The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Neurosurgery Residents’ Psychological Consequences

Received: 09-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-101901; Editor assigned: 12-Jun-2023, Pre QC No. AMHSR-23-101901 (PQ); Reviewed: 27-Jun-2023 QC No. AMHSR-23-101901; Revised: 09-Dec-2023, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-101901 (R); Published: 16-Dec-2023

Citation: Aminmansour B, et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Neurosurgery Residents Psychological Consequences. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2023;13:890-895

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Introduction: The world is currently facing an unprecedented pandemic crisis. This study focuses on assessing the psychological consequences of the neurosurgery residents’ during COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods: Residents attending first to th e fifths yea r in the medical universities were invited to participate. The fearfulness scale, generalized anxiety disorder, center for epidemiologic studies depression scale, sleep disturbances, psychological discomfort and acute stress disorder scale were provided.

Results: The results of the analysis show a prevalence of symptoms such as psychological discomfort, acute stress disorder, sleep disturbances, and fear across the neurosurgery residents. 85 (68%) of the participants reported to suffer from high levels of psychological discomfort and 84 (67.2%) reported to suffer from high levels of acute stress disorder. 34 (27.2%) of the neurosurgery residents reported low levels, GAD symptoms. 121 (96.8%) of the participants reported, to suffer from moderate to high levels of fear. It looks similar for sleep disturbances with 119 (95.2%) of the participants indicated moderate to high levels.

Conclusion: More health promoting and mental disorder-preventing programs with high quality effectiveness studies are necessary. An integration of such programs into curricula would allow for greater utilization and could give greater emphasis to and prioritize mental health in medical education.

Keywords

COVID-19; Neurosurgery; Resident; Psychological consequences; Mental disorder

Introduction

COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) is a highly infectious disease with a long incubation period which was caused by SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) [1,2]. The pandemic scale of this novel Coronavirus has led to the world’s biggest public health crisis in over one hundred years and thus opened many unresolved issues [3]. The uncertainty and low predictability of COVID-19 not only threaten people’s physical health, but also affect people’s mental health, especially in terms of emotions and cognition, as many theories indicate [4,5]. These behavioral changes, both at the individual and community levels, appear to have been driven by the goal of disease avoidance [6,7].

According to Behavioral Immune System (BIS) theory [8] BIS is a motivational system with the goal of disease avoidance. It estimates the presence of pathogens from perceptual cues in the environment and elicits relevant emotional and cognitive responses. Such responses induce avoidance behavior in a pathogenic environment. This sequence of psychological responses, by preventing contact with and penetration into the body of these infectious sources, compensates for the physiological immune system which can sometimes be physically high cost. The theory of BIS has an evolutionary psychological basis, and it has been used to explain and predict a wide range of human behaviors. Additionally, the description of detailed mechanisms for disease avoidance redefined the adaptive value of disgust, which is a key emotion in BIS [9-11].

Since psychological changes caused by public health emergencies can be reflected directly in emotions and cognition, we can monitor psychological changes in time through emotional (e.g., negative emotions and positive emotions) and cognitive indicators (e.g., social risk judgment and life satisfaction) [12,14].

By assessing the crisis from a psychological perspective, in the field of applied psychology, it will help to delineate an actual picture of the human psychology in the twenty-first century during an extreme and unfamiliar situation and will help to better understand how a pandemic crisis [15-17].

The study identifies and analyzes psychological consequences of the corona crisis, especially examining psychological outcomes, as well as personal and social effects on neurosurgery residents’ mental health.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional online survey included neurosurgery residents (who completely filled out the questionnaires).

The subjects were selected according to the principle of stratified available sample. A total of 125 residents were selected from six universities of medical sciences in Isfahan, Tehran, Mashhad, Shiraz, Tabriz, and Mazandaran, and were then included in the study.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: Residents who were studying at universities inside Iran during the COVID-19 pandemic and who consented to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were residents who were not in residency during the COVID-19 pandemic and those who did not consent to participate in the study.

During the research process, informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. The invited participants were voluntary, and were guaranteed confidentiality. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Measures

The participants received a short description of the study before starting the questionnaire.

