Effect of Lower Limb Task-Oriented Mirror Therapy on Balance, Gait and Mobility in Patients with Subacute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial

Received: 29-Nov-2023, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-121604 ; Editor assigned: 01-Dec-2023, Pre QC No. AMHSR-23-121604 (PQ); Reviewed: 15-Dec-2023 QC No. AMHSR-23-121604 (Q); Revised: 26-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-121604 (R); Published: 03-Jan-2025

Citation: Rucha A, et al. Effect of Lower Limb Task-Oriented Mirror Therapy on Balance, Gait and Mobility in Patients with Subacute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2024;14:1-16

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Stroke leads to disturbance of various brain functions leading to impairments in tone, coordination, muscle recruitment patterns and difficulty in selective joint movements. 72% of the stroke patients presents with lower limb weakness. However, gait impairments are present even after 3 months of stroke. Rehabilitation strategies available to improve function in stroke patients are often intensive and making its availability for all patients difficult. Hence, novel treatment strategies are needed to improve functional performance. Task-oriented movements induce greater cortical activity and also induces more motor recovery than movements without task. Task oriented mirror therapy is a novel combination therapy which may provide better rehabilitation outcomes after stroke. Aim: To evaluate the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke. Methodology: A pilot randomized controlled trial was conducted among 30 participants. Participants were randomized into experimental group and control group. Outcome measures like Berg Balance Scale (BBS), 10-Meter Walk Test (10 MWT) and Functional Ambulatory Category (FAC) were assessed at pre intervention and at post intervention after 4 weeks. Experimental group (n=15) received task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy and the control group (n=15) received conventional therapy. Result: The result suggested that there was signi icant difference within experimental group for outcomes like BBS, 10 MWT and FAC (p=0.0001). Experimental group exhibited signi icant difference as compared to control group for BBS (p=0.005), 10 MWT (p=0.0001) and FAC (p=0.0001). Conclusion: Task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy may improve balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke after 4 weeks of intervention.

Keywords

Mirror therapy; Task; Balance; Gait; Stroke; Mobility

Introduction

Stroke (cerebrovascular accident) is defined as a “sudden loss of neurological function caused by an interruption of the blood flow to the brain” [1]. It is one of leading causes of death and disability in India. In India, around 1.2% of overall deaths occur because of stroke [2]. Stroke in India, during the past decade showed a crude prevalence which ranged from 44.29 to 559 per lakh people per year and had a cumulative incidence which ranged from 105 to 152/100,000 people per year, in different parts of the country [3]. Stroke causes disturbance of various brain functions leading to impairments in tone, coordination, muscle recruitment patterns and difficulty in selective joint movements [4]. About 80% of stroke patients have motor impairments of upper and lower limbs after the onset of stroke whereas, 72% of the stroke patients presents with lower limb weakness [5,6]. Only half of patients with lower limb impairment are able to walk independently after the commencement of rehabilitation, while two-third of patients with lower limb impairments are unable to do so immediately after the stroke onset [7]. However, gait impairments are present even after 3 months of stroke [8]. The lower limbs are essential for transitioning between postures, walking and performing activities of daily living [9]. After the onset of stroke, balance impairment is a major concern which results in a barrier for functional performance [10]. The ability to stand after stroke can be impaired, that might have an influence on increased postural sway, reduced weight bearing on the affected limb and increased risk of falls [11]. The weakness of the lower limbs results in impairment of walking, difficulties in transfer, unsafe and inefficient ambulation. The rehabilitation of lower limb paresis is utmost importance as 30% of patients with stroke have persistent difficulties in independent ambulation [12]. Stroke-specific care that is of high quality is required due to increasing number of stroke presentations. These requirements burden the available nationwide networks [13]. Owing to this reason, new rehabilitation strategies are needed to improve quality of life in stroke patients [14].

Motor recovery pattern for upper limb and lower limb is nearly similar. The neurological motor therapies focused on the upper limb has been thoroughly investigated. Rehabilitation strategies to improve lower limb function in stroke patients includes treatments like constraint induced therapy, mental imagery and robotics assisted training which are often intensive treatment strategies and making its availability for all patients difficult [10]. Although, a few techniques such as body weight support treadmill training and motor imagery has been moderately investigated with regard to the lower limb rehabilitation [15].

Of many theories present, “neuronal group selection theory” suggests that early intervention after brain damage may be beneficial. This theory emphasizes that combining functional and task oriented activities help to enhance the brain plasticity and aids in the recruitment of suitable movement synergies. This indicates that practicing functional movement patterns is more effective as compared to isolated movements in facilitating brain plasticity [16].

Among the available treatment strategies utilized in stroke rehabilitation, the most feasible and economical treatment strategy is “Mirror Therapy”, a simple treatment that may be a suitable alternative for stroke patients [5]. Mirror therapy is regarded as a form of motor imagery that involves repeated mental practice and imagination of tasks. The active performance in the mirror therapy aids to distinguish mirror therapy from passive action observation technique [17]. It is a strategy that uses both motor imagery and action observation technique, which uses the idea of optical illusion [18]. The mirror therapy utilizes a mirror to provide a visual information by observing movements performed by the unaffected extremity. The perception of movement occurs through the activity of the affected limb, resulting in an interplay between visual, proprioceptive and motor inputs [19]. The mirror therapy intervention produces a balance between motor cortices and also fosters the interhemispheric communication [20]. The neuronal system, known as “Mirror neurons” also have considerable role in the therapeutic effect of the mirror therapy. The act of moving and watching one’s own motor activity in the mirror stimulates or excites the neurons. The recruitment of these neurons causes cortical reorganization. Research indicates that this simple and nonintrusive intervention technique possesses the capability to activate the brain, promoting a speedy recovery. Literature shows positive effects for the utility of upper limb mirror therapy. Some of the authors like, Altschuler, et al. state that individuals receiving mirror therapy treatment showed a considerable improvement over those receiving usual standard care. Additionally, Striven and Stoykov discovered significant improvements in Fugyl Meyer assessment scores, movement, speed and range of motion in individuals with stroke who underwent mirror therapy intervention for about 3-4 weeks. The first literature review for lower limb mirror therapy was conducted by Hung, et al. in 2015. In their review, it was mentioned that mirror therapy may be effective in improving motor function of the affected lower extremity in the stroke survivors, but further conclusive literature is still needed. Mohan, et al. stated no significant improvement between mirror therapy group and conventional therapy group for acute stroke patients.

