Foot Ulcer– A Randomized Control Trial. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2024;14:995-1000.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Introduction: Wound care plays an important role in the management of diabetic foot ulcer, which includes cleaning and stimulate a moist wound healing environment. Total-contact cast is widely use as the most effective external technique for off-loading plantar ulcers. This study compares the effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) and normal saline dressing in conjunction with Total-Contact Cast (TCC).

Methods: 36 patients of diabetic foot ulcer was taken and divided in to 2 groups using computer generated randomization into PRP group and NS group with 18 patients in each group. PRP group was given autologous PRP and NS group was given wet dressing with NS; following which TCC was applied in each case for off-loading. Follow up was done every 15 days up to 90 days. In each follow-up measurement and TCC application was done, time to heal and PUSH (Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing) score has been used to measure condition of the wound.

Results: In PRP group the mean wound size 8.28 ± 1.18 and mean PUSH tool total 13.44 ± 0.98 at base line which was gradually decreased and finally at day 90 it was reduced to 0.61 ± 1.20 and 1.89 ± 3.68 respectively. In NS group the mean wound size 8.45 ± 1.13 and mean PUSH tool total 13.50 ± 0.92 at baseline which was gradually decreased and finally at day 90 it was reduced to 1.58 ± 1.55 and 4.61 ± 4.37 respectively. Significant difference was found in both the groups at final evaluation. Compared to the NS group, the PRP group exhibits greater improvement.

Conclusion: Both autologous PRP and NS are effective in treating DFU, when used along with TCC. But PRP therapy is better in reducing healing time and hospital visits.

Keywords

Platelet rich plasma; Normal saline; Total contact casting; Diabetic foot ulcer

Introduction

The metabolic condition known as Type II Diabetes (DM2) is marked by hyperglycemia followed through insulin resistance [1]. Numerous co-morbidities, including peripheral neuropathy, chronic renal failure, stroke, cardiovascular disease and diabetic foot ulcer are linked to type 2 diabetes mellitus [2]. The most common side effect of type 2 DM is Diabetic Foot Ulcers (DFUs), which can result in repeated hospital visits, hospital stays and financial strain for the patients [3]. Poor blood glucose management and high plantar pressure are the primary causes of DFUs, which are defined as full-thickness wounds that penetrate the dermis (the deep vascular and collagenous inner skin layer) and are located below the ankle in diabetic patients [4,5]. Diabetic ulcer present as excruciating ulcers that break down dermal tissue, including the dermis, epidermis and often subcutaneous tissue. The non-healing phenotype of diabetic foot ulceration has been attributed to immune system dysfunction, microbial invasion and epithelial disintegration. 25% of diabetics have a life time risk of developing diabetic foot ulcers, the majority of whom will require amputation within four years of the initial diagnosis [3].

Due to their multi-factorial etiology, these foot ulcers are difficult to treat and place a significant burden on patients, health care systems and society [6]. Prevention is the key to managing diabetic foot wounds [7]. Patient education, regular foot examinations and therapeutic foot wear are essential for preventing DFU [7,8]. Good clinical care entails frequent debridement, off-loading via casting with a walking rod, Total Contact Cast (TCC), orthotic support, moist wound care with various dressing materials like Normal Saline (NS), an antimicrobial agent and alginate; treatment of infection; and revascularization of the ischemic limb [9]. In severe wounds, however, vascular repair or amputation Jul be necessary [10,11].15% of diabetic worldwide will develop Diabetic Foot Ulcers (DFU) at some point in their lives. The amputation of about 28% of them may be necessary [12].The prevalence of DFU globally is 6.3% in the overall population and is expected to rise in the future [13]. In India, the prevalence of diabetic foot ulcers is 4%-5%, which is much lower than what is reported in western countries [14].

