Timing of first antenatal care attendance and associated factors among pregnant women at public Health Facilities of Hawassa City, Sidama, Ethiopia

2 Department of Public Health, Hawassa College of Health Sciences, Hawassa, Ethiopia

3 Department of Nursing, Hawassa College of Health Sciences, Hawassa, Ethiopia

, Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-121929; , Pre QC No. AMHSR-23-121929; QC No. AMHSR-23-121929; , Manuscript No. AMHSR-23-121929; Published: 24-Jan-2025

This open-access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (CC BY-NC) (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits reuse, distribution and reproduction of the article, provided that the original work is properly cited and the reuse is restricted to noncommercial purposes. For commercial reuse, contact reprints@pulsus.com

Abstract

Background: Timely initiation of antenatal care can reduce pregnancy related problems and save the lives of mothers and babies. The African region has large intraregional disparities in terms of coverage of basic maternal health interventions like antenatal care. This study was aimed at assessing the timing of first antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women who attend antenatal care clinics at public health centers in Hawassa city. Methods: An institution-based cross-sectional study was carried out in Hawassa city public health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022. A total of 235 randomly selected mothers who attend at ANC clinic were included in the study. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect the data. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the data. A logistic regression model was used to analyze the data using statistical package for social sciences version 26. An adjusted odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval and a corresponding p-value <0.05 was used to determine factors associated with the outcome variable. Result: Among the respondents, 173 (73.6%) initiated their first antennal care after 16 weeks of gestation, and 62 (26.4%) initiated it before 16 weeks of gestation. Having no information about ANC service (AOR=0.06, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.58, (late previous first antenatal care attendance (AOR=0.037, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.11), and unplanned pregnancy (AOR=0.07, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.39) were significantly associated with late antenatal care. Conclusion: The prevalence of late first antenatal care was high in the study area. We have identified different factors affecting the late antenatal care visit. Interventions should focus on reducing those risk factors.

Keywords

Associated factors; Antenatal care; Late ANC initiation; Hawassa

Introduction

Antenatal Care (ANC) is defined as the care provided by skilled health care professionals to pregnant women and adolescent girls in order to ensure the best health conditions for both mother and baby during pregnancy [1]. The components of ANC are risk identification, prevention and management of pregnancy-related or concurrent diseases, health education, and health promotion. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that pregnant women in developing countries initiate early prenatal care before the end of the fourth month of pregnancy. ANC in the first trimester is fundamental and decisive in identifying and evaluating the risk factors usually present before pregnancy [2]. However, in developing countries, the coverage and early initiation of ANC are lower than in developed countries. A significant number of pregnant women started their first ANC visit during the second and third trimesters because of different factors in different developing countries [3].

Worldwide, 85 percent of pregnant women received antenatal care with skilled health care providers at least once, and only 49 percent received at least four antenatal visits in sub- Saharan Africa [4]. Globally, more than half a million women are still dying annually as a result of complications of pregnancy and childbirth, and ninety-nine percent of these occur in developing countries [5]. Of these deaths, 50 percent occurred in sub-Saharan Africa [6]. According to the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey Report (EDHS), 62 percent of women who gave birth in the five years preceding the survey received antenatal care from a skilled health care provider at least once for their last birth, and only 32 percent had four or more ANC visits for their most recent live birth [7]. The lifetime death risk of a woman from pregnancy-related causes in sub-Saharan Africa is 1 in 16, which is 500 times higher than for a woman in northern Europe [8].

Age, a woman’s place of residence, level of education, employment status, intention to get pregnant, economic status, health insurance, parity, and traveling time are among the most cited factors related to late ANC visits.

