Metabolic Syndrome and its Association with Quality of Life among Middle Aged Urban Residents in West Ethiopia

2 Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Jimma University, Jimma, Ethiopia

Received: 05-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-94402; Editor assigned: 10-Apr-2023, Pre QC No. AMHSR-23-94402 (PQ); Reviewed: 24-Apr-2023 QC No. AMHSR-23-94402; Revised: 19-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-94402 (R); Published: 16-Aug-2023

Citation: Alemu A, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and its Association with Quality Of Life among Middle Aged Urban Residents in West Ethiopia. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2023;13:748-757.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Metabolic syndrome is a major health disorder facing all people and obesity become epidemic worldwide. In developing countries, undiagnosed Mets constitutes a challenge for health providers; screening healthier community for mets and poor quality of life was not practiced, especially in west Ethiopia.

Objective: To assess magnitude and association of Mets with HRQoL among undiagnosed middle aged urban residents of west Ethiopia.

Methods: A community based cross sectional study design was applied on 266 unscreened healthy adults from February 01, 2019 to March 01, 2019. By using SPSS version 24, an association of MetS and HRQoL was indenti ied. Statistically signi icant of variables were considered at p ≤ 0.05 on multivariable logistic regression analysis.

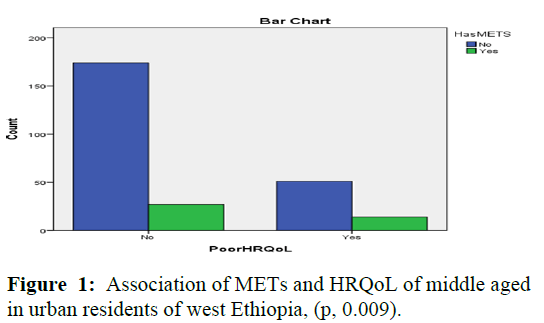

Results: The overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 15.4% and majority (91.7%) of participants had poor healthy lifestyles. By separate components the most frequent metabolic syndrome parameters; central obesity, blood pressure, hyperglycemia and low density lipoprotein were 58.6%, 18.4%, 24.4%, 20.4% and 19.5% respectively. Findings of multivariable showed mobility problem was associated signi icantly with metabolic syndrome (AOR: 7.53; 95% CI: 2.00-12.70; p, 0.003). Similarly, those who had serum TG level ≥ 150 mg/dL was found to increased risks of metabolic syndrome by more than one hundred thirteen times (OR=113.18 CI=36.05-355.29) and higher odds of being having metabolic syndrome were noted likely in depressed respondents after adjustment (AOR: 1.46; 95% CI, 1.13-1.65, p=0.233), however not signi icant. Likewise, HRQoL con irms signi icant association with metabolic syndrome (p, 0.009).

Conclusion: This study reveals modi iable risks factors, undiagnosed METs and poor health related quality of life were prevalent and associated in urban residents of west Ethiopia. Therefore, educating community on healthy lifestyles and creating awareness on metabolic syndrome were signi icant to improving quality of life and mitigate non-communicable diseases.

Keywords

Metabolic syndrome; Healthy lifestyles; Quality of life; Middle aged; West Ethiopia

Introduction

The global prevalence of NCDs is increasing rapidly, including low and middle income countries and in 2012 almost 75% of NCD-related deaths where took place. In developing countries, over-nutrition is second ‘silent emergency’ due to rapid urbanization and shifting of diet and 79% of deaths attributable to chronic diseases are occurring mostly during middle aged. In 2000 WHO reported that about 800,000 cases were recorded in Ethiopia and this number projected to rise to 1.8 million by 2030. Also WHO reported in 2013 showed about 1.9 million diabetic patients seen in Ethiopia. Findings from Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital also reveals 9.9% of undiagnosed employees in that hospital were at high risk for developing T2 DM and about 13.9% of the female had gestational diabetic mellitus [1].

Risks of NCDs are increasing as a result of unhealthy lifestyles, such as tobacco, unhealthy diet, risky alcohol drinking and physical inactivity. Metabolic syndrome is of the result of interconnected physiological, biochemical, clinical and metabolic factors. It also defined as having abdominal obesity plus any two or more of the following risk factors: Elevated blood pressure, reduced High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C), elevated triglyceride levels and raised fasting plasma glucose [2].