The prevalence of threat caused by COVID-19 was assessed with the 4 items fearfulness scale proposed by Duhachek. The items were displayed on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (does apply at all).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) with regard to COVID-19 was measured with the Farsi version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). This validated scale is widely used in the Iranian culture. It is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (almost every day) with seven items evaluating the frequency of anxiety symptoms over the past 8 weeks [18].

To assess depressive symptoms and moods connected to COVID-19 over the past 8 weeks the Farsi version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) was used. The original version was validated and used in different scientific areas to assess the occurrence of these symptoms. The participants had to indicate on a 4-point Likert-type scale whether the symptoms are prevalent (1 never or rarely; 4 usually or always) [19].

To examine the sleep disturbances associated with COVID-19, the Farsi version of the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) scale was used. PSQI is a widely used scale developed by Buysse et al., to evaluate the participants’ sleep disorder [20].

In this case, the participants had to indicate their sleep quality over the past 8 weeks. The participants were asked to report sleep disturbing incidents, their sleep quality, their usual sleep time, duration of sleep, use of medication to induce sleep as well as latency to fall asleep and tiredness during the day.

Psychological discomfort associated with the corona crisis was measured by the 6-item cognitive dissonance scale. Participants assessed if they experienced a state of psychological tension during the corona crisis on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranged from 1 (does not apply at all) to 5 (does apply at all). The Acute Stress Disorder Scale (ASDS) is a self-report inventory that (a) indexes Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) and (b) Predicts Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The ASDS is a 19-item inventory that is based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV, American psychiatric association, 1994) criteria.

Higher mean scores of the constructs presented above reflect a prevalence of those symptoms. Thus, the higher the score is, the more often they occur and the more severe they are.

We made the length of the survey short enough to not take more than 10 minutes to ensure a high completion rate.

Data were described by descriptive statistics-categorical variables were reported as percentages (%) and frequencies (n), while means and Standard Deviation (SD) were calculated for numerical ones. The difference between the groups was analyzed using Chi-square test. The correlation between independent and outcome variables and presented with Odds Ratio (OR) and Confidence Intervals (CIs).

The level of statistical significance in all used analyses was set at p<0.05. Data were processed using the statistical package IBM SPSS V.24.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

All the residents were men. The mean age was 30.31 years. Most of the respondents were in the second year, 42 (33.6%), and the main characteristics are illustrated in Table 1.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, (mean ± SD) | 30.31 ± 2.65 |

| First year | 35 (28) |

| Second year | 42 (33.6) |

| Third year | 27 (21.6) |

| Fourth year | 14 (11.2) |

| Fifth year | 7 (5.6) |

Table 1: Characteristics of respondents (N=125).

For the whole sample, the degree of fear was high (M=13.71, SD=2.47, range 8–20, 121 (96.8%) scoring ≥ 7.5) without significant differences between age and academic year (Table 2).

For the whole sample, the degree of GAD was low (M=8.14, SD=3.34, range 1–15, 34 (27.2%) scoring ≥ 10.5) without significant differences between age and academic year (Table 2).

For the whole sample, the degree of depressive symptoms was medium (M=30.49, SD=7.07, range 12-44, 59 (47.2%) scoring ≥ 30) without significant differences between Age and Academic year (Table 2).

For the whole sample, the degree of PSQI was medium-to-high (M=12.93, SD = 8.91, range 9-45, 119 (95.2%) scoring ≥ 10.5) without significant differences between age and academic year (Table 2).

For the whole sample, the degree of psychological discomfort was high (M=29.74, SD=4.01, range 3-21, 85 (68%) scoring ≥ 12) without significant differences between academic year, but significant differences between age (Table 2).

For the whole sample, the degree of ASDS was high (M=62.39, SD=12.28, range 37-78, 84 (67.2%) scoring ≥ 56) without significant differences between age and academic year (Table 2).