Proper care during pregnancy and delivery is important for the health of both the mother and the baby. Antenatal care from a skilled provider is important to monitor pregnancy and reduce morbidity and mortality risks for the mother and child during pregnancy, delivery, and the postnatal period. In developing countries, however, only 50 percent of pregnant mothers receive the recommended number of antenatal care visits and start late in their pregnancy. To our knowledge, there are limited studies conducted on ANC and its associated factors in the study area. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the magnitude and factors associated with the timing of antenatal care attendance in Hawassa city, Sidama, Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

Study setting and design

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Hawassa city, the capital of the Sidama region, which is located 275 kilometers south of Addis Ababa. The total population of the city is 394,057. There are 4 public hospitals (Hawassa University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Adare General Hospital, Motite Primary Hospital, and Tula Primary Hospitals), 4 non-governmental hospitals, 11 governmental and 1 non-government health centers, and 7 diagnostic laboratories in the city [9]. Of these, three randomly selected health centers were included in the study.

Study population and sample size

Mothers who were following ANC at the health centers of Hawassa city administration were included in the study. Women who were mentally and physically incapable of being interviewed, including those who were ill, were excluded from the study. Three health centers (Tula, Alamura, and Millennium) were randomly selected among the eleven health centers found in the city. A systematic random sampling technique was used to select study participants. A single population proportion formula was used to calculate the sample size. Using the assumptions, the level of significance is 5%, the margin of error is 5%, and the prevalence of late initiation of ANC is 82.6% [10]. A contingency of 10% was considered for non-respondents. Finally, a total of 235 pregnant mothers participated in the study.

Data collection tools and procedures

The questionnaire was developed after reviewing literature that has similar study objectives and the EDHS tools. The questionnaire was developed in English first and then translated into Amharic by a translator to ensure its consistency. Finally, it was translated back into English. A structured questionnaire, which contains questions on the socio-demographic characteristics of the mothers, their knowledge of ANC, their past history of ANC service utilization, their current pregnancy, their current utilization of antenatal care, and the timing of their first ANC-related measures, was used to collect the data. The timing of the ANC visit was explained as a categorical variable with two possible values: Early beginning of the ANC ("yes") or late initiation ("no") of the ANC visit. Information regarding the study was explained to study participants before the interview. Data was collected from mothers through direct interviews conducted in Amharic face-to-face at the exit of the ANC clinic. Data collection was conducted by four trained BSc midwives on day and night rotations to address the assigned sample size. To minimize bias and ensure the high quality of the information, training was given to data collectors and supervisors. Before data collection, 5% of the sample was pretested, and corrections were made outside of the study area. Throughout the data collection process, monitoring of the data collection, timely feedback, and checking for questionnaire completeness and consistency were done.

Statistical analysis

The data cleaning and analyses was done using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 26. Descriptive statistics was used to summarize the data. Logistic regression model was used to analyze the data. Bivariable analysis was conducted to identify candidate variables for the final model, considering p-value <0.25. An Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval was used to determine factors associated with the outcome variable with a p-value <0.05, to declare statistical significance.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

A total of 235 study subjects participated in this study, with a response rate of 100%. The mean age of the respondents was 27 years, ranging from 15 to 39 years. The majority, 89 (37.9%), were in the age group of 25–29 years. Regarding ethnicity, about 105 (44.7%) were Sidama, followed by Wolyta (57, 24.7%). More than half, 133 (56.6%), were Protestant, 76 (32.3%) were Orthodox, 19 (8.1%) Muslims, 3 (1.3%) Catholic, and 4 (1.7%) others. Among 235 respondents, 232 (98.7%) were married, 2 (0.9%) unmarried, and the rest (1.4%) widowed. More than half of the respondents' educational level was secondary school (9–12 grade) and college/university, accounting for 87 (37.0%) and 75 (31.9%), respectively. The net income of 185 (78.7%) respondents was greater than 2000 ETB, while only 12 (5.1%) earned between 500–1000 ETB per month (Table 1).