Unhealthy lifestyles are the most common modifiable risk factors of metabolic syndrome. The impact of unhealthy lifestyles not only undermines quality of life and productivity, but also contributes death and economic losses. Morbidity costs represent lost income from reduced productivity, restricted physical activity and absenteeism and bed days. Mortality costs encompass lost future income due to premature death. According to Ethiopian public health institute report in 2016, the cumulative economic losses due to NCD burden in low and middle income countries between 2011 and 2025 have been estimated US $7 trillion. Population norms for HRQoL are an essential ingredient in health economics and in the evaluation of population health [3].

Degenerative diseases can be delayed, prevented or managed through healthy behaviors, yet lifestyles-related health risk factors is still lack focus. In 2013, the American medical association classified obesity as a disease. It is most commonly caused by a combination of unhealthy diet, physical in activities and genetic susceptibility. Dieting and exercising is medicine for obesity and reducing disability and death from chronic diseases. Promotion of healthy diets and of physical activity should be a core competence of primary care providers, who play an important role in providing individual services to tackle the burden of NCDs. Nutrition transition exacerbated by decreased physical activity, stressful lifestyle, risky alcohol drinking and tobacco use [4]. Many researchers argued, improve the quality of life mean to reduce health inequalities. Because it systematically measuring the relationship between health and health status with quality of life. It is important to note that certain domains and the factors related to those domains might be especially influential for subjects’ HRQoL [5].

Study conducted in Addis Ababa revealed, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 14.0% in men and 24.0% in women. Similarly; according to IDF definition in the study population the overall prevalence rate of Metabolic Syndrome (Met S-IDF) in Jimma town was estimated to be (16.7%). Even though metabolic syndrome is prevalent in urban areas particularly workforces and women, in Ethiopia the effect not yet registered nationwide. Also Ethiopia had no optimal cut-off points for defining metabolic syndrome and risk components of adults, rather than using cot-off points from caucasian population. Screening for metabolic disorders among healthy individuals is ignored as the literatures showed; evidence also suggests that an abnormal metabolic profile, rather than high BMI, is associated with higher risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases [6].

In line with the concept, because of chronic degenerative diseases most of young age adults are dying due to biological age than chronological ageing. Unless risk factors of metabolic syndrome are prevented earlier, the consequences range from serious chronic conditions like stroke, type II diabetes, hypertension, selected types of cancer and distortions of quality of life to premature death. Therefore, this study aimed to assess prevalence and association of metabolic syndrome with quality of life among unscreened middle aged urban residents in west Ethiopia [7].

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

A community based cross-sectional study design was adopted in accordance with approaches of WHO to conduct the research on middle age urban residents in west Ethiopia. Because of hub center for western towns (Assosa, Ambo, Bure-Bahirdar, Metu and Jimma) we selected Nekemte. It is 328 km far from Addis Ababa (Finfinne) and have six kebeles. Its city projection in 2017 is estimated to be 117,819 and out of this adults 51% (117,819=60,088). This town has one specialized hospital, one referral hospital and three health centers community based education on healthy lifestyle adoption, prevention of risk factors of metabolic syndrome and improvement of quality of life was being given from 1 February-1 August 2019, so these results serve as baseline [8].

Source and study population

All middle aged adults (41-64 years) living in Nekemte town during the study time were the source of population. While all middle aged (41-64 years) adults in the selected communes and registered as a resident and had lived in community for greater than six months were be included in study population [9].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants who lived at least six months and aged 41 to 64 years who were eligible to participate in the study However, those on medication and have known cardiovascular disease; attended behavioral change communication program; pregnant and lactating; bariatric surgery; us anti-psychotics and physically disables were excluded [10].

Sample and sampling techniques

Two hundred sixty six participants calculated using a single finite population proportion formula by using Epi Info™ 7 by considering with the following assumptions: Margin of error of 5%, confidence level of 95%, 80% power, 10% nonresponse rate and central obesity (19.6%) the most common prevalent metabolic syndrome component Ethiopian adults [11].