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study was conducted at a tertiary care center with a well-equipped research laboratory and other facilities for patient care after obtaining institutional ethical committee approval via AIIMS/Pat/IEC/PGTh/July, 2002, dated 29, September. The (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) CONSORT statement's requirements for reporting randomized controlled trials were followed and the study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design and sample

This is arandomized Clinical trial done in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, All India Institute of Medical Science, Patna. The study population was estimated using statistical formulas and 36 patients were considered in each group based on sample size calculations. Convenient sampling was used to recruit the cases after fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria for a period from October, 2021 to November, 2022. All patients gave their written informed consent. A complete examination of each subject was performed. Between two groups, the patients were randomly assigned. The patients in the first group were given PRP therapy along with TCC; where as the patients in the second groups were given NS dressing along with TCC. In this study, data will be collected, and the outcome will be measured in terms of time to heal and PUSH Tool 3.0. SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 25 software will be used for statistical analysis after the collection of all relevant data.

Study procedure

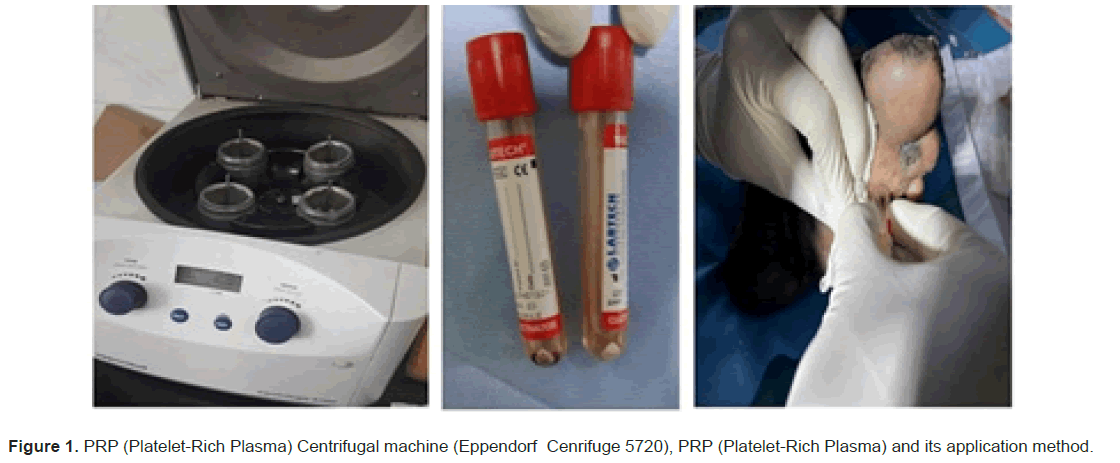

PRP preparation and application: Twenty milliliters of blood, taken from the basilic antecubital veins, were put into vacuumsterilized test tubes together with 3.8 milliliters of sodium citrate to serve as an anticoagulant. Using an Eppendorf Centrifuge 5720, blood samples were centrifuged for 12 minutes at 1,200 revolutions per minute. Three layers of blood were isolated: Red blood cells were found in the bottom layer, platelets and white blood cells were found in the middle thin layer and white blood cells (the buffy coat) were found in the upper layer. The upper and intermediate buffy layers were transferred using an empty sterile tube. In order to facilitate the development of soft pellets (erythrocytes and platelets) at the tube's bottom, the plasma was centrifuged once more for seven minutes at 3,300 rpm; upper two thirds of the platelet poor plasma to be discarded; pellets were homogenized in the lowest third (3 ml) of the plasma to generate the PRP; the PRP was then extracted using a 5 ml syringe [15]. After taking measurements of the wound, proper cleaning and debridement were done. Then freshly prepared autologous PRP was applied to ulcer bed. The wound was covered by dry sterile gauze. After proper covering a total contact cast was applied for offloading (Figure 1).

NS dressing application: Measurements of the wound were taken first. Cleaning and debridement of the wound was done. Then normal saline soaked gauze was applied over ulcer bed. Wound was covered with dry sterile gauze. After proper covering a total contact cast was applied for offloading.