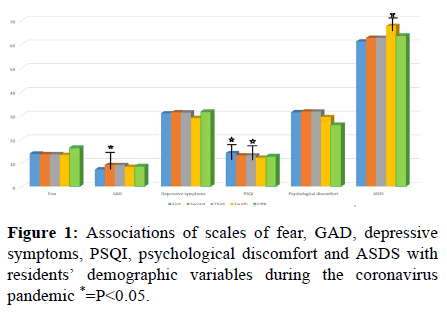

Distribution of fear, GAD, depressive symptoms, PSQI, psychological discomfort and ASDS, as well as their differences in relation to resident’s demographic variables.

| Variable | Age | Academic year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 (n=74) | ≥ 30 (n=51) | First year (n=35) | Second year (n=42) | Third year (n=27) | Fourth year (n=14) | Fifth year (n=7) | |

| Fear | 13.8 ± 2.5 | 13.5 ± 2.4 | 13.8 ± 2.5 | 13.5 ± 2.4 | 13.3 ± 2.3 | 13.2 ± 1.8 | 16.2 ± 2.7 |

| P-value | 0.543 | 0.59 | |||||

| GAD | 8.09 ± 3.3 | 8.2 ± 3.2 | 7.1 ± 3.4 | 9 ± 3.4 | 7.9 ± 2.7 | 8.2 ± 2.8 | 8.4 ± 4.4 |

| P-value | 0.843 | 0.181 | |||||

| Depressive symptoms | 31 ± 7.1 | 29.7 ± 7 | 30.7 ± 6.6 | 31.1 ± 7.3 | 29.8 ± 7.7 | 28.8 ± 6.8 | 31.4 ± 6.2 |

| P-value | 0.339 | 0.833 | |||||

| PSQI | 13.2 ± 4.2 | 12.4 ± 3.7 | 14 ± 3.5 | 13 ± 4.1 | 11.8 ± 4.5 | 12 ± 3 | 12.7 ± 4.5 |

| P-value | 0.264 | 0.259 | |||||

| Psychological discomfort | 27.7 ± 8.9 | 31.2 ± 8.4 | 31.2 ± 9 | 31.5 ± 8 | 26.2 ± 8.2 | 29.2 ± 8.2 | 25.8 ± 12.2 |

| P-value | 0.023 | 0.08 | |||||

| ASDS | 60.6 ± 12.9 | 64.9 ± 10.8 | 61 ± 12.9 | 62.5 ± 12.6 | 60.9 ± 12.5 | 67.5 ± 7 | 63.4 ± 14.4 |

| P-value | 0.058 | 0.511 | |||||

Table 2: Distribution of fear, GAD, depressive symptoms, PSQI, psychological discomfort and ASDS, as well as their differences in relation to resident’s demographic variables.

The results of the associations of scales of fear, GAD, depressive symptoms, PSQI, psychological discomfort and ASDS with residents’ demographic variables during the coronavirus pandemic are shown in Table 3 and Figure 1.

| Variable | Age | Academic year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 (n=74) | ≥ 30 (n=51) | First year (n=35) | Second year (n=42) | Third year (n=27) | Fourth year (n=14) | Fifth year (n=7) | |

| Fear (P-value) | 0.513 | 0.89 | 0.48 | 0.87 | 0.47 | 0.621 | |

| OR (95% Cl) | 2.11 (0.214-20.90) | 0.117 (0.11-11.66) | 0.49 (0.06-3.63) | 0.82 (0.08-8.22) | 1.13 (1.06-1.2) | 1.06 (1.01-1.1) | |

| GAD (P-value) | 0.645 | 0.115 | 0.018 | 0.252 | 0.607 | 0.338 | |

| OR (95% Cl) | 1.20 (0.54-2.67) | 0.45 (0.17-1.22) | 2.64 (1.16-5.96) | 0.54 (0.18-1.56) | 0.7 (0.18-2.69) | 2.1 (0.44-9.93) | |

| Depressive symptoms (P-value) | 0.263 | 0.555 | 0.656 | 0.911 | 0.138 | 0.813 | |

| OR (95% Cl) | 0.66 (0.32-1.36) | 1.26 (0.57-2.76) | 1.18 (0.56-2.49) | 1.05 (0.44-2.46) | 0.4 (0.12-1.37) | 0.83 (0.17-3.87) | |

| PSQI (P-value) | 0.79 | 0.026 | 0.858 | 0.042 | 0.759 | 0.526 | |

| OR (95% Cl) | 0.90 (0.42-1.93) | 2.93 (1.10-7.79) | 1.07 (0.48-2.39) | 0.41 (0.17-0.98) | 0.82 (0.25-2.65) | 0.609 (0.130-2.86) | |