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the mother | 15-19 | 9 | 3.8 |

| 20-24 | 74 | 31.5 | |

| 25-29 | 89 | 37.9 | |

| 30-34 | 46 | 19.6 | |

| ≥ 35 | 17 | 7.2 | |

| Ethnicity | Sidama | 105 | 44.7 |

| Wolyta | 57 | 24.3 | |

| Oromo | GD16 | 6.8 | |

| Amhara | 29 | 12.3 | |

| Gurage | 20 | 8.5 | |

| Other | 8 | 3.4 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 76 | 32.3 |

| Protestant | 133 | 56.6 | |

| Muslim | 19 | 8.1 | |

| Catholic | 3 | 1.3 | |

| Other | 4 | 1.7 | |

| Marital status | Married | 232 | 98.7 |

| Unmarried | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.4 | |

| Education of women | Illiterate | 8 | 3.4 |

| Primary school (1-8 grade) | 65 | 27.7 | |

| Secondary school (9-12 grade) | 87 | 37 | |

| College/university | 75 | 31.9 | |

| Occupation of women | Governmental employee | 66 | 28.1 |

| Private employee | 7 | 3 | |

| Private business | 40 | 17 | |

| House wife | 98 | 41.7 | |

| Student | 24 | 10.2 | |

| Educational of husband | Primary school (1-8 grade) | 17 | 7.2 |

| Secondary school (9-12 grade) | 46 | 19.6 | |

| College/University | 172 | 73.2 | |

| Occupation of husband | Governmental employee | 167 | 71.1 |

| Private employee | 16 | 6.8 | |

| Private business | 49 | 20.9 | |

| Daily laborer | 3 | 1.3 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022, n=235.

Economic and pregnancy-related factors of pregnant women attending first ANC visit

More than three-fourths (185, 78.7%) had monthly incomes >2000 ETB, while only 12 (5.1%) earned 500–1000 ETB. About 173 (75.9%) paid nothing for transportation and 154 (65.54%) paid <20 ETB. Regarding number of pregnancies, 98 (41.7%) had one, while 32 (13.6%) had four or more. About 204 (86.8%) had no history of abortion. Regarding parity, 106 (45.1%) had none, and 8 (3.4%) had four or more. Most (23, 98.3%) had a history of stillbirth (Table 2).

| Variables (n=235) | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net income per month | 500-1000 ETB | 12 | 5.1 |

| 1001-2000 ETB | 38 | 16.2 | |

| >2000 ETB | 185 | 78.7 | |

| Payment for transportation | Yes | 55 | 24.1 |

| No | 173 | 75.9 | |

| Amount of money paid for transportation | <20 ETB | 154 | 65.54 |

| >20 ETB | 81 | 34.46 | |

| Number of pregnancy | Once | 98 | 41.7 |

| Twice | 62 | 26.4 | |

| For three times | 43 | 18.3 | |

| For 4 and more times | 32 | 13.6 | |

| History of abortion | Yes | 31 | 13.2 |

| No | 204 | 86.8 | |

| Number of parity | Once | 67 | 28.5 |

| Twice | 35 | 14.9 | |

| For three times | 19 | 8.1 | |

| For 4 and more times | 8 | 3.4 | |

| None | 106 | 45.1 | |

| History of still birth | Yes | 4 | 1.7 |

| No | 231 | 98.3 |

Table 2: Economic and pregnancy related factors of pregnant women who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022.

The knowledge status of pregnant women towards ANC services

All respondents (100%) agreed that ANC is important. About 4 (1.7%) thought it should start in the first month, 28 (11.9%) in the second month, 105 (44.7%) in the third month, 91 (38.7%) in the fourth month, and 7.0% in the fifth month or later. Regarding frequency of ANC, 3 (1.3%) thought it was two times, 30 (12.8%) three times, 136 (57.9%) four times, and 66 (28.1%) five or more. About 121 (51.5%) had no knowledge of danger signs, while 114 (48.5%) were aware, mainly of vaginal bleeding and cessation of fetal movement (Table 3).