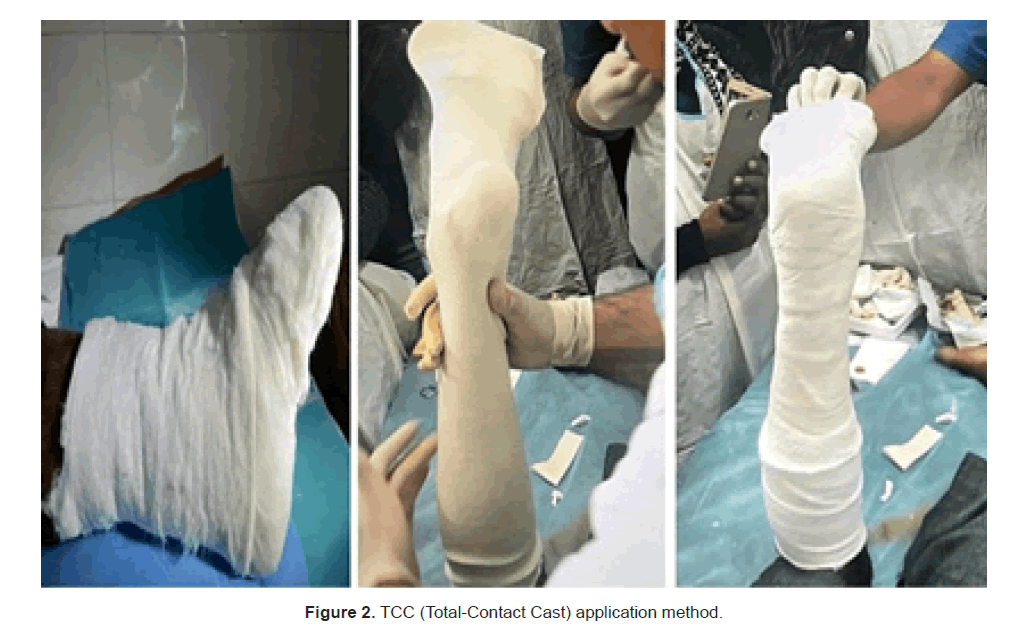

TCC application: Inter digital padding was applied first. Next, the stockinet was put on from the knee to the toes in a way that showed the toes and prevented wrinkles or bunching. The stockinet was covered with cotton padding. Under the medial longitudinal arch, a layer of felt (D-filler) padding measuring 10 mm to 15 mm was positioned. Cut to size, 5 mm silicone strips were put across bony prominences (e.g., medial/lateral malleoli, anterior tibia). Over the cushioning, a plaster of paris cast was put, extending one inch distal to the fibular head from the tips of the toes. To provide optimal contact, the cast was precisely shaped to fit the leg and foot. Patients will be instructed to walk no more than one-third of their normal ambulation (Figure 2).

Follow-up and statistical analysis plan: Data collection (by“t imetoheal”and“PUSHTool3.0”) will be done at baseline and in subsequent, 2 weekly follow-up, upto 3 months. In each followup measurement, debridement and TCC re-application will be done. The data was examined using IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY's SPSS programme (version 23). A significant threshold of P<0.05 was established. To compare qualitative factors, the X2 test was employed, while the Unpaired T-test was utilized to assess quantitative data. The standard deviation of quantitative variables' normal distribution was used to determine the significance level, which was set at p-value 0.05.

