Pediatric Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation Practices and Challenges in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Gulf Cooperation Council Countries

2 Department of Cardiac Sciences, Ministry of the National Guard—Health Affairs, King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Healt, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Received: 27-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. amhsr-24-150500; Editor assigned: 30-Sep-2024, Pre QC No. amhsr-24-150500 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Oct-2024 QC No. amhsr-24-150500 ; Revised: 21-Oct-2024, Manuscript No. amhsr-24-150500 (R); Published: 28-Nov-2024

Citation: AlJassim NA, et al. Pediatric Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) Practices and Challenges in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2024;14: 1075-1080.

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Introduction: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) is a vital rescue therapy for patients experiencing refractory heart or respiratory failure after conventional intervention failure. Establishing a new ECMO program, particularly for neonates and children, has challenges in logistics or operation. Furthermore, maintaining a standardized ECMO program add more complexity.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was distributed to health care professional in Saudi Arabia and the GCC to describe the pediatric ECMO experience, practices and challenges for potential expansion.

Results: A total of 254 responses were collected, 82% from Saudi Arabia. In these, 56% have ECMO service at their centers. Majority are working in Pediatric Intensive Care Units (PICUs), with >300 admissions per year, treating respiratory failure cases as top diagnosis. ECMO experience and practice was variable among respondents as well as in ECMO deployment and management with main findings: (1) Nearly 60% of respondents have no experience or limited exposure to ECMO during their training; (2) Pediatric ECMO is primarily used for cardiac cases in the region via central cannulation, with limited respiratory use reported and (3) Challenges in establishing ECMO include a lack of logistics, manpower and system support.

Conclusion: Despite the life saving role of ECMO in pediatrics, its availability is limited service and with many challenges. Enhanced pediatric ECMO training and system support are crucial for successful program initiation and development.

Keywords

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC); Extracorporeal Life-Support (ECLS); Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO); Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO); Intensive Care Unit (ICU); Kingdom of Saudi Arabia(KSA)

Introduction

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO) is an advanced extracorporeal support that provides circulatory and/or respiratory support until organ recovery. The first successful use of ECMO in a neonate was reported in 1975 and its application has expanded to include children and adults, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, with new centers being established successfully for adults in Saudi Arabia. According to the ELSO registry report in 2023, over 45,000 neonates and 29,000 children have received ECMO support, with overall survival rates exceeding 60% [1-3].

Despite the global growth, its implementation in the Southwest Asia and Africa (SWAAC) region, particularly for pediatrics, remains limited due to logistic and resource constraints [1]. To our knowledge, few pediatric ECMO centers exist in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries [4].

We did a web search about ECMO implementation in Saudi Arabia (SA) which revealed fifteen published papers. Ten studies are retrospective cohort studies, one case-control study and four were case reports or case series. The majority of included patients from cardiac units with ECMO utilized for cardiac support are about 3.4%-4% out of the total of open-heart surgeries [5-19]. Two case reports only reported using ECMO for respiratory support [8-10].

Materials and Methods

This study utilized a cross-sectional survey distributed to healthcare professionals in SA and GCC countries to assess the current practice, experience and potential challenges of expanding pediatric ECMOs. The survey was conducted using the SurveyMonkey platform and was promoted through social media platforms within professional healthcare groups and online scientific ECMO webinars. The survey was developed by pediatric intensivists who work at King Fahad Medical City (KFMC) in Riyadh which is a neonatal and pediatric ECMO center dealing with both cardiac and respiratory ECMO cases. Questions were developed to explore the current practice using ELSO guidelines and best practice advised. Other questions were also developed to address healthcare professionals' beliefs and presumed barriers to starting an ECMO program in the region. Closed-ended questions were predominantly used to standardize responses and few were multi-choice questions for questions that could have more than answers, like ECMO modalities and challenges. The survey’s questions were divided into four main domains:

Demographic information

Age, gender, profession and region of work

ICU settings

This domain captured ICU characteristics, including bed capacity, annual admissions and common diagnoses for ICU admissions. It also inquired about hospital type (governmental, private, or specialized) and nursing staff to patient ratio

ECMO experience and practice

This section covered the availability and types of ECMO services provided, including Veno-venous (VV-ECMO) and venoarterial (VA-ECMO) modalities, ECMO decision-making processes, cannulation techniques (central vs. peripheral access) and participant experience with ECMO.

Personal believes and perceived challenges in ECMO

This domain asked respondents about perceived barriers to ECMO implementation as multi-choice options and their beliefs about ECMO.