| Variable (n=235) | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of ANC service for the mother | Yes | 235 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | |

| The time perceived by the mother to initiate first ANC booking after amenorrhea | First month | 4 | 1.7 |

| Second month | 28 | 11.9 | |

| Third month | 105 | 44.7 | |

| Four | 91 | 38.7 | |

| Five and above month | 7 | 3 | |

| The time perceived by the mother for the women needs to go for ANC during pregnancy | Two times | 3 | 1.3 |

| Three times | 30 | 12.8 | |

| Four times | 136 | 57.9 | |

| 5 or more times | 66 | 28.1 | |

| Knowledge on danger sign | Yes | 137 | 58.3 |

| No | 98 | 41.7 | |

| Mentioned danger signs by the mother | Vaginal bleeding | 47 | 34.3 |

| Cessation of fetal movement | 42 | 30.7 | |

| Persistent headache | 26 | 19 | |

| Face and leg edema | 17 | 12.4 | |

| Blurred vision | 5 | 3.6 |

Table 3: The knowledge status of the pregnant women towards the ANC service who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022.

Past history of ANC service utilization among pregnant women

During the previous pregnancy, 8 (5.8%) had not utilized ANC services, while 129 (94.2%) did. Among those, 53 (41.1%) initiated their first ANC visit within 16 weeks, while 75 (58.9%) started after 16 weeks. Although services were free, some respondents paid for ultrasounds (100–200 ETB) (Table 4).

| Variables (n=235) | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous ANC utilization | Yes | 129 | 94.2 |

| No | 8 | 5.8 | |

| The time the mother start her first ANC visit | ≤ 16 weeks | 53 | 41.1 |

| >16 weeks | 76 | 58.9 | |

| Payment during previous pregnancy | Yes | 3 | 2.3 |

| No | 126 | 97.7 | |

| The service paid during check up | Card | 0 | 0 |

| Laboratory | 0 | 0 | |

| Ultrasound | 3 | 100 | |

| Drugs | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum birr asked for the service | <100 ETB | 0 | 0 |

| 100-200 ETB | 3 | 100 | |

| >200 ETB | 0 | 0 |

Table 4: Past history of ANC service utilization of pregnant women who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022.

History of current pregnancy

About 131 (55.7%) realized pregnancy through missed periods, 81 (34.5%) through lab tests, 21 (8.9%) through physiological/physical changes, and the rest (2.9%) via ultrasound. 62 (26.4%) initiated ANC within 16 weeks, while 173 (73.6%) did so after. Of the respondents, 137 (58.3%) had information about ANC, and 98 (41.7%) did not. Family planning use before pregnancy was reported by 188 (80.0%), with injectables (53.2%) and implants (35.1%) being most common. Planned pregnancies were reported by 202 (85.5%) respondents (Table 5).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Means to know pregnancy | Missed period | 131 | 55.7 |

| Laboratory | 81 | 34.5 | |

| Physiological change | 21 | 8.9 | |

| Ultrasound | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Gestational age of this pregnancy | Less or equal to 16 weeks | 62 | 26.4 |

| >16 weeks | 173 | 73.6 | |

| Information about ANC service | Yes | 137 | 58.3 |

| No | 98 | 41,7 | |

| History of family use | Yes | 188 | 80 |

| No | 47 | 20 | |

| Type of family planning used | Condom | 2 | 1.1 |

| Pills | 12 | 6.4 | |

| Inject able | 100 | 53.2 | |

| Implant | 66 | 35.1 | |

| IUCD | 3 | 1.6 | |

| Natural | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Planned pregnancy | Yes | 202 | 86 |

| No | 33 | 14 | |

| Involvement of husband on pregnancy planning | Yes | 202 | 100 |

| No | 0 | 0 | |

| Acceptance of unplanned pregnancy by the husband | Yes | 29 | 87.9 |

| No | 4 | 12.1 |

Table 5: Current pregnancy history of pregnant women who attend ANC clinic for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022.