Studies have showed that when healthy individuals observe their hand or knee movements through a mirror, the primary motor cortex and somatosensory cortex ipsilateral to the movement shows activation on functional brain imaging. Furthermore, Luft, et al. suggested that there is a significant activation of the contralateral primary motor cortex, supplementary motor cortex and bilateral somatosensory cortex during lower limb movements in chronic stroke.

Task-oriented training has strong evidence in stroke rehabilitation as compared to alternative motor therapies. The training consists of repetitive practice of a task which results from the movement performed and has a purposeful meaning to accomplish a goal. This approach engages different brain areas to simulate a goal-oriented task that holds real-life significance. Repetition of a task without a meaningful goal is less likely to produce cortical reorganization. Therefore, task-oriented movements induce greater cortical activity and also enhances motor recovery to a greater extent than movements without task. Therefore, the primary focus can be task or goal-oriented practice. Task-oriented Mirror Therapy is a combination therapy. Combination therapy entails the merging of two different treatment approaches. These two treatment approaches may lead to positive stacking effect resulting from the benefits of both interventions. The combination therapy may cause both way neural reorganization and enhance the motor recovery.

Literature on task-oriented mirror therapy is available for upper limb, but limited literature is available for lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy. Considering that combination therapy has been investigated to a lesser extent in lower limb stroke rehabilitation, its crucial to note that lower limb function is an important domain in rehabilitation for the patients to become independent, therefore efficient rehabilitation strategies are required for better patient outcomes. Therefore, the study aimed to evaluate the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy and conventional therapy alone on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

However, various methodological concerns arise, when implementing a high quality randomized controlled trial study (to identify harms, administrative problems and participant recruitment, etc.). Hence, conducting a pilot study has proven to be one of the most effective means to avert a failure resulting of directly implementing a full scale RCT. As a result, a pilot RCT can determine the feasibility of full scale randomized controlled trial and helps to improve its success and prevent failure. Therefore, this study protocol is outlined under a pilot RCT to determine the effect of task oriented mirror therapy on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

Research question

Is lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy effective in improving balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke?

Aim

To evaluate the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

Objectives

- To compare the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy and conventional therapy alone on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

- To determine the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

- To determine the effect of conventional therapy on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

Hypothesis

Null hypothesis: There is no significant difference between the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy and conventional therapy alone on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

Alternate hypothesis: There is significant difference between the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy and conventional therapy alone on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

Materials and Methods

Study design: Pilot RCT (pilot study with a two-group, parallel, randomized controlled trial)

Study setting: Tertiary care hospitals.

Study population: Patients with subacute stroke.

Study duration: 1 year.

Sampling technique: Convenience sampling.

Sample size: The study involved 30 participants in total. These 30 participants were randomly allocated into 2 groups with 15 participants in each group. The sample size is calculated using four factors: SD, power, significance level, group difference.

However, considering that no previous 2-arm trial has used the task-oriented mirror therapy protocol training on balance, gait and mobility in subacute stroke, values for the mean group difference and standard deviation are unknown. Although sample size calculations are not required for a pilot RCT, using the above mentioned 4 factors 32. 15 to 20 participants per group are required to ensure scientific validity of the pilot study results 51. Thus, sample size estimated and enrolled for this study was about 30 participants (15 per group) accounting the possible loss to follow-up.

Blinding: Single blinded study. Patients were blinded from the study.

Randomization technique: Block randomization method. The block randomization method is designed to randomize participants into groups with an equal sample size. This method is used to ensure a balance of sample size across groups over time. Block randomization was performed using a computer-based software. Number of blocks were 15 and block size was 2.

Allocation details: Allocation was concealed using an opaque sealed envelope.

CTRI registration number: CTRI/2023/01/049215

Inclusion criteria

- Sub-acute stroke patients (3 weeks to 6 months since onset).

- Both male and female.

- Age group between 45 to 65 years.

- Functional ambulatory category ≤ 2.

- Mini mental scale examination >24.

Exclusion criteria

- Any other associated neurological disorder.

- Severe perceptual and visual defects.

- Musculoskeletal disorders like fracture, dislocation affecting locomotion.

- History of cardiovascular instability.

- Patients with severe aphasia.

Materials required

- Data collection sheet.

- Mirror frame measuring approximately 30-inch length and 12-inch breadth for sitti lower limb mirror therapy and measuring 61-inch length and 12-inch breadth for standing lower limb mirror therapy.

- Ball.

- Door mat.

- Rocker board.

- Obstacles like cones or bottle.

- Chair with back rest support.

- Stepper/low height stool.

- Stop watch.

- Tape.