From six kebeles (small administrative unit), two kebeles which were not adjacent but homogeneous in terms of socioeconomically and geographically were selected. Since data was used as baseline for an intervention, one kebele was randomly selected and the other was purposively allocated with buffering zone through natural geography to avoid data contamination [12].

Data collection

Data were gathered using structured questionnaires through interview of adults in the local language that translated from English version by trained research assistants. Self administered questionnaires and anthropometric and biochemical measurements were used to collect data. Anthropometric assessment of adults carried out using standardized techniques. Weight and height measurements will be taken using calibrated equipment (Taylor lithium electronic scale for weight and a portable stadiometer/sac- Germany) with light clothes and no shoes [13].

For laboratory analysis, 5 ml of venous blood samples from the ante-capital vein was taken after. The study participants were advised to take an overnight fasting of 10-12 hours before collecting the blood samples for the determination of FBG and lipid profiles. Fasting blood (plasma) glucose, serum total cholesterol, HDL-C and triglycerides were determined by auto analyzer (human star model 80) method by using specific reagents (human). LDL-C was calculated using the Freidwald formula. VLDL=Triglycerides÷5; LDL=Total cholesterol-(HDL+VLDL). The anthropometric assessment was done according to the standardized procedures stipulated by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) anthropometric indicators measurement guide by seca Germany [14,15].

Operational definitions

Metabolic syndrome was defined as presence of central obesity as defined by (waist circumference 83.7 cm for males and 78.0 cm for females, BMI> 22.2 in men and 24.5 kg/cm2 in women since Ethiopian have 10% less slim 24 which is equivalent to (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2); plus any two of the following factors: Raised triglycerides level: ≥ 150 mg/dl (1.7 m mol/L), reduced HDL-cholesterol: <40 mg/dl (1.03 m mol/ L) in males and <50 mg/dl (1.29 mmol/L) in females, raised blood pressure: Systolic BP ≥ 130 or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg and raised Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG) ≥ 100 mg/dl (5.6 m mol/L) [16].

Diet diversity was constructed according to FAO 2013, by counting the intake of the food groups over a period of one week based on the sum of food groups consumed over the reference period. For instance, an adult who consumed one item from each of the food groups at least once during the week would have the maximum DDS. Poor Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) defined by using WHO guideline and if the participants had one and/or more number of poor/ complaint from the five domains of EQ-5 D [17].

Data analysis

Data analyses were done using SPSS for windows version 24 (Chicago, Illinois) after checking for missing values and outliers. Descriptive analysis was carried out using risk score as dependent variable, with age, gender, smoking, physical activity, BMI, WC, ethnicity, educational status, religion, income, fruits and vegetables eating habit, previously measured history of blood glucose and pressure, presence of metabolic syndrome [18].

Regression analysis was used to identify the factors associated with metabolic syndrome and health related quality of life. Binary logistic regression was used to determine the association between lifestyles with modifiable risk factors of metabolic syndrome and health related quality of life. Variables with p-value ≤ 0.25 in binary analysis was selected as candidate variables multivariable logistic regression model to identify association of independently factors. Odds ratio together with their corresponding 95% CI was computed. Multi-colinearity among independent variables was assessed using the standard errors. The standard errors for regression coefficients <2.0, as a familiar cutoff value, showed that there was no multicollinearity among independent variables. Normality was checked for continuous variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant [19].

Results

Socio demographic characteristics of participants

From two hundred sixty six undiagnosed populations 62.8% were females. On average the age of study participants were 52.5 years and largest population (89.5%) was Oromo followed by Amhara (6%). Likewise, 41.4% of the respondents were live in lowest wealth quintiles. Similarly, almost all (92.5%) of respondents did not have urban farming/home gardening and 54.9% of them living below poverty threshold (Table 1) [20].