Current ANC service utilization of pregnant women

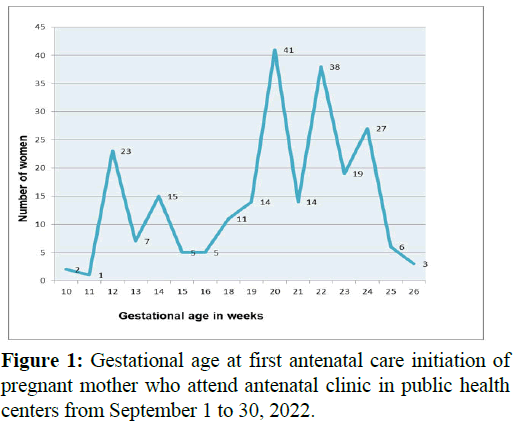

Among participants, 198 (84.3%) came for a pregnancy checkup, and 37 (15.7%) for TT vaccination. Most (218, 92.8%) visited the clinic themselves. More than two-thirds (68.9%) initiated their first ANC after 16 weeks, mainly due to advice from health professionals (51.5%), absence of problems (18.4%), acceptance of timing (25.2%), or workload (11.8%) (Table 6, Figure 1).

| Table 6: Current ANC service utilization of pregnant women who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers September 1 to 30, 2022. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| The reason given by the women to come to ANC clinic during this pregnancy | Check up | 198 | 84.3 |

| To take TT vaccine only | 37 | 15.7 | |

| Decision making power of the women | Yes | 218 | 92.8 |

| No | 17 | 7.2 | |

| The reason given by the mother for late initiation of ANC in current pregnancy | Health professionals advice not to come early before 4 month | 119 | 50.6 |

| No health problem | 45 | 19.15 | |

| Right time to start | 39 | 16.59 | |

| Work load | 32 | 13.66 | |

| Plan for delivery | At health institution | 216 | 91.9 |

| At home | 4 | 1.7 | |

| I did not decide | 15 | 6.4 | |

Table 6: Current ANC service utilization of pregnant women who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers September 1 to 30, 2022.

Factors associated with late initiation of the first ANC visit

Bivariate logistic regression identified variables with p-value <0.25 for multivariable analysis. Previous late first ANC initiation, lack of information about ANC services, and unplanned pregnancy were significant factors (Table 7).

| Variables | Time of first ANC initiation, n=235 | Crude OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 16 weeks of gestation | >16 weeks of gestation | |||

| Age of the women | ||||

| 15-19 | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0.14 (0.02,1.38) | 0.093 |

| 20-24 | 21 (28.4%) | 53 (71.6%) | 0.45 (0.15,1.31) | 0.446 |

| 25-29 | 18 (20.2%) | 71 (79.8%) | 0.26 (0.96,0.84) | 0.285 |

| 30-34 | 14 (30.4%) | 32 (69.6%) | 0.60 (0.19,1.86) | 0.6 |

| 35-39 | 8 (47.1%) | 9 (52.9%) | 1 | |

| Educational level | ||||

| Illiterate | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0.32 (0.04,2.78) | 0.303 |

| Primary (1-8) | 17 (26.2%) | 48 (73.8%) | 0.81 (0.38,1.68) | 0.556 |

| Secondary (9-12) | 23 (26.4%) | 64 (73.6%) | 0.82 (0.41,1.61) | 0.552 |

| College/University | 21 (28.0%) | 54 (72.0%) | 1 | |

| Monthly income | ||||

| <500 ETB | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 500-999 ETB | 1 (8.3%) | 11 (91.7%) | 0.23 (0.03,1.79) | 0.16 |