Results

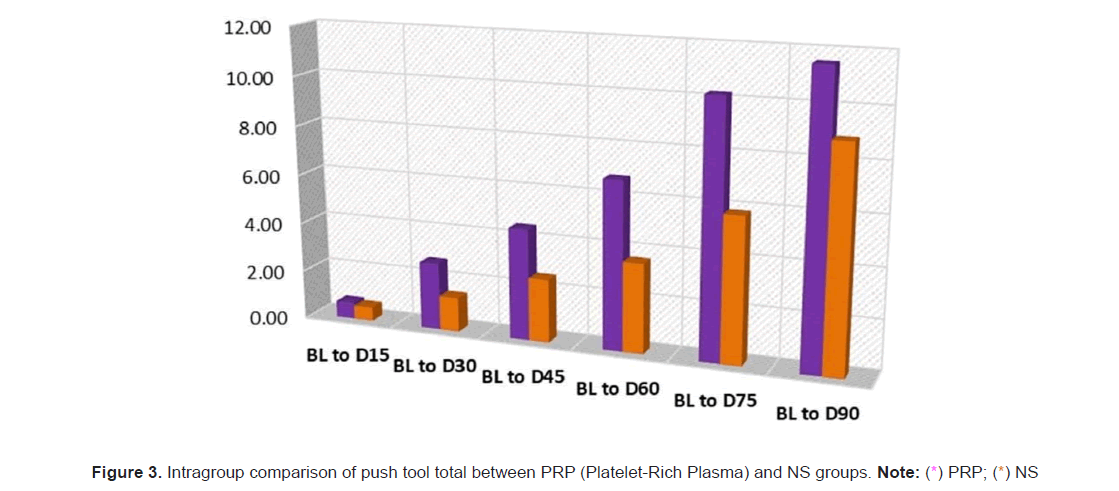

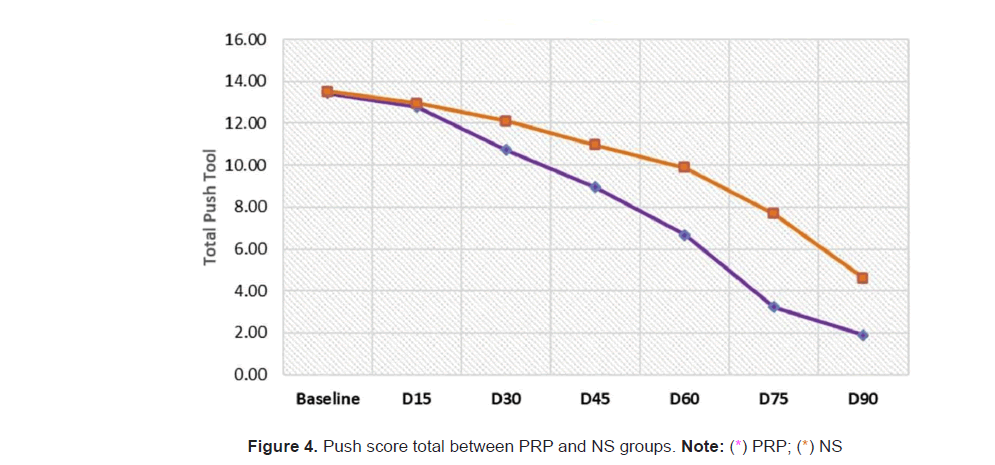

In the PRP group, 11 (61.1%) cases were male and the rest 7 (38.9%) were female; while in the NS group, 10(55.6%) cases were males and the rest 8 (44.4%) were females. Hence, in the study, 21 (58.3%) were males and 15 (41.7%) were females. The proportions of men and women in each group did not differ significantly (p=0.735). Hence, the groups were matched for sex. The left and right sides were involved in equalproportions in both the PRP and NS groups. The mean age of the PRP group was 56.50 ± 4.96 years, while themean age of the NS group was 54.89 ± 4.51 years. No significant difference was found in mean ages betweenthe PRP and NS groups (p = 0.315). The mean BMI of the PRP group was 26.07 ± 3.70 kg/m2, while the mean BMI of the NS group was 25.17 ± 3.28 kg/m2. PRP and NS groups mean BMIs did not differ significantly (p=0.447) (Figure 1). The mean duration of DM of PRP group was 14.22 ± 5.37 years while the mean duration of DM of NS groupwas 11.00 ± 4.39 years. No significant difference was found in mean duration between PRP and NS group (p=0.057). The mean ABI of PRP group was 0.99 ± 0.12 while the mean ABI of NS group was 0.98 ± 0.15. No significant difference was found in mean ABI between PRP and NS group (p=0.811). The mean HbA1c of PRPgroup was 8.57 ± 0.67 while the mean HbA1c of NS group was 8.15 ± 0.52. No significant difference was found in mean HbA1c between PRP and NS group (p=0.53). The mean RBS of PRP group was 217.22 ± 27.78 while the mean HbA1c of NS group was 208.00 ± 23.51. No significant difference was found in mean RBS between PRPand NS group (p=0.290). The mean platelet of PRP group was 258.44 ± 45.30 while the mean platelet of NSgroup was 243.22 ± 42.32. No significant difference was found in mean platelet between PRP and NS group (p=0.305). The mean Albumin of PRP group was 3.77 ± 0.38 while the mean albumin of NS group was 3.64 ± 0.72. No significant difference was found in mean platelet between PRP and NS group (p=0.508). The mean time to heal in PRP group was 11.17 ± 2.73 weeks while the mean time to heal in NS group was 13.78 ± 1.66 weeks. Significant difference was found in mean time to heal between PRP and NS group (Table 1). In PRP group the mean wound size at baseline was 8.28 ± 1.18 which was gradually decreased and finally atday 90 it was reduced to 0.61 ± 1.20. In NS group the mean wound size at baseline was 8.45 ± 1.13 which wasgradually decreased and finally at day 90 it was reduced to 1.58 ± 1.55. The PRP and NS groups showed asignificant difference in mean wound size at day 30 (p=0.001), day 45 (p=0.001), day 60 (p=0.001), day 75(p=0.002) and day 90 (p=0.044) (Table 2). From the baseline to days 15 (p<0.001), 30 (p<0.001), 45 (p<0.001), 60 (p<0.001), 75 (p<0.001) and 90 (p<0.001), the mean change in wound size in the PRP group was shown to be significant. From base line to days 15 (p<0.001), 30 (p<0.001), 45 (p<0.001), 60 (p<0.001), 75 (p<0.001) and 90 (p<0.001),the mean change in wound size was determined to be significant in the NS group (Table 3). In PRP group the mean Push tool total at baseline was 13.44 ± 0.98 which was gradually decreased and finally at day 90 it was reduced to 1.89 ± 3.68. In NS group the mean push tool total at baseline was 13.50 ± 0.92 which was gradually decreased and finally at day 90 it was reduced to 4.61 ± 4.37.Significant difference was found in mean push tool total between PRP and NS groups at day 30 (p=0.015), day 45 (p=0.016), day 60 (p=0.003)and day 75 (p=0.002) (Figure 2). In PRP group the mean change in PUSH tool total was found to be significant from baseline to day 15 (p<0.001), day 30 (p<0.001), day 45 (p<0.001), day60 (p<0.001), day 75 (p<0.001) and day 90 (p<0.001). In NS group the mean change in push tool total was found to be significant from baseline to day15 (p=0.001), day 30(p<0.001), day 45(p<0.001), day 60(p<0.001), day 75(p<0.001) and day 90(p<0.001) (Figures 3 and 4).