- Clinical outcome measures scales-berg balance scale, 10 meter walk test and functional ambulation category.

Procedure

- Ethical approval was taken from the institutional ethics committee prior to the start of the study following which recruitment of participants was done.

- The study was conducted in stroke population aged between 45 to 46 years.

- All the participants were assessed for eligibility criteria.

- Eligible participants were included in the study.

- All the participants were informed about the study’s objectives prior to the start of the study and signed informed consent were obtained.

- The participants were randomized and allocated into two groups-group A (Experimental group) and group B (Conventional group).

- The subjects were interviewed and the information was gathered about their demographic data, duration of stroke, health related information like past medical history and use of assistive device, etc.

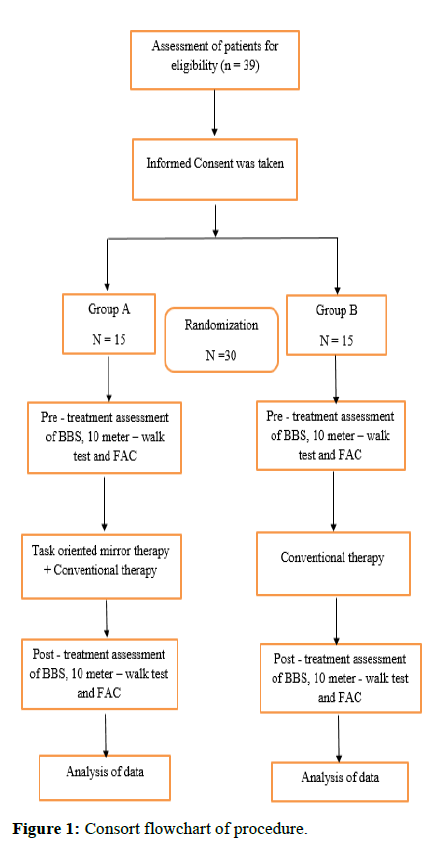

- Pre-intervention assessment of participants in both the groups was taken prior to start of intervention (Figure 1).

Intervention

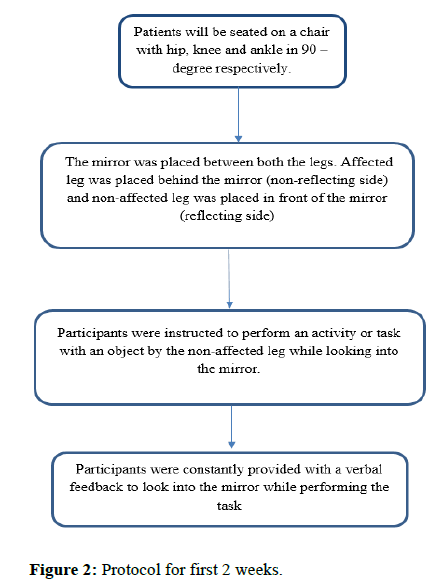

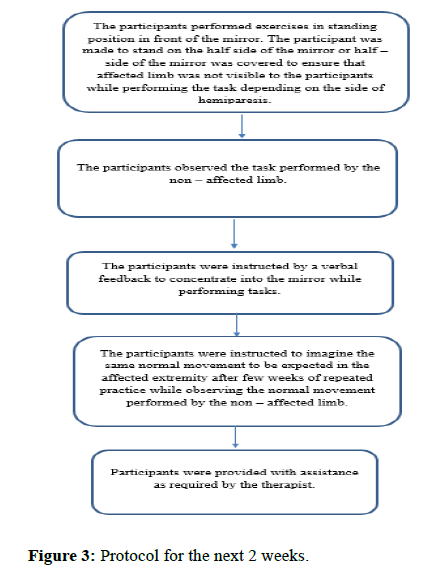

Group A: (Task-oriented mirror therapy+conventional therapy): Participants in the group A received task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy (Figures 2, 3 and Tables 1, 2).

| Task/object | Intended movement | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