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 167 | 62.8 |

| Male | 99 | 37.2 | |

| Age in years | 41-48 | 145 | 54.5 |

| 49-56 | 77 | 28.9 | |

| 57-64 | 44 | 16.5 | |

| Educational status | Illiterate | 86 | 32.3 |

| Some school | 119 | 44.7 | |

| Diploma/Certificate | 33 | 12.4 | |

| Degree and above | 28 | 10.5 | |

| Marital status | Single | 13 | 4.9 |

| Married | 178 | 66.9 | |

| Widowed | 56 | 21.1 | |

| Divorced | 19 | 7.1 | |

| Religious | Protestant | 160 | 63.9 |

| Orthodox | 88 | 33.1 | |

| Muslim | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Wakefata | 11 | 0.4 | |

| Others | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Ethnicity | Oromo | 238 | 89.5 |

| Amhara | 16 | 6 | |

| Tigre | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Others | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Occupation status | Job less | 135 | 50.8 |

| Light work | 30 | 11.3 | |

| Long hour sitting work | 61 | 22.9 | |

| Long stand work >4 hrs | 40 | 15 | |

| Estimated average monthly income | <37.5 USD | 146 | 54.9 |

| 37.5-75 USD | 74 | 27.8 | |

| 75-100USD | 9 | 3.4 | |

| >100 USD | 37 | 13.9 | |

| Urban farming | Yes | 20 | 7.5 |

| No | 246 | 92.5 | |

| Health insurance | Yes | 7 | 2.6 |

| No | 259 | 97.4 | |

| Wealth quintiles | Lowest/the poorest | 110 | 41.4 |

| Second quintiles | 80 | 30.1 | |

| Middle quintiles | 68 | 25.6 | |

| Fourth quintiles/richest | 8 | 3 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants, urban, west Ethioipa 2019.

Common modifiable risk factors

Out of the 266 participants, small number of participants (2.3%) were currently smoking cigarette. Similarly, 9.8% of participants were currently drink risk alcohol and 1.1% chew khat. Almost (98.9%) respondents consuming saturated oil and only 24.8% of them were consuming vegetables at least five services or slices per day. More than two third (68%) respondents had low dietary diversity score. Large proportion of participants (91.0%) was engaged in low physical activity. Similarly, more than half (58.6%) of the participants were found to have central obesity (high waist circumference) (Table 2).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Current smoker | 6 | 2.3 |

| Former, but quit now | 21 | 7.9 | |

| Never smoker | 239 | 89.8 | |

| Alcohol | Current drunker | 26 | 9.8 |

| Former, but quit now | 40 | 15 | |

| Never | 200 | 75.2 | |

| Khat | Current chewer | 3 | 1.1 |

| Former, but quit now | 18 | 6.8 | |

| Never | 245 | 92.1 | |

| Physical activity | Physical inactive (Low PA) | 242 | 91 |

| Moderate (3 ds and 120 m’/wk-150 m’/wk) | 13 | 4.9 | |

| Vigorous (≥ 3 days/150 m’/wk) | 11 | 4.1 | |

| Sleep | Yes I have apnea | 92 | 34.6 |

| Sometimes fragmented | 108 | 40.6 | |

| Normal | 66 | 24.8 | |

| Salt | Yes, use >1 teaspoon/>6 g/day | 266 | 100 |

| As of standard/<6 g/day | 0 | ||

| Sugar | Use excess dose | 261 | 98.1 |

| As of standard | 5 | 1.9 | |

| Daily fruit | >5 services/400 g/day/capita | 6 | 2.3 |

| No, but occasionally | 260 | 97.7 | |

| Daily vegetable | At least five services/400 g/day | 66 | 24.8 |

| No, but occasionally | 200 | 75.2 | |

| Saturated oil | Saturated oil always | 263 | 98.9 |

| Clotted oil and animal butter | 3 | 1.1 | |

| Dietary diversity score | Low dietary diversity | 181 | 68 |

| Medium dietary diversity | 76 | 28.6 | |

High dietary diversity |

9 |

3.4 |

Table 2: Magnitude of lifestyle behaviors of middle aged urban residents of west Ethiopia 2019.