| 1000-2000 ETB | 10 (26.3%) | 28 (73.7%) | 0.89 (0.41,1.96) | 0.771 |

| >2000 ETB | 51 (27.6%) | 134 (72.4%) | 1 | |

| History of abortion | ||||

| Yes | 9 (29.0%) | 22 (71.0%) | 1 | |

| No | 53 (26.0%) | 151 (74.0%) | 1.11 (0.48,2.55) | 0.809 |

| History of still birth | ||||

| Yes | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 1 | |

| No | 61 (26.4%) | 170 (73.6%) | 0.89 (0.09,8.71) | 0.919 |

| Number of birth | ||||

| Once | 16 (23.9%) | 51 (76.1%) | 1.02 (0.49,2.09) | 0.964 |

| Twice | 13 (37.1%) | 22 (62.9%) | 1.92 (0.84,4.34) | 0.12 |

| Three times | 5 (26.3%) | 14 (73.7%) | 1.89 (0.67,5.32) | 0.228 |

| Four and above | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 1.93 (0.43,8.73) | 0.385 |

| None | 25 (23.6%) | 81 (76.4%) | 1 | |

| Information about ANC service | ||||

| Yes | 55 (40.1%) | 82 (59.9%) | 1 | |

| No | 7 (7.1%) | 91 (92.9%) | 9.26 (3.99, 21.47) | 0.000* |

| Previous time of first ANC initiation | ||||

| ≤ 16 weeks | 32 (60.4%) | 21 (39.6%) | 1 | |

| >16 weeks | 5 (6.6%) | 71 (93.4%) | 15.02 (5.79,38.94) | 0.000* |

| Pregnancy planned | ||||

| Yes | 61 (30.2%) | 141 (69.8%) | 1 | |

| No | 1 (3.0%) | 32 (97.0%) | 4.33 (1.27,14.72) | 0.019** |

| Decision by the mother to start ANC | ||||

| Yes | 61 (28.0%) | 157 (72.0%) | 1 | |

| No | 1 (5.9%) | 16 (94.1%) | 1.82 (0.51,6.53) | 0.363 |

Table 7: Bi-variable analysis of factors associated with late initiation of first antenatal care among pregnant women who attend ANC clinic late for the first ANC visit in public health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022.

Interpretation of the multivariable analysis result

In the current study, pregnant mothers who have no information about ANC visits were 9 times more likely to initiate ANC after the recommended time of first ANC compared to pregnant mothers who have information (AOR=0.06; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.58). Mothers who initiate their first ANC after 16 weeks of gestation in a previous pregnancy were 15 times more likely to initiate their first ANC in this pregnancy than mothers who initiate early in the previous pregnancy (AOR=0.04; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.11). Mothers whose pregnancy was unplanned were 4 times more likely to initiate first antenatal care late as compared to mothers whose pregnancy was planned (AOR=0.07; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.39) (Table 8).

| Characteristics | Time of first ANC initiation, n=235 | Crude OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <16 weeks of gestation | >16 weeks of gestation | |||

| Information about ANC service | ||||

| Yes | 55 (40.1%) | 82 (59.9%) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| No | 7 (7.1%) | 91 (92.9%) | 9.26 (3.99, 21.47) | 0.06 (0.01,0.58)* |

| Previous time of first ANC initiation | ||||

| <16 weeks | 32 (60.4%) | 21 (39.6%) | 1.00 | |

| >16 weeks | 5 (6.6%) | 71 (93.4%) | 15.02(5.79, 38.94) | 0.04 (0.02, 0.12)* |

| Pregnancy plan | ||||

| Yes | 61 (30.2%) | 141 (69.8%) | 1.00 | |

| No | 1 (3.0%) | 32 (97.0%) | 4.33 (1.27, 14.72) | 0.07 (0.02, 0.39)** |

Table 8: Factors associated with late initiation of ANC among pregnant women who come for the first ANC visit in three selected health centers from September 1 to 30, 2022.