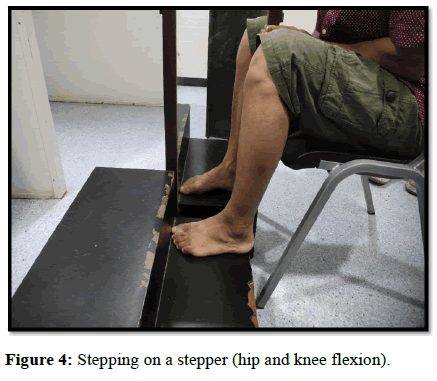

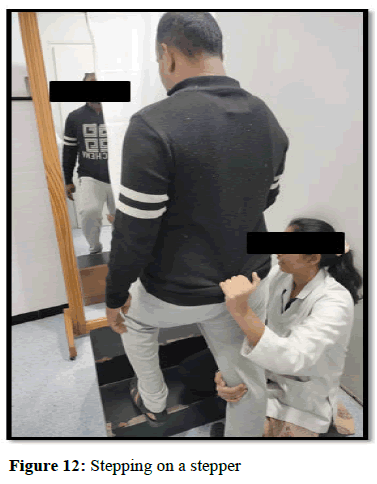

| Stepping on a low stool | Hip flexion and knee flexion | 20-50 reps |

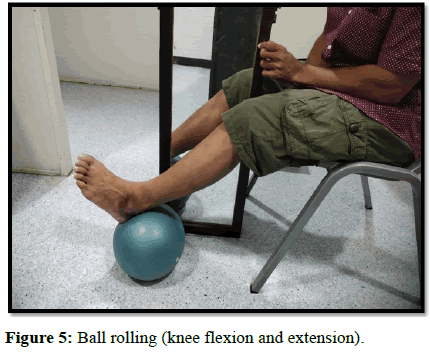

| Ball rolling | Knee flexion and extension | 20-50 reps |

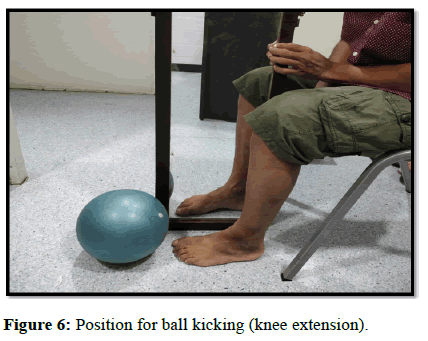

| Ball kicking | Knee extension | 20-50 reps |

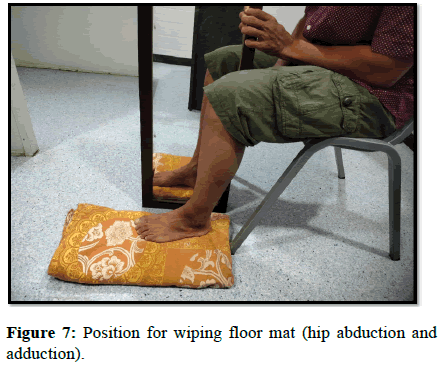

| Wiping floor mat | Hip abduction and adduction | 20-50 reps |

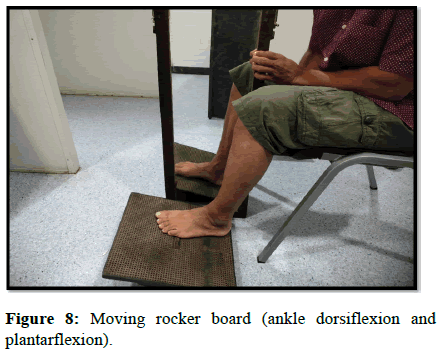

| Moving rocker board | Ankle dorsi-flexion and plantar-flexion | 20-50 reps |

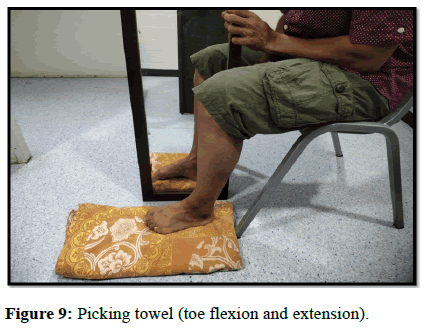

| Picking and releasing the towel | Toe flexion and extension | 20-50 reps |

Table 1: Task–oriented mirror therapy protocol in sitting position.

| Task | Dosage |

|---|---|

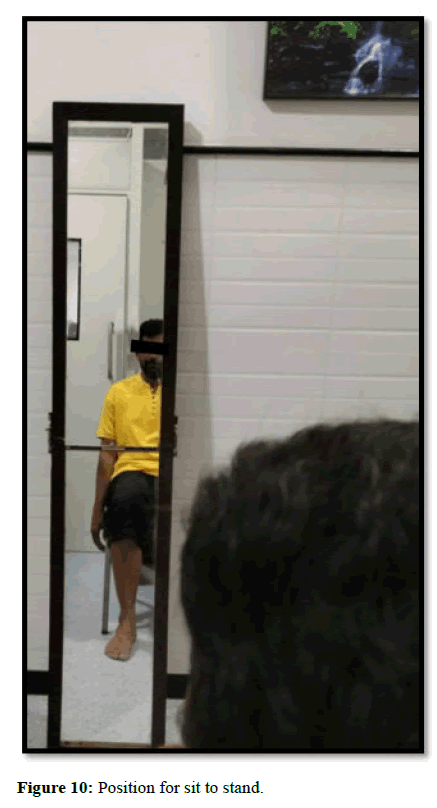

| Sit to stand | 20 reps |

| Step up and step down | 20 reps |

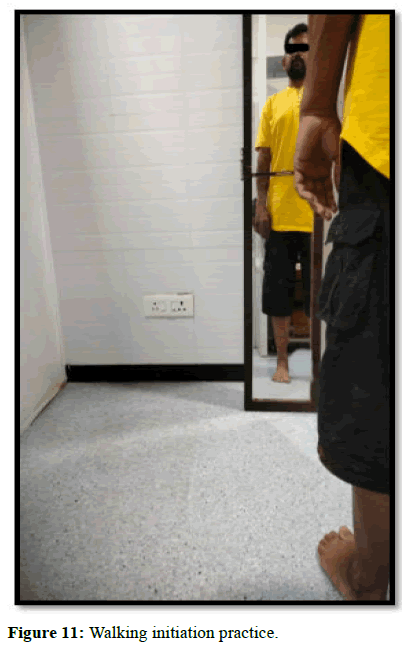

| Walking forward initiation exercise | 20 reps |

| Stepping over obstacles | 20 reps |

Table 2: Task-oriented mirror therapy protocol in standing.

- Study participants were familiarized individually with the task-oriented mirror therapy after the randomization and prior to intervention.

- A folding mirror frame which could be used for both sitting mirror therapy and standing mirror therapy was used.

- Participants were instructed to constantly concentrate on their mirrored image of the limb.

- Therapist provided with verbal commands to reinforce the patient’s concentration in the intervention.

- Total number of repetitions were tailored according to the participant’s capacity and comfort.

- Task-oriented mirror therapy was performed for 30 minutes per day with a 10-minute rest period halfway in the session (5 days/week) for a total duration of 4 weeks.