| Psychological discomfort (P-value) | 0.63 | 0.766 | 0.362 | 0.763 | 0.663 | 0.227 | |

| OR (95% Cl) | 0.67 (0.31-3.49) | 0.76 (0.13-4.39) | 2.62 (0.29-23.25) | 1.39 (0.15-12.49) | 0.61 (0.06-5.66) | 0.26 (0.02-2.64) | |

| ASDS (P-value) | 0.009 | 0.135 | 0.928 | 0.947 | 0.03 | 0.806 | |

| OR (95% Cl) | 2.95 (1.28-6.78) | 0.54 (0.24-1.21) | 0.96 (0.43-2.21) | 0.97 (0.39-2.39) | 7.32 (0.92-0.58) | 1.23 (0.22-6.64) | |

Table 3: Associations of scales of fear, GAD, depressive symptoms, PSQI, psychological discomfort and ASDS with residents’ demographic variables during the Coronavirus pandemic.

• First year residents, were more likely to rate their sleep

disturbances as severe compared to other residents

(P=0.026, or=2.93 (1.10-7.79)).

• Second year residents, were more likely to rate their GAD

as severe compared to other residents (P=0.018, or=2.64

(1.16-5.96)).

• Third year residents, were more likely to rate their sleep

disturbances as mild compared to other residents

(P=0.042, or=0.41 (0.17-0.98)).

• Fourth year residents, were more likely to rate their

ASDS as severe compared to other residents (P=0.03,

or=7.32 (0.92-0.58)).

• Upper the age of 30 residents, were more likely to rate

their ASDS as severe compared to other residents

(P=0.009, or=2.95 (1.28-6.78)).

Discussion

The major objective of this study is to investigate the influence of a pandemic, here the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, on the psychological consequences of the neurosurgery residents’. As no previous epidemic or pandemic in the last decades hit all countries that hard, especially Iran, the influence of such a pandemic on the psychological consequences of the neurosurgery residents’ remains unclear. The identification of psychological consequences will help to facilitate the understanding of pandemic outcomes, and how to deal with them consequences on an academic level.

The results of the analysis show a prevalence of symptoms such as psychological discomfort, acute stress disorder, sleep disturbances, and fear across the neurosurgery residents. 85 (68%) of the participants reported to suffer from high levels of psychological discomfort and 84 (67.2%) reported to suffer from high levels of acute stress disorder. 34 (27.2%) of the neurosurgery residents reported low levels, GAD symptoms. 121 (96.8%) of the participants reported, to suffer from moderate to high levels of fear. It looks similar for sleep disturbances with 119 (95.2%) of the participants indicated moderate to high levels.

The findings mentioned above underline consistent with research findings from other countries. Husky et al., investigated stress and anxiety among university students in France during COVID-19 mandatory confinement also showing increased levels of anxiety and stress. Another study, conducted by Shevlin et al. in the UK, shows moderate to high levels of anxiety (GAD) associated with COVID-19.

Similar results were obtained by a study conducted in Italy by Gualano et al. Italy was the first country in Europe that entered a nationwide lockdown with very high cases and deaths associated with COVID-19. This study shows a general prevalence of anxiety (23.2%) and depression symptoms (24.7%) as well as sleep disturbances (42.2%).

Huang and Zhao identified higher levels of GAD, depressive symptoms and sleep quality across the general Chinese public. Furthermore, the meta-analyses conducted by Ng et al., on the effects of COVID-19 on the mental constitution of healthcare workers in Asia show increased symptom prevalence, especially anxiety and depressive symptoms. The study of Li et al., “aimed to investigate the COVID-19 related factors that were associated with sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts among members of the public during the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan”. Their results underline that a higher prevalence of sleep disturbances and suicidal thoughts are associated with the virus outbreak compared to results from a previous population-based survey undertaken before the outbreak.

In the current pandemic, a recent study in this line carried out in China, revealed that 54% of respondents showed moderate to severe persistent psychological impact, 16% and 29% moderate to high depressive or anxiety symptoms, respectively, and 8% moderate to high levels of stress. Besides, anxiety and depression symptoms showed no decline four weeks after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our study showed that all residents reported medium depressive symptoms reactions. Similar results were obtained in an extensive study conducted in nine countries by Ochnik et al., which showed that students worldwide did not differ much in their reactions to the pandemic, but also that students in their younger years were more likely to self-report more depressive.