Discussion

Our study was conducted in health centers, considering it is the first place where the majority of pregnant women prefer to get maternal health services compared to hospitals and other private clinics. In our study, 235 pregnant women participated. The majority 173 (73.6%) of the participants initiate their first antenatal care after 16 weeks of gestation, while 62 (26.4%) of respondents initiate it before and at 16 weeks of gestation. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends every pregnant woman start the first antenatal care visit before or at 16 weeks of gestation. Our study indicates that a considerable proportion of pregnant women initiate their first antenatal care visit after 16 weeks of gestation. The result of this study is greater than the results of studies done in Mekele (67.3%), Halaba (72.8%), and Dilla, Ethiopia (50.3%) and Tanzania (71%), respectively. However, our study result is less than the results of studies conducted in Wollega (81.5%), Ambo (86.8%), and Arbaminch, Ethiopia (82.6%), respectively [11-15]. This difference may be due to the differences in sociodemographic characteristics and economic and cultural factors among respondents. Mothers who are illiterate, have a monthly net income of less than 500-1000 Ethiopian birr, gave birth twice or more, and have no history of stillbirth or abortion are more likely to initiate their first antenatal care after the recommended period of gestation. The reasons given by the mother for their late first antenatal care initiation are health professionals' advice not to come early before 4 months to initiate first antenatal care, no health problems, the right time to start first antenatal care, and work load in the office (work place). Additionally, the majority of women who attended antenatal care clinics during their previous pregnancy did not have knowledge of danger signs, the timing of their first antenatal care, or the recommended frequency of antenatal care visits. This indicates the negligence of health providers towards antenatal care service delivery. This is the first area to focus on to prevent these problems.

In this study, women’s status of information about antenatal care services was significantly associated with timely initiation of antenatal care. Women who have no information about antenatal care services were more likely to initiate their first antenatal care visit late than those who had information. Our finding is similar to the results of study conducted in Halaba, Ethiopia [16]. The possible justification could be that a lack of information delivery for mothers who have come for antenatal care previously and the absence of information about antenatal care in different media.

This study revealed that there was a statistically significant association between previous late first antenatal care initiation and the timely initiation of first antenatal care. Women who initiated first antenatal care late during a previous pregnancy were 15 times more likely to initiate late in this pregnancy than women who initiated early during a previous pregnancy. A similar finding was identified in studies done in Ethiopia [17], 18]. The possible reason might be due to the advice of health professionals for pregnant women not to come early to the antenatal care clinic to initiate first antenatal care before 4 months of pregnancy, a lack of information about the timing and visits of antenatal care, the negligence of the mother towards the service, and a lack of awareness of danger signs.

In the current study, unplanned pregnancy was significantly associated with the timely initiation of antenatal care services. Women with unplanned pregnancies were more likely to initiate antenatal care after the recommended time of pregnancy. This finding is supported by studies done in Ethiopia [19], 20]. This is might be due to a lack of knowledge about the pregnancy plan and a reluctance to seek proper care for the health and development of the pregnancy.

Conclusion

This study assessed the timing of first antenatal care and the associated factors among pregnant women who come to antenatal clinics in public health centers. The study has reported a high prevalence of late-first antenatal care. In our study, 73.6% of respondents initiated first antenatal care after the recommended time, while the rest, 26.4%, initiated first antenatal care within the recommended time. The major identified factors that contributed to the late initiation of first antenatal care were lack of information about antenatal care, previous late initiation of first antenatal care, and unplanned pregnancy. The main reasons raised by the mother for the late initiation of first antenatal care were health professional`s advice not to come early before 4 month to the clinic for the first antenatal care, no health problems, and work load in the office (work area). Accordingly, it is important to provide continuous health education on importance of early antenatal care visits at health facility.

Limitation of the Study

For those mothers who did not remember their last normal menstrual period, it was challenging to estimate the gestational age of the pregnancy. Our study was conducted in health centers; private clinics and hospitals were not included in our study, so the results could not be generalized to general populations. Furthermore, it was difficult to establish causeeffect relationship between variable since it was a crosssectional study.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from research review and ethics committee of Hawassa College of Health Sciences. Legal permission was obtained from the health centers. The respondents were informed about the purpose of the study and their right to withdraw at any time. Furthermore, written consent was obtained from each respondent. Informed assent was obtained from a parent or guardian for study participants younger than 18 years of age. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the study by excluding personal identifiers, such as names and addresses.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution

SK, ST, AA, BH, AF, and TB conceived, designed the study, contributed to data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors equally contributed and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The original datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all study participants for their cooperation, as well as data collectors and supervisors for their dedication during the data collection process.