This was followed by conventional physiotherapy exercises (Figures 4-12).

Group B: (Conventional therapy): Participants in the group B received conventional therapy. The participants were provided assistance as required by the therapist (Table 3).

| Exercises | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Active assisted or active range of motion exercises Hip flexion and hip abduction Knee flexion and knee extension Ankle dorsiflexion |

10 reps each |

| Pelvic mobility exercises Pelvic bridging |

10 reps each |

| Sustained passive stretching exercises Gastrocnemius Hamstrings Adductors |

3 sets of 30 sec hold |

| Balance exercises Single limb standing on the affected side |

10 reps |

| Neurophysiological approaches (Neurodevelopmental technique or brunnstrom) |

Depending on the patient’s status |

Table 3: Conventional therapy protocol.

• Conventional exercises were performed for (5 days/week) for a total duration of 4 weeks.

Outcome measures

Balance: Berg Balance Scale - In clinical settings, the BBS has been frequently utilised to assess the quality of balance performance related to functional movement. It is made up of nine balance and five motor tasks that assess static sitting and standing balance as well as anticipatory balance during daily activities like turning, transferring, reaching, and collecting objects from the floor. The BBS is a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (unable to perform) to 4 (normal performance). The scores on each item are added together to yield a maximum total score of 56. The BBS has been demonstrated to have high intrarater and interrater reliabilities (ICC=0.99 and 0.98, respectively). The score is divided into three categories: 0-20 indicates poor balance, 21-40 indicates intermediate balance and 41-56 indicates excellent balance.

Gait: 10-Meter Walk test - The 10-meter Walk Test (mWT) is used to determine gait speed in meters per second (m/s). When any part of the leading foot crosses the plane of the 2 m mark, the timer starts and when any part of the leading foot crosses the plane of the 8 m mark, the timer is stopped. To obtain the gait speed in meters per second (m/s) divide 6 meters by the seconds (time taken to finish a 6-meter distance). The amount of physical assistance to complete the test is also documented. The interrater reliability of the 10-meter walk test in patients with subacute stroke is 0.96.

Mobility: Functional ambulatory category - It estimates the ability to ambulate. It requires 15 meters of indoor floor to administer the test. This 6-point scale assesses ambulation status by influencing how often assistance is required when walking, regardless of whether or not they used a specific assistive device. This 6-point scale depicts the patient's functional abilities, from non-functional ambulation to autonomous ambulation including independent stair climbing. FAC's test-retest and interrater reliability are 0.95 and 0.90, respectively, and its concurrent validity with walking velocity is 0.90 at 6-month follow up.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was done using SPSS 27.0 version software. The results were considered significant at p<0.05 and Confidence Interval (CI) at 95 %. The normality of data was tested by Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Analysis was done using chi square test for descriptive and inferential data, student’s paired t-test was used to compare within groups, unpaired student’s t-test was used to compare between groups and chi square test was used for categorical variables. For quantitative variables the mean and standard deviation was calculated and for categorical variables frequency and proportions were calculated. The data was represented using tables and in form of visual impressions such as bar diagram.

Results

Total 30 participants based on the eligibility criteria were recruited in the study into 2 groups. Group A: Experimental group and Group B: Control group.

The results are based on all 30 participants. There were no dropouts during the study. The baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in Tables 4-8.

| Age group (years) | Experimental group | Control group | ê?2-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45-55 years | 10 (66.67%) | 6 (40%) | 2.14, p=0.14, NS |

| 56-65 years | 5 (33.33%) | 9 (60%) | |

| Total | 15(100%) | 15 (100%) | |

| Mean ± SD | 52.66 ± 6.48 | 55.73 ± 6.89 | |

| Range | 45-64 years | 45-65 years |

Table 4: Distribution of patients in two groups according to age in years.

| Gender | Experimental group | Control group | ê?2-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 11 (73.33%) | 10 (66.67%) | 0.15, p=0.69, NS |

| Female | 4 (26.67%) | 5 (33.33%) | |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) |

Table 5: Distribution of patients in two groups according to gender.

| Type of stroke | Experimental group | Control group | ê?2-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhagic | 4 (26.67%) | 5 (33.33%) | 0.15, p=0.69, NS |

| Ischemic | 11 (73.33%) | 10 (66.67%) | |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) |

Table 6: Distribution of patients in two groups according to type of stroke.

| Side affected | Experimental group | Control group | ê?2-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right side | 10 (66.67%) | 9 (60%) | 0.14, p=0.70, NS |

| Left side | 5 (33.33%) | 6 (40%) | |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) |

Table 7: Distribution of patients in two groups according to side affected.

| Type of assistance used | Experimental group | Control group | ê?2-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cane | 6 (40%) | 7 (46.67%) | 0.82, p=0.65, NS |

| Cane+manual assistance | 4 (26.67%) | 2 (13.33%) | |

| Manual assistance | 5 (33.33%) | 6 (40%) | |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) |

Table 8: Distribution of patients in two groups according to type of assistance used.

Table 4 to 8 shows that demographic characteristics showed non-significant difference between groups (p-value=0.65).

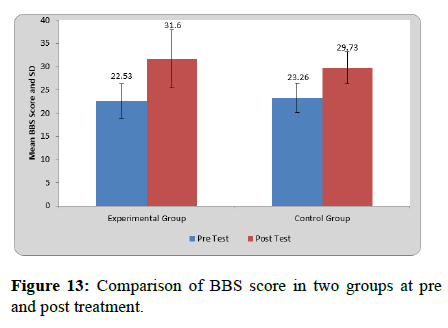

Mean BBS score at pre-treatment in experimental group was 22.53 ± 3.81 and at post-test was 31.60 ± 6.23. By using student’s paired t test statistically significant difference was found in BBS score at pre and post treatment in experimental group (t=12.36, p=0.0001).