Lipid profiles and anthropometric measurements

Out of the 266 participants tested, 27.8%, 16.2%, 7.1%, 18.4% and 20.3% were found to have undiagnosed raised SBP, DBP, FBS, BP and raised triglycerides respectively. More than half (58.6%) of participants were found to have central obesity and 15.4% of participants had metabolic syndrome (Table 3).

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Categorical | Frequency | Percent% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 22.85 (3.68) | Normal | 131 | 49.2 |

| Overweight | 52 | 19.5 | ||

| Obese | 65 | 24.4 | ||

| Chronic energy deficiency | 18 | 6.8 | ||

| Central obesity | 85.39 (8.37) | Yes | 156 | 58.6 |

| No | 110 | 41.4 | ||

| High hip circumference | 93.49 (9.05) | Yes | 192 | 72.2 |

| No | 74 | 27.8 | ||

| Raised systolic BP ≥ 130 | 120.02 (14.24) | Yes | 74 | 27.8 |

| No | 192 | 72.2 | ||

| Raised diastolic BP ≥ 85 | 77.11 (8.98) | Yes | 43 | 16.2 |

| No | 223 | 83.8 | ||

| Raised BP ≥ 130/85 mmHg | - | Yes | 49 | 18.4 |

| No | 217 | 81.6 | ||

| Raised FBS ≥ 100 mg/dl | 99.70 (29.60) | Yes | 19 | 7.1 |

| No | 247 | 92.9 | ||

| Raised TG level ≥ 150 mg/dl | 131.63 (24.92) | Yes | 54 | 20.3 |

| No | 212 | 79.7 | ||

| Reduced HDL <40 for M <50 for F | 52.01 (10.34) | Yes | 52 | 19.5 |

| No | 214 | 80.5 | ||

| Had metabolic syndrome | - | Yes | 41 | 15.4 |

| No | 225 | 84.6 |

Table 3: Mean and frequency distribution of lipid profiles and anthropometric of adults, 2019.

Self-reported health related quality of life

Sixty five (24.4%) respondents live poor life and highest percentage of them complain for pain or discomfort (15.04%) followed by anxiety or depression (14.29%) (Table 4).

| EQ-5D | Degree of problem | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility | Normal | 249 | 93.6 |

| Partially | 17 | 6.4 | |

| Severely | - | ||

| Usual activity | Normal | 253 | 95.1 |

| Partially | 12 | 4.5 | |

| Severely | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Self care | Normal | 264 | 99.2 |

| Partially | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Severely | - | ||

| Pain or discomfort | Normal | 226 | 85 |

| Partially | 40 | 15 | |

| Severely | - | ||

| Anxiety or depression | Normal | 228 | 85.7 |

| Partially | 38 | 14.3 | |

| Severely | - | ||

| HRQoL | Good HRQoL | 201 | 75.6 |

| Poor (had ≥ 1 of 5D) | 65 | 24.4 |

Note: EQ-5D: EuroQoL 5-dimensions; HRQoL: Health Related Quality of Life

Table 4: Responses to element of the EQ-5D with degree of problems among adults, 2019.

Metabolic syndrome and associated factors

Findings showed that on bivariate analysis from EQ-5D index only mobility problem and anxiety/depression were significantly associated with metabolic syndrome. Association was found between EuroQol-5dimensions and metabolic syndrome. Among adults had poor health quality the risk of metabolic syndrome was increased? Individuals having mobility difficulty showed significant association (P=0.003) and odds difficult in mobility was more than 4 times (OR=4.42; 95% CI: 1.58, 12.42; P, 0.005) higher than healthier once. Likewise, having anxiety/depression had increased risk of metabolic syndrome (OR=1.81; 95% CI 1.30, 2.21; P, 0.068).