The study received exemption approval from the King Fahad Medical City (KFMC) Research Center Institutional Review Board (IRB No#24-399). Participation was voluntary and no incentives were offered.

Results

We received 254 responses to the survey. Table 1 shows demographic data of participants.

| General Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

Age |

|

| 25-34 years | 77 (30) |

| 35-44 years | 111 (44) |

| 45-54 years | 51 (20) |

| Above 54 years | 15 (6) |

Gender |

|

| Female | 135 (53) |

| Male | 119 (47) |

Profession |

|

| ICU Consultants | 41 (16) |

| ICU Assistant/Fellows | 35 (14) |

| Pediatric Intensivists | 76 (30) |

| Cardiologists | 8 (3) |

| ICU Nurses | 35 (14) |

| Respiratory therapists | 41 (16) |

| Others (Neonatologists, etc.) | 18 (7) |

ECMO service at their centers |

|

| Yes | 142 (56) |

| No | 112 (44) |

| Region of work | |

| KSA-Eastern | 25 (10) |

| KSA-Central | 127 (50) |

| KSA-Northern | 18 (7) |

| KSA-Western | 28 (11) |

| KSA-Southern | 15 (6) |

| UAE | 13 (5) |

| Kuwait | 8 (3) |

| Oman | 2 (1) |

| Other | 18 (7) |

Table 1: Demographics distribution of responders.

PICU setting

Most ICUs have more than 300 admissions per year with a patientto- nurse ratio of 2:1. 163 (64%) respondents are working in governmental hospitals, 29 (11.4%) in specialized hospitals, 27 (10.6%) in private hospitals and 35 (14%) respondents in other sectors. About 38.4% of respondents take care of pediatric patients in their ICUs, 23% have all age groups, 24.7% take care of neonates and 13.7% take care of adults only. Among PICUs, 69 (30.8%) of respondents have <10 beds, 71 (31.7%) have 11- 20 beds, 55 (24.6%) have 21-30 beds and 29 (12.9%) have >30 beds. The most frequent diagnosis on admission was respiratory failure followed by septic shock then heart failure.

Pediatric ECMO experience and practices

Of the respondents, 56% reported having ECMO services in their centers. Among ICUs that have ECMO, the survey results revealed that ECMO is offered for more than 5 years in 42.3%, 2-5 years in 19% and less than 2 years in 12.7%. Also, few respondents reported that their centers are planning to have ECMO (5.5%). ECMO run per year is less than 10 in majority of centers (63.7%), while 20% have 10-20 ECMO run per year and only 16.3% have >20 ECMO run annually.

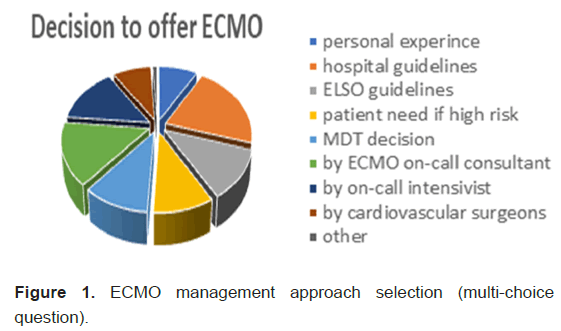

Survey revealed that 65% of the ICUs, offer VA-ECMO and about 35% offer VV-ECMO. Regarding ECMO Cannulation, majority do central ECMO cannulation (50%), while 32.2% do percutaneous cannulation and 17.7% they do peripheral cutdown ECMO cannulation. Variable ECMO systems are used in the region, too. About 94% were having clear policies and guidelines for ECMO. However, when we asked how the team decision process to offer ECMO in their ICUs, it was based on a different approach, mostly more than one way to support their decision, See (Figure 1).

The available ECMO experience among respondents who participated in the survey was about 40% with variable years of experience but the majority had less than 2 years of experience in pediatric ECMO; 19 (7.5%) respondents have VA-ECMO experience, 17 (6.7%) respondents have respondents VVECMO experience, 62 (24.45%) have experience in both VV and VA-ECMO. However, 76 (29.9%) of respondents have no experience on ECMO while 79 (30%) respondents have exposure to ECMO from training only.