Mean BBS at pre-treatment in control group was 23.26 ± 3.10 and at post-test it was 29.73 ± 3.45. By using student’s paired t test statistically significant difference was found in BBS score at pre and post treatment in control group (t=15.25, p=0.0001).

On comparing mean difference in BBS among patients of two groups by using student’s unpaired t test statistically significant difference was found in between two groups (t=3.07, p=0.005).

The mean between group difference of BBS showed more improvement in the experimental group when analyzed after 4 weeks of treatment (Table 9 and Figure 13).

| Group | Pre-test | Post-test | Mean difference | Student’s paired t test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 22.53 ± 3.81 | 31.60 ± 6.23 | 9.06 ± 2.84 | 12.36, p=0.0001, S |

| Control group | 23.26 ± 3.10 | 29.73 ± 3.45 | 6.46±1.64 | 15.25, p=0.0001, S |

| Comparison of mean difference in two groups (Student’s unpaired t test) | t–value | 3.07 | ||

| p–value | 0.005, S | |||

Table 9: Comparison of BBS score in two groups at pre and post-treatment.

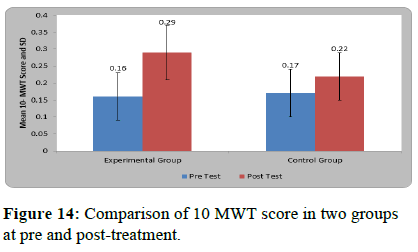

Mean 10 MWT at pre-treatment in experimental group was 0.16 ± 0.07 and at post-test was 0.29 ± 0.08. By using student’s paired t test statistically significant difference was found in 10 MWT score at pre and post treatment in experimental group (t=12.11, p=0.0001).

Mean 10 MWT score at pre-treatment in control group was 0.17 ± 0.07 and at post-test it was 0.22 ± 0.07. By using student’s paired t test statistically significant difference was found in 10 MWT score at pre and post treatment in control group (t=10.31, p=0.0001).

On comparing mean difference in 10 MWT among patients of two groups by using student’s unpaired t-test statistically significant difference was found between two groups (t=5.84, p=0.0001) (Table 10 and Figure 14).

| Group | Pre-test | Post-test | Mean difference | Student’s paired t test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 12.11, p=0.0001, S |

| Control group | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.07 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 10.31, p=0.0001, S |

| Comparison of mean difference in two groups (Student’s unpaired t test) | t–value | 5.84 | ||

| p–value | 0.0001, S | |||

Table 10: Comparison of 10 MWT score in two groups at pre and post-treatment.

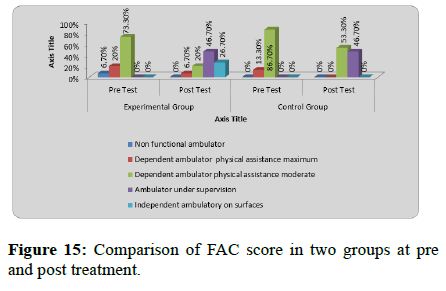

FAC score improved significantly for experimental group (p=0.0015) and control group (p=0.0061) after treatment.

The experimental group showed more improvement for FAC score as compared to control group after 4 weeks of treatment (p=0.0001) (Table 11 and Figure 15).

| FAC score | Experimental group | Control group | ê?2-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | ||

| Nonfunctional ambulator (0) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 38.82, p=0.0001, S |

| Dependent ambulator physical assistance maximum (1) | 3 (20%) | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Dependent ambulator physical assistance moderate (2) | 11 (73.3%) | 3 (20%) | 13 (86.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | |

| Ambulator under supervision (3) | 0 (0%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Independent ambulator on surfaces (4) | 0 (0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Total | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) | 15 (100%) | |

| ê?2-value | 17.57, p=0.0015, S | 10.19, p=0.0061, S | |||

Table 11: Comparison of FAC score in two groups at pre and post treatment.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to determine the effect of lower limb task-oriented mirror therapy on balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke. The participants in the study were evaluated for three outcome measures which included berg balance scale for balance, 10 meter walk test for gait and functional ambulatory category for mobility. The results of the study showed significant improvement in both experimental and control group for BBS, 10-MWT and FAC after 4 weeks of intervention. However, between group comparison showed significant improvement in BBS, 10-MWT and FAC (p=0.005, 0.0001, 0.0001 respectively) for the experimental group after 4 weeks of intervention. Thus, interpreting that task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy may have added effect in improving balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke.

Mirror therapy was more effective in the subacute stage of stroke; as neural plasticity occurs early in the stage of stroke. Considering this our study underwent the intervention during subacute stage of the stroke. The mechanism of mirror therapy as mentioned by a previous study indicated that, it aids in improving motor control and motor recovery in patients with post-stroke. Following the application of the mirror therapy, there might be an activation of the occipital area on the side of lesion because of visual perception of the movement. Further, the primary somatosensory cortex would get activated on the affected side. After multiple sessions following mirror therapy, the premotor cortex may be activated. There seems to be increased activation of the corticospinal tracts noted on the affected side following the mirror therapy.