| Intervention | Time to heal (weeks) | Unpaired test t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| PRP group | 11.17 | 2.73 | -3.467 | 0.001 |

Table 1: Intergroup comparison of time to heal.

| Wound Size | PRP group | NS group | t-value | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| baseline | 8.28 | 1.18 | 8.45 | 1.13 | -0.44 | 0.665 |

| D15 | 7.7 | 1.17 | 8.19 | 1.28 | -1.19 | 0.243 |

| D30 | 5.92 | 1.58 | 7.76 | 1.46 | -3.62 | 0.001 |

| D45 | 4.43 | 1.75 | 6.4 | 1.4 | -3.73 | 0.001 |

| D60 | 2.83 | 1.78 | 4.86 | 1.38 | -3.82 | 0.001 |

| D75 | 1.32 | 1.79 | 3.24 | 1.6 | -3.4 | 0.002 |

| D90 | 0.61 | 1.2 | 1.58 | 1.55 | -2.1 | 0.044 |

Table 2: Intergroup comparison of wound size.

| Wound Size | PRP group | NS group | t-value | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| baseline | 7.72 | 0.46 | 7.56 | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.312 |

| D15 | 7.39 | 0.5 | 7.5 | 0.51 | -0.66 | 0.516 |

| D30 | 6.83 | 0.62 | 7.39 | 0.5 | -2.96 | 0.006 |

| D45 | 6.22 | 1.7 | 7.22 | 0.43 | -2.42 | 0.021 |

| D60 | 4.89 | 2.42 | 6.67 | 0.69 | -3 | 0.005 |

| D75 | 2.22 | 2.9 | 5.28 | 2.14 | -3.6 | 0.001 |

| D90 | 1.11 | 2.17 | 2.89 | 2.74 | -2.16 | 0.038 |

Table 3: Intragroup comparison of wound size.