ECMO believes and challenges

Most respondents believe the challenges are the lack of skilled human resources, logistical support and the high costs associated with running ECMO programs (Table 2). Despite challenges, the majority of responders support expanding pediatric ECMO services and they believe that ECMO is life saving service. Also, >65% of respondents believe that with the available resources in their ICUs it is convenient to start pediatric ECMO program.

| Description of pediatric ECMO service | N (%) |

| Life-saving | 170 (67) |

| Demanding | 61 (24) |

| Underestimated | 46 (18) |

| Overrated | 8 (3) |

| Neutral | 38 (15) |

| Challenges limiting ECMO centers | Respondents' belief (%) |

| Lack of human resources | 109 (43) |

| Lack of logistical and system support | 119 (47) |

| High running costs | 109 (43) |

| Lack of knowledge | 89 (35) |

| Service is unnecessary | 20 (<10) |

Table 2: The respondents' perspectives and perceived challenges.

Discussion

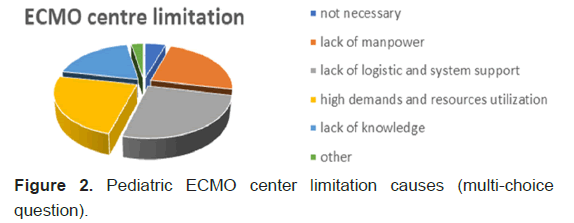

Our survey provides valuable insights into the current state of pediatric ECMO practices in Saudi Arabia and the GCC countries. It highlighted the presence of variable experiences and practices in pediatric ECMO with three main findings; first, 30% of respondents had no ECMO experience, with a similar proportion reported for a limited exposure during their training program. The rest have experience with pediatric ECMO with most having less than two years of experience. This finding aligns with the presence of fewer pediatric ECMO programs in the region, as shown in the SWAAC ELSO registry. Second, the survey confirmed that ECMO is offered for cardiac cases and using central cannulation approach mostly. This is reflected in previous studies in Saudi Arabia which included mainly ECMO post cardiectomy in PCICUs. On the other hand, VVECMO for respiratory and percutaneous cannulation approach seems limited as reported in this survey by almost one third of respondents, despite reporting the respiratory failure as the top admitting diagnoses in their PICUs [6-12,14-19]. Interestingly, the majority of those who have ECMO programs reported that it is offered for less than 5 years and that they have less than 10 cases each year. When we asked in the survey why there are limited pediatric ECMO centers in the region, most participants believed that the following were the top reasons: Lack of logistics and system support, lack of manpower and the high demands of ECMO programs and resource utilization. Many growing pediatric ECMO programs internationally including SWAAC region. This highlight the need to develop and support the new programs and increase the knowledge among intensivists to expand the respiratory ECMO support services for neonates and children [1]. In the survey, we also highlighted the challenges to develop pediatric ECMO program from respondents' perspective which are shown in Table 2. Despite all, many respondents believe that ECMO is still can be offered with the available resources in their centers which is encouraging further support.

In fact, pediatric ECMO is resource-intensive which need high specialized skills by many stakeholders in ECMO deployment and it is complex in management, too. Literature indicates that centers with higher ECMO case volumes and longer ECMO experience tend to have better outcomes despite high resources use. High volume of cases lead to repeated exposure that strengthen team members’ skills and improves decision-making during ECMO management which enhance program development [20]. Low volume programs and less established ECMO services or low volume ECMO programs, staff may suffer from limited exposure and slower experience development which can impact negatively on the ECMO program and affect confidence levels in critical situations which lead to thinking of more of improving access to centralization of ECMO. However, ECMO case volume related outcome was different in other studies [20]. A recent paper published by Ertugrul et al on 2024 illustrated comparable outcome between low-volume and high volume centers of ECMO in Australia and New Zealand as there was no difference in death or disability at six months between them, possibly due to the training and having other model of coordinated care that includes patient transfers between centers [21,22]. Therefore, low volume centers are equally important as long as they have a designated team to assist in the patient selection process and management based on present ELSO guidelines and continuous training. Importantly, having a structured ECMO training programs, including simulation-based and clinical training modules, are essential together with experienced pediatric ECMO team [23-28]. Expanding partnerships with big pediatric ECMO centers and international organizations like ELSO and other ECMO centers may also support the development of recently established programs and standardize the training [23,24].

Frameworks and patient management that can be adapted to local needs in Saudi Arabia and the GCC countries. Thus, could also help in addressing the gaps and challenges found in this survey including expanding the use of ECMO as respiratory support.

The participants in the survey also reported a wide variability in cannulation techniques that could be related to patient’s age or the available staff experience (surgeons vs intensivists) and variable ECMO management approaches as well which shows the need for standardization. Although the predominance of big cardiac centers in the region lead to more cannulation by with the surgeons transthoracic (central) cannulation approach. Nowadays, the available skills of ultrasonography guided line insertion among pediatric intensivists increasing the practice of percutaneous cannulation for pediatric ECMO and even neonates which need further awareness, training courses and competency [5,29,30].