The other theory for improving motor control is the role of “Mirror neurons”. The observation of movement is an important aspect of mirror therapy. A set of neurons known as “Mirror neurons” might be activated during observation of a movement as well as performance of the movement. These neurons may aid in reorganizing the damaged brain areas and in improving the motor control. A study conducted by Kamal Narayan et al. mentioned that the activation and firing of mirror neurons is more for object directed tasks as compared to non-object-based movements.

One of studies on task-specific training has stated that repetition plays a crucial role to induce cortical changes after task practice. Therefore, to augment the activity of mirror neurons as mentioned by previous literature we included mirror therapy along with various tasks, that may have contributed to motor recovery and better functional performance in our study.

Another study conducted by Kamal Narayan, et al. on hand function stated that participants were not instructed to perform any movement on the affected limb, however minimal involuntary movements in the hand and fingers were noted. Similar mirrored movements were observed in toes and ankle among few patients in our study. The mirrored movements resulted as interhemispheric inhibition was disrupted because of damage to unilateral part of the cortex.

The results of BBS, 10-MWT and FAC are suggestive of effects of task-oriented mirror therapy in improving functional mobility and functional performance. Our findings suggest that incorporating mirror therapy with task-oriented exercises might be beneficial in improving balance, gait and mobility. The mirror therapy protocol in our study included flexor synergy items in sitting. It included hip-knee flexion and ankle dorsiflexion movements integrated with various tasks during the treatment. This was in accordance with the study conducted by Kamal Arya, et al.

One of studies conducted by Mohan, et al. included the movements of hip abduction-external rotation and the reverse movement. Our study protocol also included the hip abduction and adduction movement integrated with the task of wiping the floor mat. Further, Sutbeyaz, et al. underwent mirror therapy protocol with ankle dorsiflexion movement. Our study included ankle dorsiflexion movement with task of moving the rocker board. The majority of movements included in our study were in accordance with the past studies. However, our study integrated the movements with various tasks. Very limited studies have utilized mirror therapy along with task-based exercises.

The improvement in balance was observed in our study after task-oriented mirror therapy intervention. A study conducted by Myoung Kwon, et al. found improvement in stability index and medial and lateral stability index as assessed by biodex balance system following the application of mirror therapy in subacute stroke patients. This study utilized balance platform for determining the balance assessment. However, our study assessed balance by berg balance scale. Both the studies reported improvement in balance after the intervention.

A study conducted by Syeda Zeba, et al. mentioned that after lower limb mirror therapy intervention, experimental group (p<0.0001) showed improvement in balance as assessed by berg balance scale. However, between group analysis mentioned that experimental and control group showed no significance difference in balance. Our study showed significant difference between experimental and control groups for balance. Both the studies mentioned above underwent mirror therapy intervention without tasks. However, our study underwent task – based mirror therapy. Thus, inter pretating that task-oriented mirror therapy may be more beneficial in improving balance.

One of the studies conducted by Mohan, et al. assessed balance by brunnel balance assessment in acute stroke patients. The experimental group which received lower limb mirror therapy had significant improvement in balance after 2 weeks of intervention. Whereas, no between group difference was noted in this study. However, our study observed significant improvement in the experimental group (p=0.005) as compared to the control group for balance. The rationale might be, as our study underwent mirror therapy protocol during the subacute stage of the stroke, whereas Mohan et al. underwent mirror therapy during acute stage of stroke.

It has been demonstrated that balance issues prevent stroke patients from increasing their walking speed. Hence, a seated mirror therapy exercise program might be beneficial initially. Therefore, our study included a protocol in sitting for first two weeks. It enhances equilibrium, improves patient’s ability to walk better without supervision, as required for actual walking practice. One of the studies has mentioned that mirror therapy is a safe intervention that can be incorporated in sitting position for both non–ambulatory and ambulatory stroke patients.

The findings of the previous literature have stated that action observation, aids to facilitate the recruitment of stored motor programs, which in turn aid in efficient movement execution and recovery. Our study included standing mirror therapy protocol where, action observation of the non-affected limb could potentially lead to the activation of stored programs of movement. As mentioned by Elena Marques et al. the plasticity related changes in the sensorimotor areas comprising of the mirror neurons may be involved in the process of motor recovery. This could have contributed to the positive results of balance and mobility in our study.

The improvement in gait was observed in our study after task-oriented mirror therapy intervention. A study done by Kamal Narayan et al. found no improvement in gait speed as observed by 10–MWT, but Rivermead visual gait assessment items like hyperextension of knee improved as there was knee flexor activation following mirror therapy. However, our study showed improvement in walking velocity (p=0.0001). The combination of mirror neuron system contributing to motor recovery in addition to task oriented training (sit to stand, stepping over obstacle, stepping on stool and walking initiation) may lead to increase in the extensor muscle force production and strength 30 during standing mirror therapy that might have contributed to the improvement in the walking speed.

A study conducted by Sang Gu ji, et al. assessed temporal and spatial parameters of gait, however our study included walking velocity to determine gait function. Further, the study stated that mirror therapy may be utilized to improve gait impairments after stroke. These findings may be supported by our study as well. According to a study, mirror therapy was effective for improving gait speed and motor recovery when compared to sham mirror therapy. Further, it was mentioned that mirror therapy is an adjunct to conventional physical therapy.

The improvement in mobility was observed in our study after task-oriented mirror therapy intervention. Kritika Verma, et al. observed improvement in FAC in the experimental group [4]. Mohan et al. similarly observed improvement in FAC after mirror therapy intervention. Both the study findings are in accordance with our study. The improvement in mobility might be a result of improvement in balance and walking speed which reflects the motor recovery.