On multivariable logistic analysis, mobility problem and depression were significantly associated. Being having mobility problem (AOR=7.53; 95% CI 2.00-12.70) was significantly and positively associated with the condition of being metabolic syndrome. Similarly metabolic risk was increased among depressed population, having metabolic syndrome likely in depressed respondents after adjustment (AOR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.13-1.65), though statistically not significant (p=0.233). In summative assessment this study demonstrated that HRQoL was showed significant positive association with metabolic syndrome. Undiagnosed metabolic syndrome was associated with health related quality of life and found to be statistically significant (P<0.009) (Figure 1 and Table 5).

| Variables | Categories | Metabolic syndrome | cOR (95% CI) | p-value | aOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||||

| Age | 41-48 years | 22 | 123 | 0.65 (0.25, 1.53) | 0.324 | 0.45 (0.02, 9.24) | 0.602 |

| 49-56 years | 8 | 69 | 1.86 (1.82, 4.23) | 0.136 | 12.74 (1.40, 41.49) | 0.015 | |

| 57-64 years | 11 | 33 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| Physical activity | Low | 36 | 206 | 2.54 (2.15, 8.47) | 0.027 | 0.75 (0.09, 6.44) | 0.792 |

| Vigorous | 3 | 8 | 1.22 (1.04, 4.89) | 0.96 | 7.78 (0.37, 16.63) | 0.19 | |

| Moderate | 2 | 11 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| High BMI (kg/m2) | Normal | 3 | 128 | 5.57 (1.43, 23.17) | 0.018 | 2.01 (3.61, 11.23) | 0.001 |

| Overweight/Obese | 38 | 79 | 41.37 (11.93, 143.5) | 0.0001 | 25.67 (7.18, 94.59) | 0.0001 | |

| Chronic energy def | 1 | 17 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| High SBP (yes>/no<) | >130 mmHg | 22 | 49 | 0.24 (0.12, 0.48) | 0.0001 | 9.30 (1.12, 77.37) | 0.039 |

| <130 mmHg | 19 | 176 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| High DBP (yes>/no<) | >85 mmHg | 13 | 29 | 0.32 (0.15, 0.69) | 0.003 | 1.54 (1.19, 12.73) | 0.688 |

| <85 mmHg | 28 | 196 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| High FBS (mg/dl) | ≥ 100 | 14 | 5 | 0.04 (0.02, 0.13) | 0.0001 | 4.42 (1.91, 10.25) | 0.001 |

| <100 | 27 | 220 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| Raised | ≥ 150 mg/dl | 37 | 17 | 113.18 (36.05, 355.29) | 0.0001 | 0.014 (0.003, 0.063) | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides | <150 mg/dl | 4 | 208 | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| HDL-cholesterol | Yes (F<50 and M<40) | 22 | 12 | 22.30 (9.98, 49.82) | 0.0001 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.13) | 0.001 |

| No | 29 | 203 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| Mobility problem | Yes | 7 | 10 | 4.42 (1.58, 12.42) | 0.005 | 7.53 (2.00, 12.70) | 0.003 |

| No | 34 | 215 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

| Anxiety/Depression | Yes | 5 | 33 | 1.81 (1.30, 2.21) | 0.068 | 1.46 (1.13, 1.65) | 0.233 |

| No | 36 | 192 | 1 | - | 1 | - | |

Note: p<0.05 significant association

Table 5: Multivariate analysis of metabolic syndrome associated factors, urban residents, west Ethiopia, 2019.

This study was not limited, but also assesses related associated factors. Accordingly, on bivariate analysis age, low physical activity, BMI, blood pressure, high fasting, triglyceride and cholesterol were risk factors. We found metabolic risk would increased by 86% (OR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.82-4.23) for participants aged 49-56 years. Regarding triglycerides level the current study demonstrated that those who had risen were found to have high metabolic syndrome than others (OR: 113.18 CI=36.05-355.29). Regarding the topic of BMI, our study revealed those participants who had overweight/obese had 41.37 (OR: 41.37, CI: 11.93, 143.51) times higher chance of having metabolic syndrome than normal range of BMI.

On multinomial logistic analysis age, BMI, high blood pressure and HDL-cholesterol showed association for metabolic syndrome, but not significant with diastolic blood pressure (p=0.688). The developing metabolic risk was about nine times higher in those with systolic blood pressure of ≥ 130 mm Hg (AOR: 9.30; 95% CI 1.12-77.37; P, 0.039). Similarly, FBS ≥ 100 mg/dl was found to increase metabolic syndrome risk by more than fourfold (AOR: 4.42; 95% CI 1.91, 10.25; P<0.001). Finally, high BMI and age between 49-56 years were associated with more than twenty five and twelve times developing (AOR: 25.67; 95% CI 7.18, 94.59; p<0.0001) and (AOR:12.74; 95% CI 1.40, 41.49; p, 0.015) respectively.