Discussion

A diabetic foot ulcer is a major health concern that can lead to arthopathy and limb amputation. Microangiopathy andmacroangiopathy modify vascular status and increase the risk of infection because of hyperglycemia;peripheral neuropathy in the diabetic foot results in excessive foot pressure, foot deformities and unstable gait. Foot care and glycemic index management are crucial to preventing the development of foot ulcers. Identification of the "at-risk" foot, treatment of the acutely diseased foot and prevention of furthercomplications are the three main strategies for managing diabetic foot disease to avoid amputations of the lower extremities. In many cases, aggressive treatment of DFUs can prevent a worsening of the condition and the potential need for amputation. Therefore, the objective of therapy should be early intervention to permit prompt healing of the lesion and, once it has healed, to prevent its recurrence. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) is a portion of the plasma fraction of autologous blood with a concentration of platelets above baseline. PRP is a growth factor agonist with mitogenic and chemo tactic qualities that promote wound healing via granule, which releases locally acting growth factors. These growth factors promote tissue repair by attracting undifferentiated cells to the newly formed matrix and stimulating cell division. Similar to the method employed by Motolese et al., used PRP as a gel dressing for DFU [16]. Gel was selected for its practical use due to its painless administration and patient preference for it. Moreover, compared to PRP injections into the ulcer's floor and margins, the gel form might have a lesser risk of infection. These factors increased the suitability of PRP gel for outpatient applications. Since our institution uses normal saline as the standard dressing for DFU that is not infected, we decided to utilize it as the control group. In contrast to alternative therapy modalities that, while more successful, may have restricted access and high costs, especially in resourceconstrained regions, this one is, after all, inexpensive, accessible and easily available. Elsaid et al., found a similar proportion of gender (p=0.68) and mean age and BMI in the PRP group and NS, which were statistically not significant (p=0.74) [17]. In this study, we found no statistical difference between the PRP group and the NS group in sex, size of the affected foot, age, BMI, duration of diabetes, ABI, RBS, HbA1C, serum albumin, or platelet count. Pressure reduction is an essential component of treatment for diabetic foot ulcers. Total contact cast allows for mobility and relieves pressure over the ulcer, has established edit self as the gold standard for therapy, making patient adherence easier. It has been shown to not only interrupt the pathogenesis chain that leads to ulceration but also induce changes in the ulcer's histology. Possible disadvantages of the TCC include the need for specialized knowledge in its application, frequent cast replacements and associated expenses. According to Gupta et al., the mean duration of DM in the PRP group was 9.1 ± 5.1 and in the NS group was 10.96 ± 5.42, which was statistically not significant [11].

Ahmed M et al., found the mean ABI in the PRP group was 0.85 ± 0.04 and in the NS group was 0.83 ± 0.01 with no statistically significant difference (p=0.881) [18]. Elsaid et al., and Ahmad M et al., used a sample with statistically not significant differences in HbA1c and mean RBS between groups [17,18]. The mean platelet of PRP group was 258.44 ± 45.30 while the mean platelet of NS group was 243.22 ± 42.32. No significant difference was found in mean platelet between PRP and NS group (p=0.305), which is consistent with Elsaid et al., and Ahmed M et al., where p values were 0.78 and 0.42 respectively [17,18]. Elsaid et al., also compared the mean serum albumin levels between the PRP and NS groups, finding that they were 4.15 ± 0.26 and 4.2 ± 0.42, respectively (p=0.68) [17]. Additionally, they discovered that the PRP group's mean duration to maximum healing was 4 weeks shorter than that of the control group (6.3 ± 2.1vs.10.4 ± 1.7 weeks, P<0.0001). Likewise, Driver et al. showed that the PRP group recovered 28 days quicker on average than the control group [19].These result simply that PRP's proliferative impact may improve DFU healing. The significant difference was found in mean time to heal between PRP and NS group (p=0.001). Though it is statistically significant between the groups but it took much more time than the study by Elsaid et al, which may be due to fewer application of PRP and keeping the wounds closed by TCC for 2 weeks and wound inspection was not possible. In PRP group toal number of ulcers healed at 90 days is 14 out of 18 (77.78%) which is much better than in NS group 8 out of 18 ulcers (44.44%) which is statistically significant (p<0.05) [17]. This finding also correlates with study by Elsaid et al., but in contrast with Gupta et al., this difference may be due to difference in follow-up timings and different method of application [17,11]. When specific PUSH variables were analyzed separately, only length x width decreased significantly among healed ulcers. This may be due to the prevalence of stage 2 ulcers in the sample, the limited number of study ulcers with exudate and the small number of categories used to distinguish changes in tissue type and exudate quantity. Gardner et al found the tissue type and exudates amount did not vary significantly in each follow-up, the only variable affecting the PUSH score was the tool's length × width [20].These parameters are concomitant with this study.