Our study findings emphasize that a task-oriented approach may lead to cortical reorganization and mirror therapy may enhance the cortical excitability. Both of which contribute to motor recovery. Thus “combination approach” might have contributed to positive outcomes in our study.

Conclusion

Task-oriented mirror therapy along with conventional therapy might be beneficial in improving balance, gait and mobility in patients with subacute stroke after 4 weeks of intervention.

Strength of the Study

• This is among the few intervention protocols which included the task-oriented mirror therapy in standing position.

• Intervention protocol was progressed after 2 weeks from sitting position exercises to standing position exercises.

• The adherence to the treatment throughout the study duration is noteworthy, as all 30 participants completed the study without any dropouts, which was one of the positive outcomes of the study.

Limitations

• There was an absence of long-term follow up.

• The lack of reliable objective method to determine the amount of illusion during intervention was not considered.

• Study did not use neuroimaging techniques to determine cortical reorganization after the intervention.

Future Scope

• A larger sample size with another combination therapy involving mirror therapy and some other intervention would be preferable in future studies.

• Further studies can be done to determine the patterns of activation in the cerebral cortex during lower limb taskoriented mirror therapy in sitting and standing positions using fMRI.

• Effect of intervention on quality of life can also be investigated.

• Long term effects of the intervention can be investigated.

• Protocol can be modified according to different stages of stroke.

Clinical Implication

• This intervention may help to induce the movement on the paralytic limb, thereby facilitating motor recovery and aids to improve balance, gait and mobility after stroke.

• Combination approach of task–oriented training along with mirror therapy may have benefits stacked to improve functional performance of lower limb.

• This combination approach may be one of the treatment strategies that aids to maximize independence after stroke.

Informed Consent

Informed consent of patient was taken.

Acknowledgment

We thank the participants who contributed in the study.

Funding

The study has not received any external funding.

Author Contributions

RA, AK conceptualized the entire protocol of study, RA collected data and RA and AK drafted the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Susan B. O’ Sullivan. Thomas J. Schmitz. George D. Fulk. Sixth edition. 2014.

- Banerjee TK, Das SK. Epidemiology of stroke in India. Neurol Asia. 2006;11:1-4.

- Kamalakannan S, Gudlavalleti AS, Gudlavalleti VS, Goenka S, Kuper H. Incidence and prevalence of stroke in India: A systematic review. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146:175-185.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Verma K, Kaur J, Malik M, Thukral N. The effectiveness of mirror therapy with repetitions on lower extremity motor recovery, balance and mobility in patients with stroke. Romanian J Neurol. 2021;20:153-160.

- Khakashan SZ, Manjunatha H. A comparative study on the effect of mirror visual feedback therapy verses conventional physiotherapy in the improvement of the hemiplegic gait rehabilitation in subjects with chronic stroke. Int J Physical Education Sports Health. 2021;8:224-228.

- Tsaih PL, Chiu MJ, Luh JJ, Yang YR, Lin JJ, et al. Practice variability combined with task-oriented electromyographic biofeedback enhances strength and balance in people with chronic stroke. Behav Neurol. 2018;2018:1-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen HS, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:27-32.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng MF, Tong RK, Li LS. A pilot study of randomized clinical controlled trial of gait training in subacute stroke patients with partial body-weight support electromechanical gait trainer and functional electrical stimulation: Six-month follow-up. Stroke. 2008;39:154-160.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arya KN, Pandian S, Kumar V. Effect of activity-based mirror therapy on lower limb motor-recovery and gait in stroke: A randomised controlled trial. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2019;29:1193-210.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim MK, Ji SG, Cha HG. The effect of mirror therapy on balance ability of subacute stroke patients. Hong Kong Physiother J. 2016;34:27-32.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yavuzer G, Eser F, Karakus D, Karaoglan B, Stam HJ. The effects of balance training on gait late after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2006;20:960-969.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Broderick P, Horgan F, Blake C, Ehrensberger M, Simpson D, et al. Mirror therapy for improving lower limb motor function and mobility after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2018;63:208-220.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mathieson S, Parsons J, Kaplan M, Parsons M. Combining functional electrical stimulation and mirror therapy for upper limb motor recovery following stroke: A randomised trial. European J Physiother. 2018;20:244-249.

- Dundar U, Toktas H, Solak O, Ulasli AM, Eroglu S. A comparative study of conventional physiotherapy versus robotic training combined with physiotherapy in patients with stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2014;21:453-461.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oostra KM, Oomen A, Vanderstraeten G, Vingerhoets G. Influence of motor imagery training on gait rehabilitation in sub-acute stroke: A randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47:204-209.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohan U, Kumar KV, Suresh BV, Misri ZK, Chakrapani M. Effectiveness of mirror therapy on lower extremity motor recovery, balance and mobility in patients with acute stroke: A randomized sham-controlled pilot trial. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013;16:634-639.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thieme H, Morkisch N, Mehrholz J, Pohl M, Behrens J, et al. Mirror therapy for improving motor function after stroke: Update of a Cochrane review. Stroke. 2019;50:e26-7.

- Bhasin A, Srivastava MP, Kumaran SS, Bhatia R, Mohanty S. Neural interface of mirror therapy in chronic stroke patients: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neurol India. 2012;60:570-576.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arya KN, Pandian S, Kumar D, Puri V. Task-based mirror therapy augmenting motor recovery in poststroke hemiparesis: a randomized controlled trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:1738-1748.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avanzino L, Raffo A, Pelosin E, Ogliastro C, Marchese R, et al. Training based on mirror visual feedback influences transcallosal communication. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40:2581-2588.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.