Discussion

The study reveals unscreened metabolic syndrome and its association among urban residents of west Ethiopia. It demonstrated that high ORs of metabolic syndrome increased with its component factors and by using EQ-5D; both ORs and AOR increased with presence of mobility problem.

Undiagnosed metabolic syndrome and its component like raised triglyceride, hypertension and raised fasting blood sugar were 15.4, 20.3, 18.4 and 7.1% respectively. From the participants had metabolic syndrome, 67.69% of them were females and of those had poorer, adults’ aged 41-48 years accounts 50.77%. Other studies result demonstrated that the prevalence was significantly higher in the middle aged and sky rocket in middle age and typically declines in the elderly.

The prevalence of undiagnosed FBS ≥ 100 mg/dl (7.1%) was less comparatively with pooled results of urban areas of Sudan (7.7%), urban Egypt (20%) and red delta river of middle-aged Vietnam (40%). Since, undiagnosed metabolic syndrome were not conducted on healthier in different urban areas of Ethiopia we compare it with data of other countries. Study conducted in north Indian, prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 32.5% which is higher than this finding.

Worldwide, one in four (23%) of adults do not currently meet the global recommendations for physical activity which was less compared to this study (91.0%). This result was highly prevalent. We found physical inactivity was associated with metabolic syndrome, this confirms the study done in other country.

Waist circumference is a measure of central obesity as per IDF as well as ATP-III criteria and Sinaga et al. Based on the cut off points, this study reveals 58.6% of adults have high waist circumference which have nearly similar result with study conducted on Jimma university workers (58.9%). The mean ± SD of central obesity (85.39 ± 8.37) of our study result was higher than this cut of point but lower than German firefighters (89.9 ± 10.0) and office workers (97.3 ± 11.7).

On EQ-5D index, community health quality status measured among middle aged adults, Nekemte, in 2019. Pain/ discomfort (15%), anxiety/depression (14.3%) and mobility problem (6.4%) found. Confirming that study conducted in Tehran, pain/discomfort (34.4%) and anxiety/depression 33.4% were why the people suffered for.

The findings demonstrated from EQ-5D, participants with difficulty in mobility and anxiety/depression were showed high significant association with patients of metabolic syndrome. In general, undiagnosed metabolic syndrome and HRQoL showed significant positive association with statistically significant (P<0.009). Similar to this finding, degenerative like: Hypertension diabetes and coronary heart disease associated significant and also in Iran. This study adds message for public health to stress on community based diagnosis of NCD, dose of sodium diet intake, fruit and vegetable consumption and others food groups by community. Approximately, all participants consume greater than a teaspoon (>6 g/day) of salt a day, 58.6% of them had central obesity and 18.4% elevated blood pressure. These findings confirm with other studies, elevated blood pressure and central area obesity related to high-sodium diet. Also majority (97.7% and 75.2%) of the respondents occasionally or not at all consume fruit and vegetables respectively. Dietary guidelines also consider ethnic backgrounds, since Ethiopian did not have dietary guidelines, so it needs other formulation to define their association.

Conclusion

Unscreened metabolic syndrome status and poor health related quality of life in urban residents of west Ethiopia was 15.4% and 24.4% respectively. By using EQ-5D: Mobility problem, pain/discomfort and depression/anxiety showed major health complain. Association found between the variables. Therefore, to reduce the magnitude, curb NCD and improve quality of life among adults, it is recommended: Applying holistic lifestyle intervention approach, launching health and nutrition information system or community-based service delivery system and active screening for early detection of risk factors would bring significant changes. To sum up, establishing healthy lifestyles training, diet therapy and NCD prevention center is crucial for awareness creation, capacity building, rehabilitation and job creation at all.