Many ECMO centers and institutions internationally are facing significant challenges in setting up or maintaining ECMO programs. ECMO is costly and fewer centers exist in the SWAAC region than in Europe and the United States, as noted by Ponaam and Tiwari. From our survey, ECMO implementation in Saudi Arabia and GCC countries is also hampered by lack of logistics and system support as well as shortage of specialized personnel, particularly perfusionists. Support is required from the institution infrastructure and the system to facilitate developing and expanding the ECMO program and address any challenges [31,32]. A great example was Saudi Arabia when the Saudi Ministry of Health in 2021 laid the groundwork for expanding services across the country for adult ECMO and successfully implemented a national ECMO program with standard policy and process.

This initiative included a hotline for ECMO consultations and retrievals and has the potential to bridge gaps in care by facilitating the transfer of critically ill patients after ECMO deployment to an equipped ECMO center. Also, the National ECMO program in KSA established new ECMO centers during the pandemic, which was later supported in the ECMO literature. However, ongoing efforts are still needed to ensure that the necessary training and resources are available for longterm sustainability [3]. Similar challenges could be seen in the region for pediatric ECMO despite differences and complexity in cannulation and ECMO management. This survey reveals that the key barriers to expanding ECMO services-human resources, logistical challenges and available training require immediate attention from both healthcare institutions and policymakers (Figure 2). However, lack of human resources and availability of ECMO specialized personnel, particularly perfusionists was reported most which can be overcome by more training of ECMO specialists [33]. Providing pediatric ECMO centralization and efficient transport system could help regions that have limited ECMO center access to improve equity of care provided pending time for further improvement [34].

Conclusion

ECMO support is life saving and should be offed to any child with refractory respiratory or cardiac failure. Targeted training programs, ECMO specialists training, resource allocation and system support are essential to expand pediatric ECMO services in Saudi Arabia and GCC countries, we believe Furthermore, increasing awareness among intensivist, standardizing ECMO protocols and guidelines across the centers could enhance outcomes while developing from low volume to higher volume ECMO center overnight.

Limitations

The limitations of this survey include potential selection bias, as distribution is not equal across different stakeholders and clinicians with a strong interest in ECMO were more likely to be motivated and support developing ECMO, skewing results. The online format and distribution via social media may have restricted access to certain professional groups or ICUs across the region especially GCC countries, which is limiting the survey’s reach. Also, limitation in the survey design of questions as we did not differentiate between those working in ECMO centers from others and having experience vs none. Future research should consider longitudinal studies to track changes in ECMO practices and resources. Also, review of data from ELSO in retrospective to assess the programs in comparison to other regions is encouraging.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank all the participants who spent time to answer this survey. We would also like to thank the Saudi Society of Critical Care secretary for sharing the survey and KFMC pediatric ECMO committee members.

Author Contributions

Dr. Nada aljassim, Dr. Nooralhuda; IRB (Institutional Review Board) development

Dr. Nada aljassim, Dr. Nabeel Almashraqi; survey questionnaire development.

Dr. Nada Aljassim, Dr. Nooralhuda; literature review and writing the manuscript.

Dr. Mohamed Kabbani; manuscript revision.

References

- ECLS Registry report international summary. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). 2023.

- Burch R, Poynter J. The first case reported ECMO. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 1975;10:679-684.

- Adult KSA. Annual Report on Adult ECMO Services in Saudi Arabia. Riyadh: Ministry of Health. 2021

- Pooboni SK. ECMO in India, SWAAC ELSO: Challenges and solutions. Indian Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2021;37:S344–S350.