The results underline that older people (upper 30) seem to be more affected with the occurrence of psychological consequences issues, such as acute stress disorder, than younger people.

This goes in no line with the results of the European health interview survey, conducted before the pandemic crisis [20].

Jia in a systematic review, it was stated that the prevalence of depression and anxiety among medical students varied by gender, country, and continent.

Perissotto stated that we found high levels of mental burden in medical students in the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in first year students, who may have fewer resources to deal with stress. Moreover, as they entered college a short time before the pandemic, they were unable to experience academic life fully or create important new social support networks to deal with adversities.

In Isfahan, the residents cannot get specialist consultative services (covered by health insurance) for the protection of their mental health at the Institute for students’ healthcare as primary health care institution. There is no program or center for psychological counseling at Isfahan medical university so the creation of a network of centers for counseling and psychological help for students as an integrated part of the health system is of crucial importance for the prevention and protection of mental health.

Conclusion

The present study identified certain psychological issues associated with the crisis and reinforces previous findings. The COVID-19 pandemic had a great impact on the overall psychological consequences of residents and therefore it is important to pay attention to preserving their mental health and to launch programs that would provide primarily social support and assistance in the form of consultative work. Also psychological health issues produce consequential costs.

References

- Ihm L, Zhang H, Vijfeijken A. Waugh M. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of university students. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36:618–627.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baloch S, Baloch M. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2020;250:271-278.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hamid S, Yaseen H. Novel Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): A pandemic (epidemiology, pathogenesis and potential therapeutics). New Microbes New Infect. 2020; 35:100679.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, Nordentoft M, Crossley N, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7:813–824.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Li X, He T. Impact of physical activity on COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14108.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Fernandez L, Romero-Ferreiro V, Padilla S, David Lopez-Roldan P, Monzo-Garcia M, et al. Gender differences in emotional response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Brain Behav. 2021;11:01934.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linda CK, Soveri A. The behavioral immune system and vaccination intentions during the coronavirus pandemic. Pers Individ Dif. 2022;185:111295.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alison MB, Philip JC. Behavioral immune system responses to Coronavirus: A reinforcement sensitivity theory explanation of conformity, warmth toward others and attitudes toward lockdown. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566237.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shook Natalie J, Sevi B. Disease avoidance in the time of COVID-19: The behavioral immune system is associated with concern and preventative health behaviors. PLoS One. 2020;15:0238015.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Makhanovaa A, Melissa AS. Behavioral immune system linked to responses to the threat of COVID-19. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;167:110221.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Francisco R, Pedro M, Delvecchio E. Psychological symptoms and behavioral changes in children and adolescents during the early phase of COVID-19 quarantine in three European countries. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:570164.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Tang J, Shen C. Research of the changes in the psychological status of Chinese university students and the influencing factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2022;13:891778.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koole Sander L, Rothermund K. Coping with COVID-19: Insights from cognition and emotion research. Cogn Emot. 2022;36:1-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gardikiotis A, Malinaki E. Castellano-Tejedor C, Torres-Serrano M. Psychological impact in the time of COVID-19: A cross-sectional population survey study during confinement. J Health Psychol. 2022;27:974–989.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gardikiotis A, Malinaki E, Charisiadis-Tsitlakidis C, Protonotariou A, Archontis S, et al. Emotional and cognitive responses to COVID-19 information overload under lockdown predict media attention and risk perceptions of COVID-19. J Health Commun. 2021;26:434-442.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tsamakis K, Tsiptsios D, Ouranidis A. COVID-19 and its consequences on mental health (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;21:244.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pistarini C, Fiabane E, Houdaye E. Cognitive and emotional disturbances due to COVID-19: An Exploratory study in the rehabilitation setting. Front Neurol. 2021;12:643646.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dhira TA, Mahir AR. Validity and reliability of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among university students of Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2021;16:0261590.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang L, Wang Y, Zhang Y. The reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) for Chinese university students. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:315.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang C, Zhang H, Zhao M. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of Pittsburgh sleep quality index in community based centenarians. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:573530.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.