Limitations of the Study

The study is subject to recall bias because of the cress sectional nature and unhealthy lifestyles practices were hidden by respondents due to socially unacceptable behaviors and quality of life were self-reported which might under or overestimate the actual levels of risk factors. Any other bottle neck was insufficient biochemical to take large study population.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Jimma university (Approval No. IHRPGD/596/2019; January 1, 2019). Support letter was also taken from all concerned bodies. Prior to the first interview, participants were informed about objectives of the study and privacy during the interview. Written consent was also obtained from individual participants.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Disclosure

We declare that there is no competing interest.

Funding

The authors were not received financial support for the publication, but fund for facilitating data collection allocated by Jimma university.

Author Contributions

All made substantial to conception from proposal construction, data collection and manuscript writing to final approval of the version to be published.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants, professionals, Nekemte health bureau, Wollega university specialized hospital, Cheleleki clinic and administrative of Nekemte municipal.

References

- Sommer I, Griebler U, Mahlknecht P, Thaler K, Bouskill K, Gartlehner G, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in non-communicable diseases and their risk factors: An overview of systematic reviews. BMC Publ Health. 2015;15:1-2.

- Friel S, Chopra M, Satcher D. Unequal weight: Equity oriented policy responses to the global obesity epidemic. BMJ. 2007;335:1241-1243.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popkin BM. Does global obesity represent a global public health challenge. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:232-233.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samuelson G. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. J Scand Natr. 2004;48:56-57.

- Abdulkadir J, Reja A. Management of diabetes mellitus: Coping with limited facilities. Ethiop Med J. 2001;39:349-365.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gebre MW. Diabetes mellitus and associated diseases from Ethiopian perspective: Systematic review. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2013;27:249-253.

- Zhang Y, Ma D, Cui R, Hilawe EH, Chiang C, Hirakawa Y, et al. Facilitators and barriers of adopting healthy lifestyle in rural China: A qualitative analysis through social capital perspectives. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2016;78:162-163.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American heart association/national heart, lung and blood institute scientific statement. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2005;112:2735-2752.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kularatna S, Whitty JA, Johnson NW, Jayasinghe R, Scuffham PA. EQ-5D-3L derived population norms for health related quality of life in Sri Lanka. PloS One. 2014;9:108434.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steyn NP, Mchiza ZJ. Obesity and the nutrition transition in sub‐Saharan Africa. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1311:88-101.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mattei J, Malik V, Wedick NM, Campos H, Spiegelman D, Willett W, et al. Symposium and workshop report from the global nutrition and epidemiologic transition initiative: Nutrition transition and the global burden of type 2 diabetes. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:1325-1335.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vogl M, Wenig CM, Leidl R, Pokhrel S. Smoking and health-related quality of life in English general population: Implications for economic evaluations. BMC J Publ Health. 2012;12:1-0.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saffari M, Koenig HG, Pakpour AH, Sehlo MG. Health related quality of life among military personnel: What socio-demographic factors are important. Appl Res Qual. 2015;10:63-76.

- Kreimeier S, Oppe M, Ramos-Goni JM, Cole A, Devlin N, Herdman M, et al. Valuation of EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, youth version (EQ-5D-Y) and EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) health states: The impact of wording and perspective. Value Health. 2018;21:1291-1298.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tefera G. Determinants of proteinuria among type 2 diabetic patients at Shakiso health center, southern Ethiopia: A retrospective study. Adv Diabetes Metab. 2014;2:48-54

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belachew T, Hadley C, Lindstrom D, Getachew Y, Duchateau L, Kolsteren P. Food insecurity and age at menarche among adolescent girls in Jimma zone Southwest Ethiopia: A longitudinal study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:1-8.

- Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolds K, McGinn AP, Rajpathak S, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic risk factor clustering: prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999-2004). Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1617-1624.

- Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS, Vasan RS, Nathan DM, Sullivan LM, et al. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2906-2912.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Long DM, de Long ER, Wood PD, Lippel K, Rifkind BM. A comparison of methods for the estimation of plasma low-and very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: The lipid research clinics prevalence study. Jama. 1986;256:2372-2377.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. The Lancet. 2011;377:557-567.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.