Conclusion

This study, we demonstrated that both PRP and NS dressing are beneficial and effective in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer when used in conjunction with TCC in improving healing rate. Even though both treatments are beneficial, the results of this study indicate that PRP therapy is statistically superior to NS dressing. These results were consistent with those of previous research. Limitation of the study is the relatively short followup period. Diabetic foot ulcers can be chronic and slow healing wound, often requiring extended periods for complete healing and to assess the long-term efficacy of treatments. Therefore, a longer follow- up period would provide more comprehensive insights into the sustained effects of PRP therapy and NS dressing on diabetic foot ulcer healing rates.

References

- Okonkwo UA, Di Pietro LA. Diabetes and wound angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci.2017; 18:1419.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim JZ, NSL NG, Thomas C. Prevention and treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. J R Soc Med.2017;110:104- 109.

- Volmer-Thole M, Lobmann R. Neuropathy and diabetic foot syndrome. Int J Mol Sci.2016;17:917.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wen Q, Chen Q. An overview of ozone therapy for treating foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2020;360:112-119.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Viswanathan V, Snehalatha C, Sivagami M, Seena R, Rama chandran A. Association of limited joint mobility and high plantar pressure in diabetic foot ulceration in Asian Indians. Diabetes Res ClinPract.2003;60:57-61.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Netten JJ, Price PE, Lavery LA, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, et al. A. Prevention of foot ulcers in the at-risk patient with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev.2016; 32:84-92.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nather A, Cao S, Chen JLW, Low AY. Prevention of diabetic foot complications. Singapore Med J. 2018;59:291-294.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- López-Moral M, Lázaro-Martínez JL, García-Morales E, García-Álvarez Y, Álvaro-Afonso FJ, et al. Clinical efficacy of therapeutic footwear with a rigid rocker sole in the prevention of recurrence in patients with diabetes mellitus and diabetic polineuropathy: A randomized clinical trial. PLoSOne. 2019;7:14.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kavitha KV, TiwariS, Purandare VB, Khedkar S, Bhosale SS, et al. Choice of wound care in diabetic foot ulcer: A practical approach. World J Diabetes.2014,15:546-56.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas DR. Clinical management of diabetic ulcers. Clin Geriatr Med.2013; 29:433-41.

- Gupta V, Kakkar G, Gill AS,Gill CS, Gupta M. Comparative study of nano crystalline silver ion dressings with normal saline dressings in diabetic foot ulcers. JCDR.2018; 12:1-4.

- Boulton AJ, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall G, Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet.2005,12;366:1719-24.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhuet D, et al. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: Asystematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2017;49:106-116.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kale DS, Karande GS, Datkhile KD. Diabetic foot ulcer in India: Aetiological trends and bacterial diversity. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2023;27:107-114.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ramanaiah NV, Saikrishna S, Chandrasekhar C, Vamshidhar V, Ramanaiah GV, et al. A Clinical Study on efficacy of Nanocrystalline silver dressing in Diabetic foot ulcer. J of Evidence Based Med Hlthcare. 2015;45:8160-8170.

- Motolese A, Vignati F, Antelmi A, Saturni V. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma in healing necrobiosis lipoidicadiabeticorum ulcers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:39-41.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elsaid A, El-Said M, Emile S, Youssef M, Khafagy W, et al. Randomized controlled trial on autologous platelet-rich plasma versus saline dressing in treatment of non-healing diabetic foot ulcers. World J Surg. 2020;44:1294-1301.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed M, Reffat SA, Hassan A, Eskander F. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of clean diabetic foot ulcers. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;38:206-211.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Driver VR, Hanft J, Fylling CP, Beriou JM. Autologel Diabetic Foot Ulcer Study Group. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of autologous platelet rich plasma gel for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006;52:68-70.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Bergquist S, Shin CD. A prospective study of the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (PUSH).J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:93-7.10.1093/gerona/60.1.93.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

) PRP; (

) PRP; ( ) NS

) NS

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.