- AlKhalifah AS, AlJassim NA. Venovenous extra corporeal life support in an infant with foreign body aspiration: A case report. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports. 2022;37:101636.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baslaim G, Bashore J, Al-Malki F, Jamjoom A. Can the outcome of pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after cardiac surgery be predicted? Annals of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2006;12:21.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Soufi S, Buscher H, Nguyen ND, Rycus P, Nair P. Lack of association between body weight and mortality in patients on veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intensive care medicine. 2013;39:1995-2002.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen G, Al-Ata J, Alkhushi N, Bahaidarah S, Baho H, et al. Cardiac catheterization during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after congenital cardiac surgery: A multi-center retrospective study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2022;43:92-103.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elella RA, Habib E, Mokrusova P, Joseph P, Aldalaty H, et al. Incidence and outcome of acute kidney injury by the pRIFLE criteria for children receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after heart surgery. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2017;37:201-6.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alsoufi B, Awan A, Manlhiot C, Al-Halees Z, Al-Ahmadi M, et al. Does single ventricle physiology affect survival of children requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support following cardiac surgery? World Journal for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery. 2014;5:7-15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parker NM, Zuhdi M, Kouatli A, Baslaim G. Late presenters with dextro‐transposition of great arteries and intact ventricular septum: to train or not to train the left ventricle for arterial switch operation?. Congenital Heart Disease. 2009;4:424-32.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baslaim GM, Jamjoom AA. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support post‐arterial switch procedure for a child with cystic fibrosis: Case report. Journal of Cardiac Surgery. 2006;21:419-20.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaath GA, Jijeh AM, Ismail SR, Hijazi O, Sulaiman RA, et al. Predictors of reopening the sternum in children after cardiac surgery. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2020;21:235-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ElMahrouk AF, Ismail MF, Hamouda T, Shaikh R, Mahmoud A, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in postcardiotomy pediatric patients 15 years of experience outside Europe and North America. The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 2019;67:028-36.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alamri RM, Dohain AM, Arafat AA, Elmahrouk AF, Ghunaim AH, et al. Surgical repair for persistent truncus arteriosus in neonates and older children. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2020;15:1-7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elassal AA, Al-Radi OO, Debis RS, Zaher ZF, Abdelmohsen GA, et al. Neonatal congenital heart surgery: contemporary outcomes and risk profile. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2022;17:80.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dohain AM, Abdelmohsen G, Elassal AA, ElMahrouk AF, Al-Radi OO. Factors affecting the outcome of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation following paediatric cardiac surgery. Cardiology in the Young. 2019;29:1501-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aljassim N, Almashraki N, Tageldein M. Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenator (ECMO) for complicated patients with D-Transposition of the Great Arteries (D-TGA): A single center experience. 10th SWAACE Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (SWAAC ELSO) 2024 conference abstracts, Kuwait City, Kuwait. February 15th–17th, 2024. ASAIO Journal. 2024.

- Aljassim N, Tageldein M, Almashraki N, Safi M, Al Tamimi O. Veno arterial extra corporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge of pulmonary hypertension management post open heart surgery: A case series and literature review. Saudi Critical Care Journal. 2022;6:S14-7.

- Verma A, Hadaya J, Williamson C, Kronen E, Sakowitz S, et al. A contemporary analysis of the volume–outcome relationship for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the United States. Surgery. 2023;173:1405-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng PY, Ip A, Fang S, Lin JC, Ling L, et al. Effect of hospital case volume on clinical outcomes of patients requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A territory-wide longitudinal observational study. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2022;14:1802.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ertugrul AD, Neto AS, Fulcher BJ, Charles-Nelson A, Bailey M, et al. Hospital-level volume in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and death or disability at 6 months. Critical Care and Resuscitation. 2024.

- Cicalese E, Meisler S, Kitchin M, Zhang M, Verma S, et al. Developing a new pediatric extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) program. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2023;51:697-703.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ELSO. ELSO guidelines for ECMO centers. 2014.

- ELSO. ELSO guidelines for ECMO. 2023

- MacLaren G. Extracorporeal Life Support: The ELSO Red Book. 6th Edition. 2021.

- Maratta C, Potera RM, Van Leeuwen G, Moya AC, Raman L, et al. Extracorporeal life support organization (ELSO): 2020 pediatric respiratory ELSO guideline. ASAIO Journal. 2020;66:975-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McMichael AB, Ryerson LM, Ratano D, Fan E, Faraoni D, et al. 2021 ELSO adult and pediatric anticoagulation guidelines. ASAIO Journal. 2022;68:303-10.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nanjayya VB. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO).

- HERMON MM, Golej J, Mostafa G, Burda G, Vargha R, et al. Veno-venous two-site cannulation versus veno-venous double lumen ECMO: Complications and survival in infants with respiratory failure. Signa vitae: Journal for intesive care and emergency medicine. 2012;7:40-6. [Crossref]

- Ponaam J, Tiwari M. Rapid development and implementation of an ECMO program. Medical and Surgical Critical Care. 2021;25:99-104.

- Ranjan R, Kakkar A. Establishing an ECMO program in a developing country: Challenges and lessons learned. Journal of Critical Care. 2019;54:1-7.

- ELSO. ELSO guidelines for training and continuing education of ecmo specialists. 2010.

- Brodie D, Abrams D. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation during respiratory pandemics: Past, present and future. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2022;205:1382–1390.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.