References

- Mohamed SA, Fahmy NM, Mohamed SM, Morshedy NA. Effect of Self-Care Guideline on Quality of Life among Pregnant Women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Evid Based Nurs Res. 2019;1:15.

- Jolivet RR, Gausman J, Kapoor N, Langer A, Sharma J, et al. Operationalizing respectful maternity care at the healthcare provider level: A systematic scoping review. Reprod Health. 2021;18:1-15.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manzi A, Munyaneza F, Mujawase F, Banamwana L, Sayinzoga F, et al. Assessing predictors of delayed antenatal care visits in Rwanda: A secondary analysis of Rwanda demographic and health survey 2010. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:290.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tikmani SS, Ali SA, Saleem S, Bann CM, Mwenechanya M, et al. Trends of antenatal care during pregnancy in low-and middle-income countries: Findings from the global network maternal and newborn health registry. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:297-307.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990-2015: Estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and The United Nations Population Division. World Health Organization. 2015.

- Hogan MC, Foreman KJ, Naghavi M, Ahn SY, Wang M, et al. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980-2008: A systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 2010;375:1609-1623. [Crossref]

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wolde HF, Gonete KA, Akalu TY, Baraki AG, Lakew AM. Factors affecting neonatal mortality in the general population: Evidence from the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS)-multilevel analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:610.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gerezigiher T. Predictors of timing of first antenatal care booking at public health centers in Mekelle city, Northern Ethiopia. J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;3:55-60.

- Ababa A. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia central statistical agency population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Wereda level from 2014-2017. Addis Ababa: Central Statistical Agency. 2018.

- Gross K, Alba S, Glass TR, Schellenberg JA, Obrist B. Timing of antenatal care for adolescent and adult pregnant women in south-eastern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:16.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asefa A, Beyene H. Awareness and knowledge on timing of mother-to-child transmission of HIV among antenatal care attending women in Southern Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Reprod Health. 2013;10:66.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banda I, Michelo C, Hazemba A. Factors associated with late antenatal care attendance in selected rural and urban communities of the copperbelt province of Zambia. Med J Zambia. 2012;39:29-36.

- Battu GG, Kassa RT, Negeri HA, Kitawu LD, Alemu KD. Late antenatal care booking and associated factors among pregnant women in Mizan-Aman town, South West Ethiopia, 2021. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3:e0000311.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kondale M, Tumebo T, Gultie T, Megersa T, Yirga H. Timing of first antenatal care visit and associated factors among pregnant women attending anatal clinics in Halaba Kulito governmental health institutions, 2015. J Women's Health Care. 2016;5:1000308.

- Tekelab T, Berhanu B. Factors associated with late initiation of antenatal care among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at public health centers in Kembata Tembaro zone, southern Ethiopia. Sci Technol Arts Res J. 2014;3:108-115.

- Gopakumar A. Pattern and Determinants of Antenatal Booking at Abakaliki Southeast Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3:132-134.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olana R, Lamaro T, Henok A. Assessment of antenatal care utilization among reproductive age group women of Mizan-Aman town, Southwest Ethiopia. Primary Health Care. 2016;6:1000217.

- Girma N, Abdo M, Kalu S, Alemayehu A, Mulatu T, et al. Late initiation of antenatal care among pregnant women in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia: A facility based cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:13.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tolossa T, Turi E, Fetensa G, Fekadu G, Kebede F. Association between pregnancy intention and late initiation of antenatal care among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2020;9:191.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abame DE, Abera M, Tesfay A, Yohannes Y, Ermias D, et al. Relationship between unintended pregnancy and antenatal care use during pregnancy in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. J Reprod Infertil. 2019;20:42.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.

The Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research is a monthly multidisciplinary medical journal.